What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

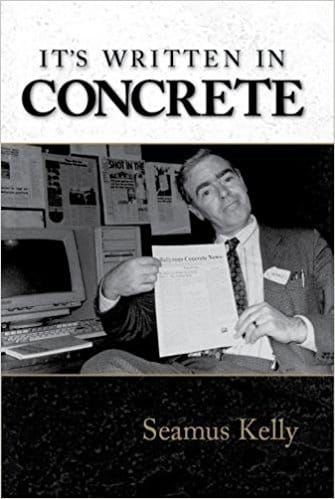

In his memoir, Seamus Kelly – founder of the Ballymun Concrete News – sets about convincing journalists and publishers of the need for positive news. It’s a hard sell, right now.

In the mid-1990s, Seamus Kelly decided he wanted to counter the hard negative news coverage of Ballymun.

Media focus on crime and anti-social behaviour in the suburb stigmatised the area and hurt residents, he writes, in his memoir It’s Written in Concrete.

That wasn’t the Ballymun he saw. It was a neighbourhood of “concrete people who organised themselves and arranged the facilities and amenities that no one else would”.

Out of that dichotomy grew his idea for a different approach to news, one that was unabashedly positive, and one that he gave life to through the hyperlocal newspaper he founded, Ballymun Concrete News.

The newspaper wound up in 2006. But Kelly is still hawking the spirit of the publication. Journalists and editors should take heed and turn their keyboards to more uplifting tales, he writes.

Could that approach save newspapers in crisis, faced with declining circulations? The idea of ignoring stories like the Cervical Check scandal, the smearing of whistleblower Maurice McCabe, soaring homelessness and a city that’s pricing out its residents, and instead looking for more positive things to write about may seem strange.

But surely there are lessons to be learned from Kelly’s hard-won experience from his years running the Ballymun Concrete News.

Daily headlines still depress Kelly. Surveys suggest he is right in thinking he is not alone.

Almost 60 percent of respondents in Ireland to last year’s Digital News Report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism said that they avoid the news sometimes.

Most of those complained that it had a negative impact on their mood. The number two reason was feeling unable to do anything about what they read, anyway.

Kelly’s solution to this is a focus on positive stories, as he did with the Ballymun Concrete News and during his career as a freelancer.

To wit: the tale of a model, told she would never walk again, who made a full recovery. Another popular piece was the story of an incontinent and nappy-wearing terrier, Sparky, who lost his hind legs and – here comes the good-news bit – was wheeled around by a loving carer.

In many cases, good-news stories can favour the status quo. Newspapers have stretched, or small, resources. Working out how to allocate those week to week is a constant struggle. How can you justify writing the heart-warmer?

Kelly seems to square that circle by adding some nuance to his definition of “positive news”. It can include exposure of political corruption, white-collar crime, or dysfunction in the health service, he says.

That’s because it “wakes up” institutions, and “encourages empathy toward innocent people hanging on by a thread”, he writes.

You could argue that this comes out of the blue, that Kelly is stretching his definition a bit too far. Why not just say there’s a space for watchdog journalism too?

Kelly writes that he believes local and national newspapers have no concept of positive news. But he’s not as alone as he might think.

There are heaps of people around the world who have caught on to concerns that a focus on problems, without solutions, might leave readers feeling disempowered.

Take, for example, the Solutions Journalism Network, where reporters gather to share stories that look beyond what’s going wrong, to focus on what might fix it.

It’s not about a search for silver bullets or glorifying an individual’s quest. It’s more wonky looks at how policies are playing out in practice.

Advocates argue that, done well, it can lead readers to engage more, to read for longer, and help build more trust in a publication. There’s also some evidence it can compete with negative headlines, research suggests.

Kelly wasn’t exactly doing solutions journalism, but the impulse seems similar.

He was switched on to the welfare of his readers. Residents in Ballymun read only negative stories about their communities. They struggled to gets jobs because of the addresses on their CVs, he reminds us.

Some have pointed to the way in which the perpetually negative stories told about Ballymun made it easier to hype the regeneration of the area.

