What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Dr Joseph Chamney Ridgway who served in the British Army – including as a medical officer in Uganda – was staying at the Shelbourne Hotel over Easter 1916

Forty years after the 1916 Easter Rising, Dr Joseph Chamney Ridgway had almost forgotten about his tiny part in it.

“Until I was reminded in the course of a conversation with a learned and esteemed colleague,” he wrote in a witness statement dated 4 June 1956.

Ridgway – the son of corn and butter merchants in Waterford – had studied medicine at Trinity College Dublin and graduated in 1910. He enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1915.

His witness statement – his account of a few days around the Easter Rising and his encounter with the wounded James Connolly, who he helped correspond with his wife – is kept in the Bureau of Military History at the Military Archives in Rathmines.

Sixty-four years after his death, Lucy Smyth, a former Dubliner in London with a penchant for the forgotten past, stumbled upon more fragments from the doctor’s life.

She recently bought some of his belongings, listed for £30 on the website of an online auction house based in the United Kingdom.

There’s nothing in the stash about Ridgway’s time treating Connolly.

But it does include black and white photographs of people, yellowed postcards, and a letter he wrote in 1912 during his time as a medical officer in Uganda, a British colony at the time, which reveals his interest in discovering new ways of treating his patients’ wounds.

Smyth is donating these to the Military Archives to be put on display, she says.

Lorcan Collins, a historian and a James Connolly biographer, says Ridgway deserves to be remembered. Many joined the British Army to survive at the time, he says.

“His kindness to James Connolly in asking him if there was anything that could be done for him – well, that should not be forgotten,” said Collins.

Fin Dwyer, another historian, said that when remembering Irish men in the British Army, maybe the point isn’t whether someone is good or not.

It’s about understanding the bigger picture, he says. “And what was happening in terms of how the British empire functioned.”

Ridgway’s witness statement, already in the archives, mentions how, in the spring of 1916, he was in Dublin and staying in the Shelbourne Hotel on the north side of Stephen’s Green.

The day after Easter Monday, he was summoned to Dublin Castle, where he found himself dressing the wounds of a jailed James Connolly.

While caring for Connolly, Ridgway asked if he could help with anything in a small way, to which Connolly responded that he wanted to get a message to his wife.

Ridgway helped them correspond. “Aided by one of the V.A.D [Voluntary Aid Detachment] ladies who were giving their services to this Red Cross hospital,” says his statement.

Ridgway died in 1959 in Co. Wicklow and is buried in his home county of Waterford.

