What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

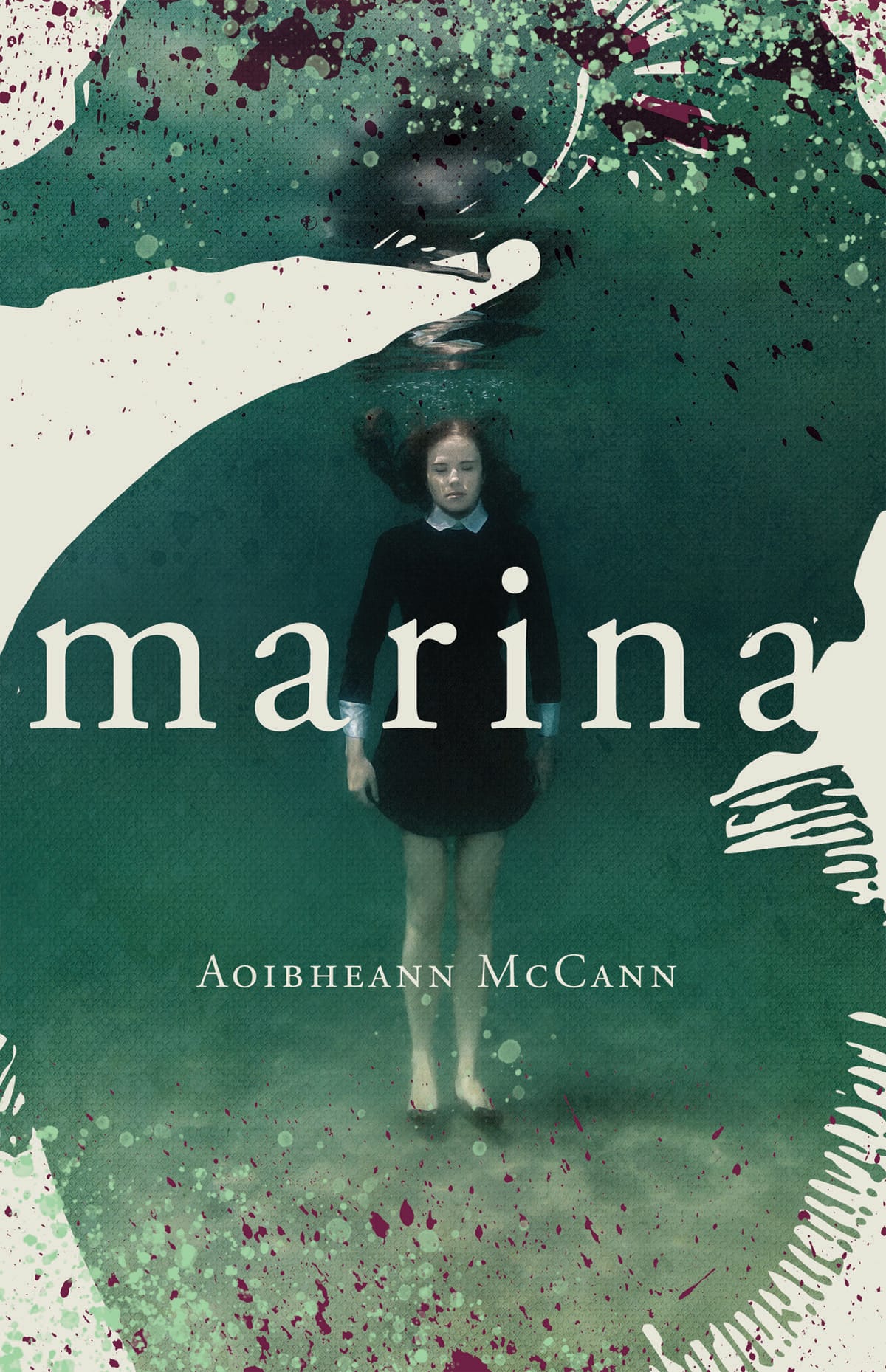

Aoibheann McCann’s novel is “sensitive and melancholic”, “a poetic tale of a life that is anything but”, writes our reviewer.

Marina belonged to the sea and not to this world of ours.

In Aoibheann McCann’s recent novel we follow the protagonist, Marina, through a heartbreaking journey as she tries to trudge into our unforgiving society. We learn of her attempts to empathize, love, and understand the people around her, and her striving to belong.

