What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

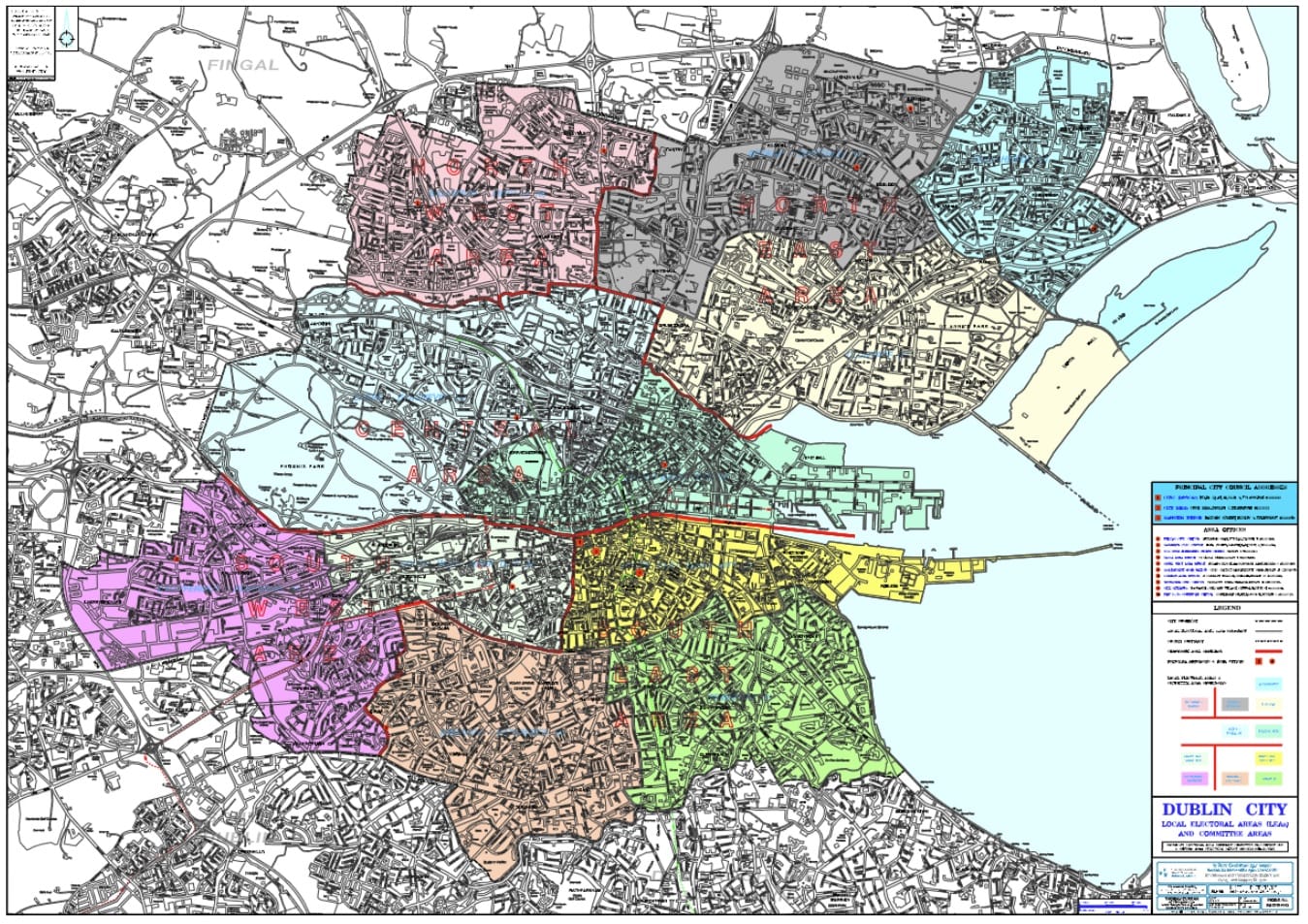

Meanwhile, the council’s North West Area is set to get just 4.4 percent of these development levies.

On a sunny Tuesday morning in Merrion Square, a young couple stroll as they listen to music on shared headphones. A grey squirrel hops past them and up a tree.

The park is an oasis of green in the south inner-city, adorned by trees, picnic benches and sculptures.

This year and next, Dublin City Council plans to add to the park. It earmarked €3.4m to build tearooms here, paid for by development levies – the payments made by developers when they build something – in its capital programme for 2022 to 2024.

The council plans to build six tearooms or visitor facilities in parks across the city, mostly funded by the development levies. But they’re not evenly spread around.

Three of those parks are in the South East Area, and only one – at Blessington Street Basin – is on the northside in the Central Area. None are in the North West Area or the North Central Area.