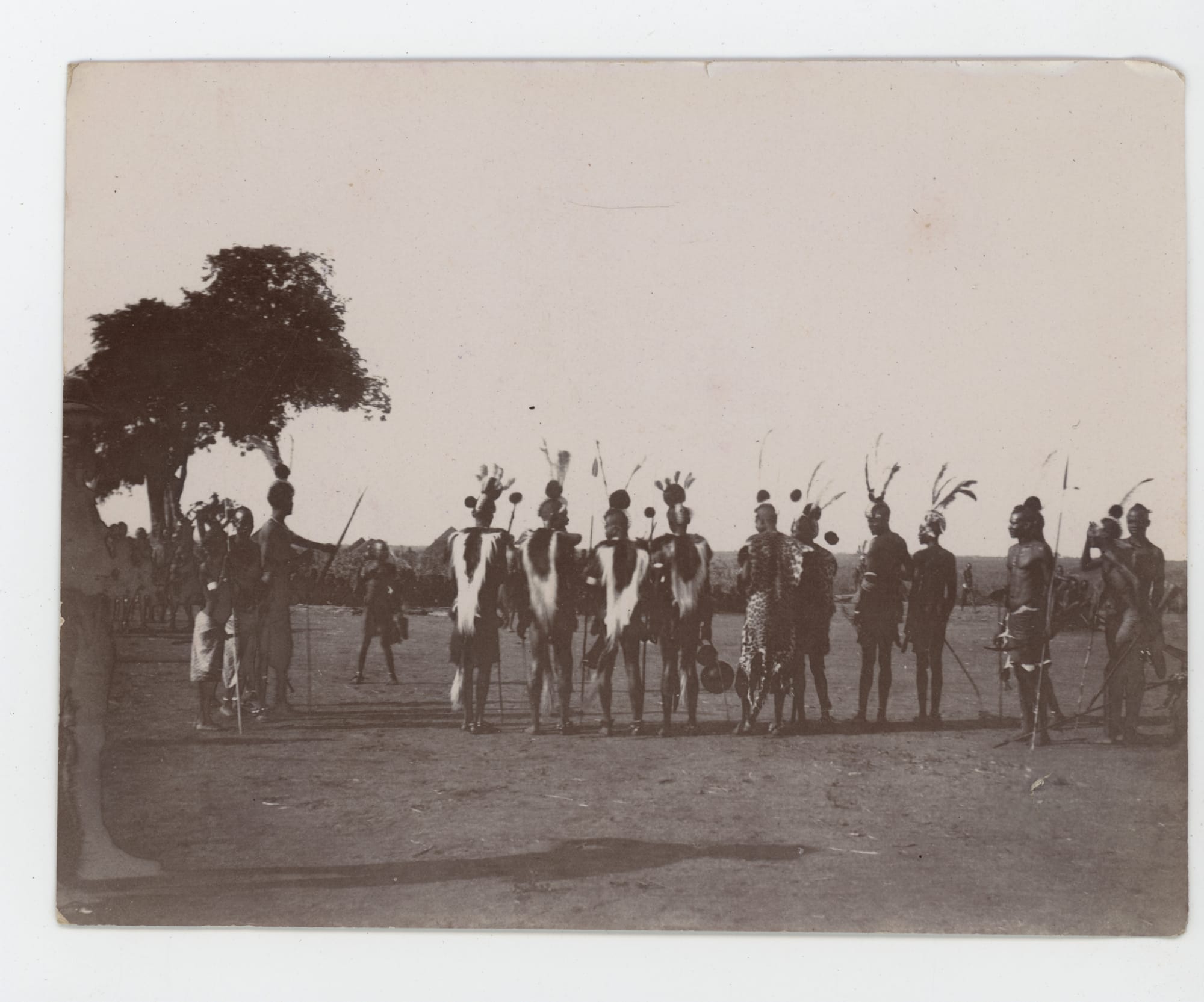

But his auctioned belongings hint at how far he travelled as a medical officer in the British Army. Among them are black and white photographs from his time in Uganda.

Uganda became a protectorate of the British Empire in 1894. The country won independence in 1962.

One of Ridgway’s photographs from Uganda shows a Black man in traditional attire walking ahead of a crowd next to a White man in a hat and a long coat whose right hand is resting on his chest. Someone in the crowd is carrying a Union Jack.