She narrates the story of her life from her first gasp of breath until the present day, when her twenty-something self is sitting in a dull room with somebody who seems to be her psychiatrist.

This narrative, entirely in first person, is vivid. She talks of growing up in a small town in Ireland with her parents and two sisters. She describes how her mother took her to a small room where a lady made her colour onto papers and she heard the word “autistic” for the first time.

She talks about the time when Mona, a teacher from school, brought out Marina’s genius at playing the piano. The story details how she found her first friend in Jamie, Mona’s son, and how Marina, as a teenager, went on to a sea of another kind, London, to pursue her talents and met Jules, the boy who stole her heart.

It’s a poetic tale of a life that is anything but. The persistent melancholic strain in the narrator’s voice holds throughout.

There is a tenderness in Aoibheann McCann’s writing, which ripples through to bring out the protagonist’s tenderness. Some lines are beautiful, the kind you want to read over and over. “The flooding seas are coming to take me back to where I should be,” Marina tells her shrink at one point.

“In the beginning was Hippocampus, and cells surrounded it, stuck to it, wanting to belong, and the brain was built clamouring for appendages. It explored the land and soon grew bored,” she says, when she talks of memories of her earlier life.

Marina’s breezy thoughts, though well-articulated, do ramble at times. The author plays on recurring metaphors; sometimes they feel too repetitive, but usually they add to the narrative.

It was the portrait of the unnamed small town in Ireland that was most endearing to me.

The tales of how as Marina’s sisters Rachel and Fionnuala grew up, how they frequented the same few pubs and married similar neighbourhood boys. The overt alcoholism of George Christopher, Mona’s husband. The devout Catholic families who never missed Sunday mass.

The most important events of the town were funerals or weddings, and they usually alternated one after the other. It is a portrait of a town in which everyone not only knew everyone else, but everyone spoke about every other person.

Later when Marina moves to London, the bustle of the metropolis takes the teenager by surprise. There, she experiences love and trauma. It is well juxtaposed with life in her small hometown.

Running through the book is also another character and motif: the sea and looming environmental disaster.

The climate is changing. The world is becoming hotter. Humans are driving this ecological imbalance. Industrial waste and oil spills have polluted swathes of the ocean. We have all seen pictures of seabirds drenched in oil, struggling to flap their wings. What once was their home and means of sustenance is now our dumping ground.

The sea is rising, and will rise to consume a large part what is “our land”. Marina knows this, and she is pained by it.

In one conversation with her psychiatrist, Dr O’Hara, Marina expresses her anxiety metaphorically. She describes her innermost thoughts and compares them to those of the sea:

“I imagine this; sun hot, full face, arms upstretched, growing closer and closer to worship, sleeping only to want for its return, glory in the rain, sliding within, water loving me, helping me reach higher and higher, till the day the sun fades and loses interest in me and I fade and melt, pecked by birds, oozing oil into their blood.”

Marina and Jules are shown to care about the environment and try their best to cut their carbon footprint. This concern fuses with Marina’s personal attachment to the sea.

Bringing in large themes, such as climate change, is ambitious. Yet it is expressed subtly and though, at times, it feels disconnected to the main narrative of the book, it did remind me of Indian author Amitav Ghosh’s ideas around how modern writers of fiction usually shy away from writing about climate change. Why does climate change cast a much smaller shadow on literature than it does on the world?

I have often taken the DART to Dún Laoghaire just to walk all the way up to the edge of the pier and stare out into the sea. The water looks different each time. Below grey October clouds. Below sunny August mornings. Or maybe it was me that was different.

I wonder what a pregnant Marina saw when she peered into the grey of the sea below that pier. I wonder if she saw the same colours that I did. If she saw her reflection in it and found the deep longing that she had for the sea. Maybe she looked for the answers to her troubles in the grey depths. Finding nothing, she had to part with it and go back to the world to live her life.

Marina is a sensitive and melancholic tale. I wouldn’t read this on a breezy Saturday afternoon on a train or in the park. It’s slow and repetitive in parts. It’s worth lingering over, dwelling on the motifs. I’d rather reach out to this book on a pensive Tuesday evening when I find myself asking questions that are part existential and part rhetorical.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.