What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Political ads are banned from TV and radio, but candidates and parties are free to run any ads they want online – and more are choosing videos

With the recent Dublin Bay South by-election, another public vote came and went without any regulations around online advertising.

It’s been years since issues were first raised around a lack of oversight of online political advertising, and how broadcast bans, moratoriums and limits on spending do not apply online.

While proposed bills do aim to cover political advertising, so far little has been done and what is proposed may not be enough.

And even as the government has dawdled with dealing with issues already raised, this election saw a shift in online electoral campaigns that also needs to be considered: the rise of video adverts.

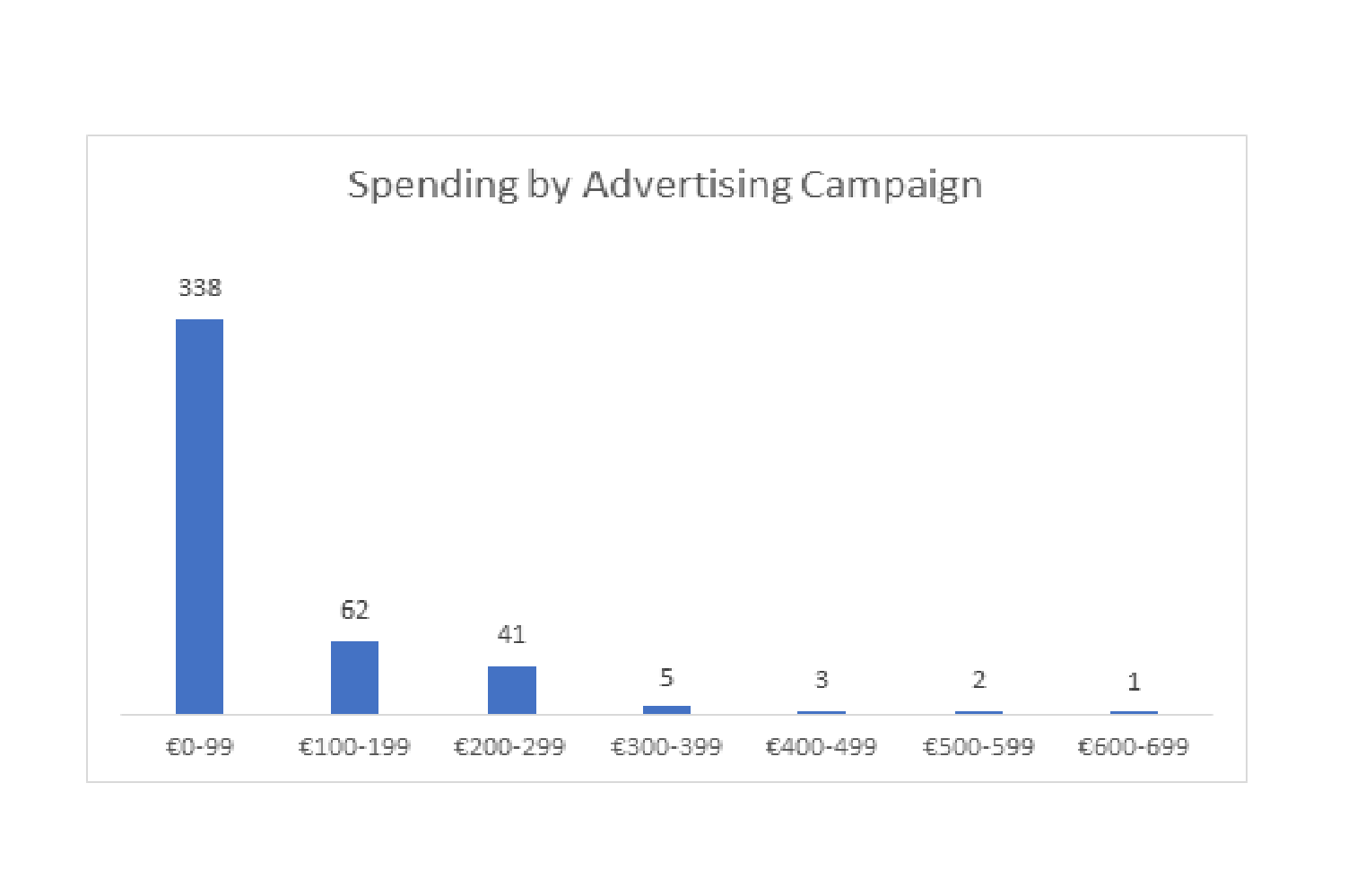

There were 452 advert campaigns about the by-election on Facebook from 1 June to polling day on 8 July, according to the Facebook Ad Library. Overall, 20 funders advertised across 24 Facebook pages.