That spread of funding mirrors how development levies as a whole were allocated in the capital programme – with the most money from this particular funding pot going to the South East Area, the wealthiest corner of the city.

A report issued last week to councillors on the finance committee says that, between 2022 and 2024, the council expects that around €70 million in development levies will be spent in the South East Area.

Meanwhile, €34 million will go into the Central Area, and €24 million to the South Central Area.

Working down the list, €14 million is expected to be spent in the North Central Area, and just €10 million will go on projects in the North West Area. Around €68 million has been allocated to citywide projects.

Development levies are just one of the funding streams for capital projects – basically, infrastructure projects – in the city. The council can also use its own funds, grants from central government, or loans, for example.

But while they only account for 9.3 percent of the budget for capital projects listed in the council’s programme for 2022 to 2024, they cover more than 35 percent of the capital spend on culture, recreation and amenity, and more than 20 percent for road safety and transportation.

Sinn Féin Councillor Séamas McGrattan, who chairs the council’s finance committee, says that to get a clear picture of capital spending plans it’s important to look at the overall spending in the capital programme, not just to focus on spending from development levies.

“I took it from the report that we are spending more in other areas from different budgets,” said McGrattan, who represents the Central Area.

Its tricky to categorise, and so analyse, all of the streams of funding allocated for culture and recreational capital projects as some big projects – like the Parnell Square Cultural Quarter – could be counted as citywide developments, or area-specific ones.

But a tally of the figures does suggest that the North-West area is bottom of the pack for cultural and recreational funding even when all the funding streams are included.

Dublin City Council didn’t respond to queries about whether the allocation of the development levies was fair.

The report to councillors on the finance committee was prompted by a wider debate among councillors as to how development levies should be allocated across the city.

Labour Councillor Dermot Lacey – who asked for the report – has been pressing for some of the money paid by a developer in levies for a particular site to be spent near where the construction is happening.

That way, people can see some benefit, he says. Even if it’s just something like 5 percent of the funds, says Lacey.

Projects funded by development levies generally move faster than those funded by, say central government grants, says Lacey. Grants, outside of the council’s control, are riskier, he says.

He would like to see the entire funding process for local authorities in Ireland reviewed, he says.

Prescribing that a portion be spent near to development though is something that council officials have spoken against.

At a full council meeting last December, Máire Igoe, an acting executive manager at the council, warned of possible side effects if funding were ringfenced.

It could disadvantage areas that councillors may be most wanting to help, she said, if particular areas are able to generate more development in levies than others.

At the meeting of the finance committee on 19 January, the council finance manager Kathy Quinn said that the council aims “to target areas with lower public assets”, in spending development levies.

“The central tenet is that the funds are required because there is a deficit in a class of public asset … which must be addressed to improve quality of life,” says her report to councillors.

“The application of development contribution funds then must be in line with such public asset deficits and not in line with geography,” it says.

In the January meeting, councillors touched briefly on the figures.

Social Democrats Councillor Mary Callaghan asked why only 4 percent of the planned spending was in her area. “Am I reading that right that we are losing out in the North West?”

The report says that in 2021, 12 percent of the levies collected were from development projects in the North West Area, but the council plans to spend 4 percent of the revenue from levies there from 2022 to 2024.

Quinn said that each area also contributes to the funds for the citywide projects that benefit the whole city.

Green Party Councillor Donna Cooney, who represents the North Central Area, said the levies should be spent where they are most needed.

The council has announced plans for a tearoom in Fairview Park, but the project does not appear in the capital programme.

“The reply I got is that it was still going ahead but they didn’t have the funding for it,” says Cooney. “That tearoom has to go ahead.”

A council report issued last June says that the detailed design work is set to begin in 2023.

The North Central Area does have a shortage of community and recreational infrastructure.

A cultural infrastructure audit, drawn up as part of the process for the current city development plans, found that large swathes of the northside don’t have any cultural buildings apart from libraries.

Kilmore West has no playgrounds and councillors have been told that there is no funding forthose.

But Lacey, who represents the South East Area, says that he doesn’t think his area is getting more than its fair share of development levies.

The report only captures a moment in time, he says, so a few big projects can skew the percentages. In the past the north inner-city got a massive amount of investment, he says.

Some parts, like the Docklands, are undergoing major development and so they do require extra infrastructure spending, he says.

He wonders if the spend on the tearooms in Merrion Square should be counted as a South East Area project or a citywide project, since it will mainly benefit the city centre and tourists, he says. “What do you define that as?”

At the meeting, Labour Councillor Mary Freehill also defended the South East Area’s allocation.

“Rathmines in terms of community wealth is probably the poorest in the entire city,” she said. “We don’t even have a community centre.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.