The “preexisting negative reputation was a very powerful tool for persuading people that the way they had been living was wrong, and unsustainable, and needed to be changed in a very fundamental way”, said Turlough Kelly, the film-maker behind the documentary The 4th Act, last year.

More recently, Gerry Fay, a community leader in North Wall, has said he worries that something similar has been at play in the Docklands, and news coverage of the North-East Inner City. Talk down an area, and it’s easier to tear it down.

But talking up an area also has obvious shortcomings – if it means ignoring problems. You wonder at times if Kelly veered a little too far in that direction.

He writes that he saw his role in coverage of the regeneration as helping the area attract outside investment. “If the Ballymun Concrete News could possibly facilitate this, I knew I was doing the right thing,” he says.

“I was very committed to covering whatever companies would invest in the community and what employment opportunities they would provide,” he writes.

It was also to keep residents distracted from the ongoing construction. “Building works surrounding your homes on almost a daily basis can be very demoralising,” he says.

You wonder how much was missed by this focus on positive coverage, and whether a deeper and more nuanced look at the regeneration might have served the community better, and been more reflective of how the regeneration was experienced.

Kelly’s book doesn’t dwell on his paper’s role as an independent outlet. But whether you subscribe to his call for positive coverage or not, the Ballymun Concrete News did illustrate the importance of diversity in media ownership and editorial mission.

These days, Kelly keeps the spirit of the Ballymun Concrete News alive through Facebook pages like this one. But it doesn’t attract many new readers, he says.

Like many smaller publications, the independent-publishers/”>shrinking reach of his Facebook posts means he would have to pay to boost them to reach more readers. “This costs money and this is a voluntary news page,” he says.

Sunday Times editor John Burns recently suggested that the demise of the Ballymun Concrete News might be evidence that Kelly’s pitch is misguided – and that the publication might have survived had been less Pollyanna in approach.

But the lesson from Kelly’s memoir as I read it is that, whether or not people read the Ballymun Concrete News, whether or not they wanted it, was tangential to its demise or survival. It was funded by advertisers, and the much-needed advertising didn’t come.

As the newspaper’s circulation grew to 20,000 copies a month – a staggering print run for a hyperlocal – Kelly gambled on the future.

He saw the planned regeneration of Ballymun Shopping Centre as the answer to any funding problems: builders, developers, and planners would bring new advertising. He took out loans and an overdraft to tide him over until this ad revenue came rolling in.

But that never happened. The shopping-centre vision collapsed. Kelly was crippled by debt, and understandably heartbroken.

Ballymun, which now has an emptied and derelict shipping centre in its core and no concrete vision for its future, lost its hyperlocal newspaper, too.

Perhaps one of the reasons that Kelly set himself such a different editorial mission was because his background differs so much from many newspaper editors’.

By 10 years old, Kelly was working before school, delivering milk with the milkman in Cabra West in the early mornings. At 14 years old, he left school and got a job delivering meat for a butchers shop – until he fed some to local dogs and was fired.

He later worked as a runner, collecting copy from journalists out reporting and, and cycling it over to the newsrooms of the biggest newspapers of the day.

Other jobs followed: apprentice glazier, shunter on the railway, and a job in a hospital looking after young people with addiction problems, he writes.

It was after developing agoraphobia, though, which kept him inside for eight years, that he really started to write. At first, it was poetry and songs.

With help from his wife, children, and a dog called Sam, he started to venture out more. The family made the move to Ballymun, and – at a men’s-network centre – Kelly learnt about computers and printers and soon created his first newsletter.

When publishing the newspaper, he lived in the towers, where he and his wife would work through the night folding and creasing and stapling pages themselves to save money.

He was involved in community groups, alongside those he covered – and that closeness and conscientiousness, too, created a different kind of publication.

“If the Ballymun Concrete News achieved anything, it was to take issue with the prejudiced view of an estate whose people had, over many decades, shown an extraordinary resilience,” he writes. “Even if the ‘status quo’ was to write them off.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.