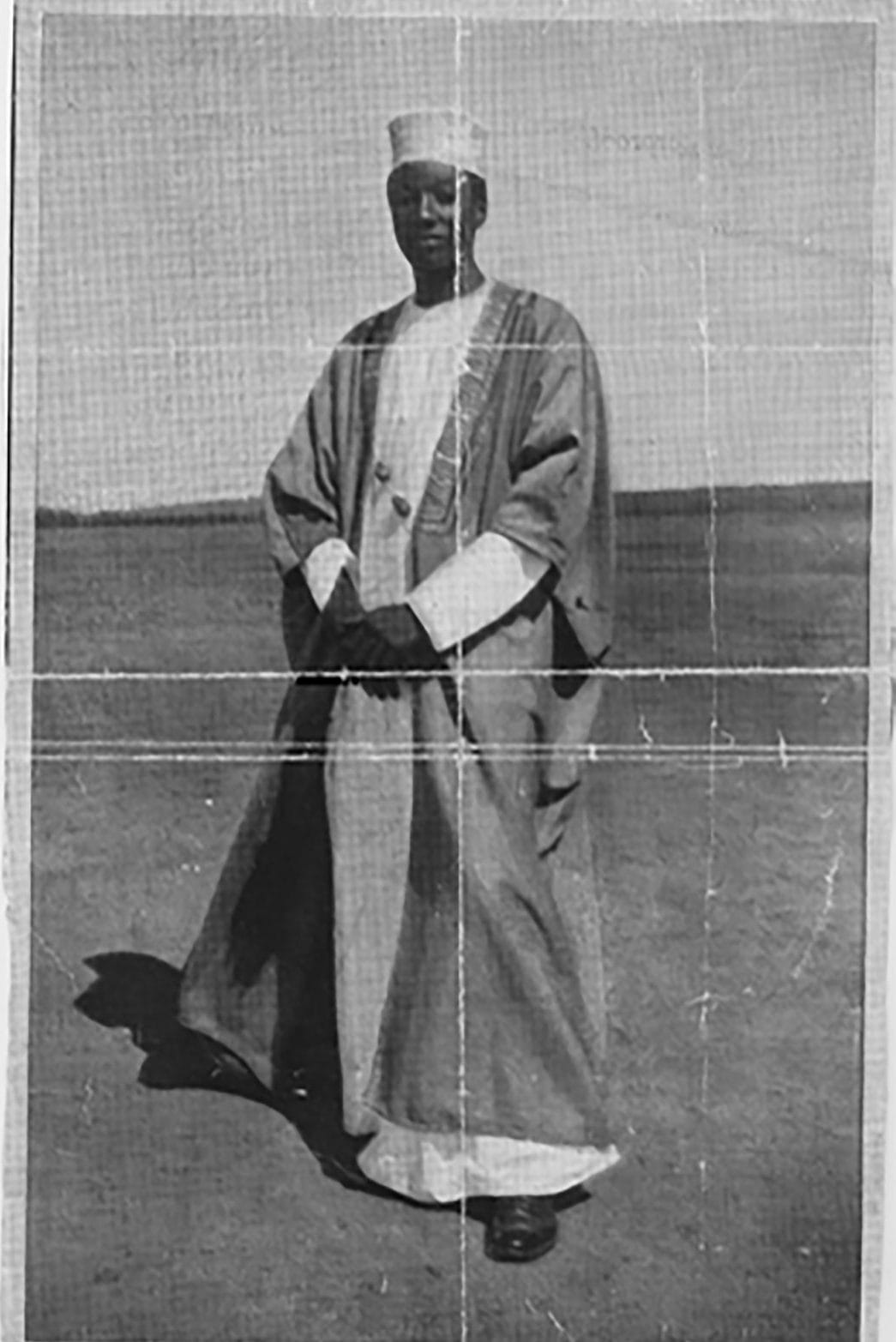

“The King of Uganda and his excellency Frederick John Jackson, Governor of Uganda, 1911,” reads a scribble on the back of the photo. There’s a solo portrait of the king, Daudi Chewa II, too.

That was the same year of what has been called the Lamogi Rebellion in northern Uganda, a rebellion against a policy of weapons confiscation.

At the top of a letter dated 1912, seemingly to a journal, Ridgway places himself in the north, in Nimule in Nile Province. He relays the usefulness of a type of iodine solution as an antiseptic when treating gunshot and other wounds.

Ridgway recounts the story of a patient who turned up to his hut after a crocodile bit him. “He had been down to the Nile close by to cut grass for his employer an Arab trader,” it says.

The man made a lucky escape, the letter says, before detailing the nature of his wound and how the doctor washed it with the iodine solution for 15 minutes and saw the “native” man regularly after.

Ridgway later talks of how he went along on a “punitive expedition” as medical officer “into the hinterland of the Nile, against some hostile tribes”. He doesn’t give more details of where exactly or how he felt about it.

He treated more than 100 cases of gunshot wounds, spear and arrow wounds, and cuts, on both sides, he wrote, using iodine as an antiseptic.