Eight out of the 15 candidates had advertising campaigns on the platform.

As well as on Facebook, Labour’s Ivana Bacik ran 15 adverts on Google during the campaign each costing under €50, and Sinn Féin ran two: one under €50 and another between €50–€500, both about voter registration.

Candidates only have to report spending to the election regulator, the Standards in Public Office Commission (SIPO), if a payment is more than €130. Most online adverts cost less than that.

The Labour Party spent the most on a single advertising campaign: between €600–€699. Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin spent between €500–€599 on their adverts.

Alongside spending by parties and candidates, issue-based adverts ran throughout Ireland at the same time as the election campaign, which addressed candidates’ policy issues.

Several advertising campaigns by third parties promoted positions on abortion rights, environmental issues, housing and homelessness.

It is unclear the extent to which issue-based adverts shape political discourse during campaigns but they have the potential to bring issues to the fore during elections.

Most advertising campaigns ran on both Instagram and Facebook together (424) while 27 were placed only on Facebook and only one campaign was placed solely on Instagram.

The shift to including Instagram in campaigns was clear in the 2020 general election. From candidates, it demands higher-quality visual adverts. The Dublin Bay South by-election saw campaigns up production quality.

While some parties leant towards more traditional methods of promoting their candidates, with billboards and roadside placards, others such as Labour’s Ivana Bacik and People Before Profit’s Brigid Purcell also made short video adverts.

They were high-quality, stylishly shot and professionally edited, with optimistic soundtracks, and punchy graphics.

One candidate alone appears to have had a range of people supplying campaign content, including a digital campaign manager, a video producer, an artist, and five communications people.

Electoral regulation in Ireland is mostly concerned with transparency, fairness and equity among candidates.

Advertising directed towards political ends is banned on Irish television and radio.

That’s because it has always had a higher barrier to entry in terms of production and distribution costs, potentially excluding candidates with shallow pockets.

Regulation was designed to prevent the electorate getting information from only a small number of political parties that could afford to advertise. There were also concerns about whether attention-grabbing videos would diminish the quality of political debate.

These are the same concerns we face today regarding online political advertising. However, these days, in the absence of any reforms, political videos can be circulated on social media and do not fall within the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland’s remit.

The risk to the information environment during elections remains the same: a few well -resourced political actors can overwhelm the online environment with catchy content.

The advantage generally among candidates still lies with those who are established, and backed by parties, who are more likely to be able to get the resources (voluntary or not) to make impactful videos – rather than new, independent candidates.

But it’s not just candidates and parties. One rogue actor with the right team could produce multiple high-impact multimedia content in multiple campaigns, astroturf support, set political agendas, frame policy issues, undermine candidates, and disrupt political discourse without having to pay a platform.

Proposed electoral regulation should be designed in a way that would level the playing field for all, but it is not.

Neither the Electoral Reform Bill, the Digital Services Act nor the Online Social Media Regulation Bill take a broad approach to new practices in political campaigning.

They tend to be rooted in the analogue understanding of political advertising that focuses only on buyers, platforms and beneficiaries, and does not account for the complexity of how political and election campaigns are run in the hybrid media era.

So what are the options? One would be to allow video advertising across all mediums.

A 2009 Broadcasting Authority of Ireland report, authored by Professor Kevin Rafter of Dublin City University, suggested that there was value in removing the broadcast ban. It could enhance voter engagement and be possible to impose some regulatory limits to ensure a fair playing field.

The Digital News Report Ireland 2020, which surveys news consumers in Ireland, suggested that the public might be open to it, with 47 percent saying political parties should be allowed to advertise on TV.

Or, we could ban video advertising on social media. Some 53 percent of people think political parties should be barred from advertising online, according to the report. However, this is unlikely.

The Electoral Reform Bill does not distinguish and defines online political advertising as “any form of communication in a digital format … during an electoral period … for which a payment is made to the online platform”.

High-value video advertising is placed in the same category as other media without regard for the difference between production costs.

If we do allow video election adverts either on TV or online, questions remain about what we should know about them to ensure fairness and transparency in the electoral process.

Reforms need to be considered within the framework of preventing wealth from manipulating the media environment. We need to understand all of the resources and services that go into producing online advertising campaigns.

For now, online election and political advertising is largely unregulated and proposals to address the situation are limited.

Proposed legislation does not take into account the resourcing of new communication practices and is already falling behind practice.

Considering that the pace of reforms to date has been slow given the gravity of the situation, it is unlikely that meaningful regulation will be in place for the next by-election, general election or referendum.

Likely ahead, are ever more changes in the form, style and distribution of election advertising.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.