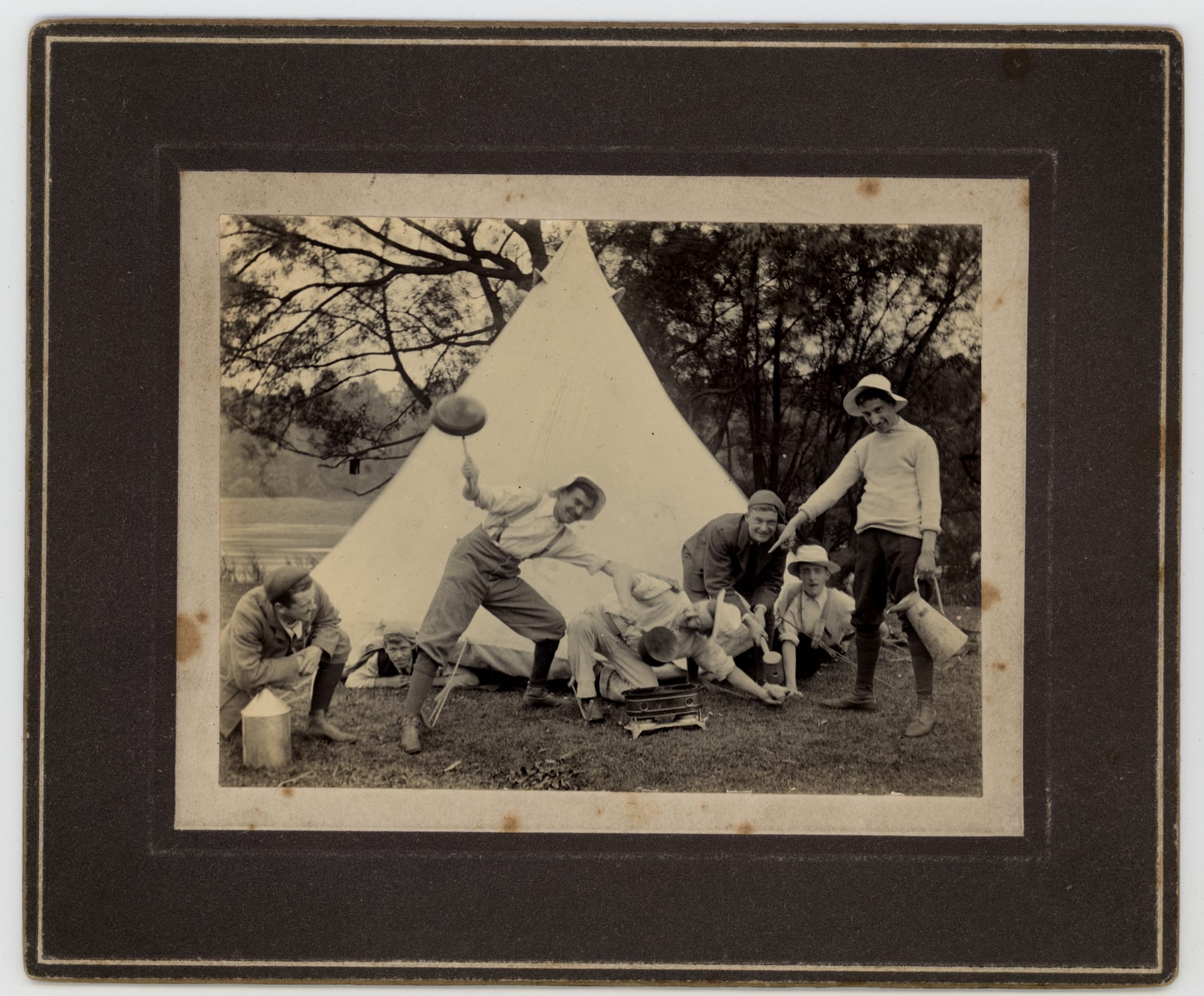

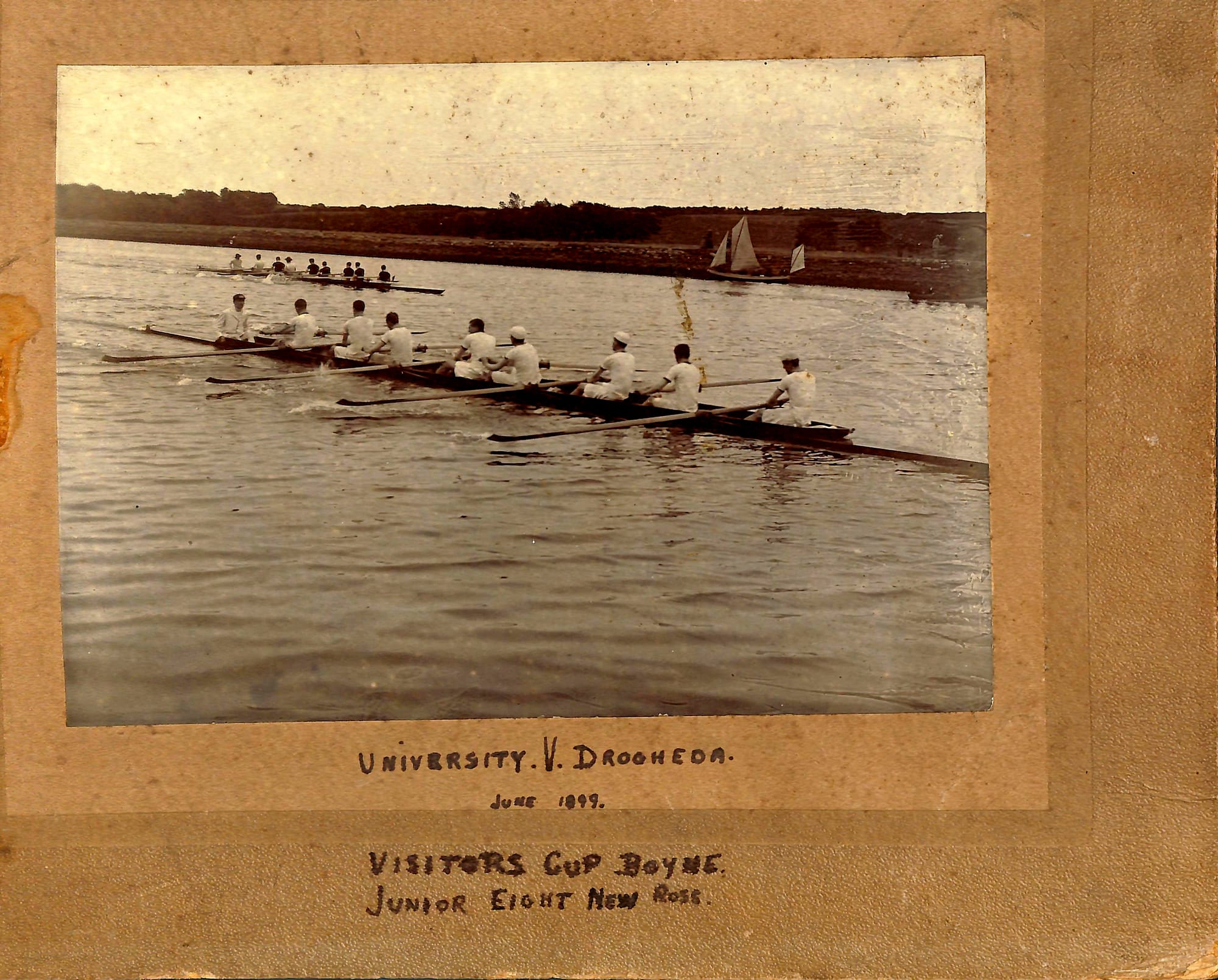

There are traces of his personal life. Photos of men smiling and camping, his graduation in Trinity, and a university rowing race with the Drogheda team. One portrait shows Ridgway in a suit, cuddling with a small dog.

The collection also has several personal statements about his character and professionalism that read as if they were done for job applications.

By 1916, Ridgway was back in Ireland. In his witness statement in the Rathmines archives, he remembers Easter Monday of 1916 as a day that came in bright and sunny.

He’d been invited to join a party headed to the Fairyhouse horse races in Co. Meath. Gorse was in bloom, birds in the trees, he writes.

Just before the final race, a British officer told him there had been a “rebellion” in Dublin. “He warned me to be watchful on the way home,” wrote Ridgway.

Back at the Shelbourne Hotel, soldiers had set up a machine gun in the front hall, says the statement.

Ridgway was summoned for duty the next day and told to take charge of wounded prisoners in a large ward. “And also to act as a special dresser for an important political prisoner who was in a small room by himself.”

It turned out to be James Connolly.

“I saw in bed, a medium sized, stoutly built, bald, florid complexioned middle aged man with a bushy moustache,” he wrote.

Ridgway’s statement details Connolly’s bullet wound. “He had sustained a bullet wound on the right leg causing a compound fracture of the two long bones.”

He prepped Connolly for surgery, it says, and “Mr Kennedy of Merrion Square and the late Colonel Tobin” operated on his injured leg.

After the operation, Ridgway dressed the wound twice daily and they chatted. “So I naturally got attached to my patient,” he wrote.

One afternoon, the statement says, Ridgway was the doctor on call in the casualty room when a soldier handed over a telegram signed off by then Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith.

It said: “Officer Commanding Dublin Castle. The execution of James Connolly is postponed.”

Ridgway writes that he put the telegram in the left-hand top pocket of his tunic and went for tea. When he showed it to an officer on duty, the soldier looked alarmed and asked if he’d told anyone about its content, which he hadn’t.

It was said, he writes, that when General John Maxwell, the commander in charge of British troops, read the telegram, he had said that he would resign then and there if any political prisoner were granted a reprieve.

“As this would have caused a sensation at that critical stage of the Great War his wish was granted,” wrote Ridgway.

Ridgway sensed that “events might occur in connection with the medical duties, which might be unpleasant,” he wrote.

So he got permission to rejoin his unit and walked “gladly out into the sunshine of a glorious spring morning”.

Collins, the James Connolly biographer, says it’s easy to lose nuance and look at the past through a binary of good and bad.

“For many years in Ireland, we were inclined to be quite black and white regarding Irishmen who fought in the British Army during World War One,” he said in a text message.

He’s proud of his grandparents, who were in the Irish Republican Army and Cumann na mBan, Collins says. “However, I have a Great Uncle who died in Ypres serving the British.”

Some Irish men joined the British army to afford food or rent in Dublin, he says. “Separation allowance more or less covered the rent of a room in the Tenements of Dublin.”

Others joined hoping to curry favour with the English, he says. “The Irish were one of the largest ethnic groups in the British Army pre-War so there was a long tradition of Irishmen in that uniform.”

At 14, James Connolly himself had joined. That shouldn’t be forgotten when judging others, Collins says. “He said he joined for the want of something to eat […] conscription by starvation as he called it.”

Dwyer said that, when remembering Irish men in the British Army, understanding the bigger picture is what is important.

Ireland was just another colony in the British empire, he says. “Regiments were drawn from huge numbers of people all across pretty much all the colonies of the British empire.”

The British government used those regiments to subjugate other parts of its empire. That’s how its machine thrived, he says.

Some people did ideologically side with the government in London and joined its army because of that, he says.

But many young men didn’t have many options, and the allure of a better shot in life and even sometimes the opportunity to travel the world drew them in, says Dwyer. “And in the 19th century, the number of people who’d served was pretty high.”

But attitudes shifted, he says. Irish men who fought with the British at the start of World War I, he says, came back in 1916 to a changed Ireland, where support for the army had started to sag.

And “the threat to introduce conscription in Ireland alienated the army further from the wider population”, Dwyer says.

There’s no candy-coating the violence and cruelties inflicted anywhere by those who worked for the British empire, he says.

But “I don’t like the idea of reducing it down to the moral failing of one person”, says Dwyer. Rather, he says, we should understand the process.

Collins, the James Connolly biographer, says that Ireland is becoming better at understanding Irish men who fought under the Union Jack those days.

He says Ridgway’s kindness towards Connolly should be appreciated.

But he draws the line somewhere. He will never wear the poppy, he says. “As that commemorates more modern British Army veterans such as the Paratroopers who murdered people in Derry in 1972,” said Collins.

Smyth, the woman who bought Ridgway’s belongings, said in an email to the Military Archives on 11 August that she looks forward to his papers returning home.

“Dr. Ridgway was an Irish man,” she wrote. “This feels right.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.