What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

The team behind the “AMEND: Unleading Water” project are helping people across the city get their water tested.

“I wouldn’t drink the water, some days it’s brown, some days it’s a normal colour,” says Donna Wilson, a resident of Dolphin House.

At the Dolphin House Community Centre at around 5.30pm on 8 July, the chat among local residents was about poor maintenance, eroded pipes, and the age of the social housing complex around them.

The estate is nearly 70 years old, says Debbie Mulhall, a community development worker. “My grandmother came to live here in the 1950’s.”

The age of the complex is one reason why on this Monday evening, researchers dropped by to talk about their project looking at lead in domestic drinking water in the city – and to invite them to get involved.

Also, there are uncertainties about the complex’s redevelopment, and it is the largest remaining social housing complex in the country, said Jeremy Auerbach, an assistant professor at University College Dublin and the team lead for the “AMEND: Unleading Water” project.

Scientists on the project have also been working with members of public participation networks (PPNs), TidyTowns groups, and other social housing residents, he said.

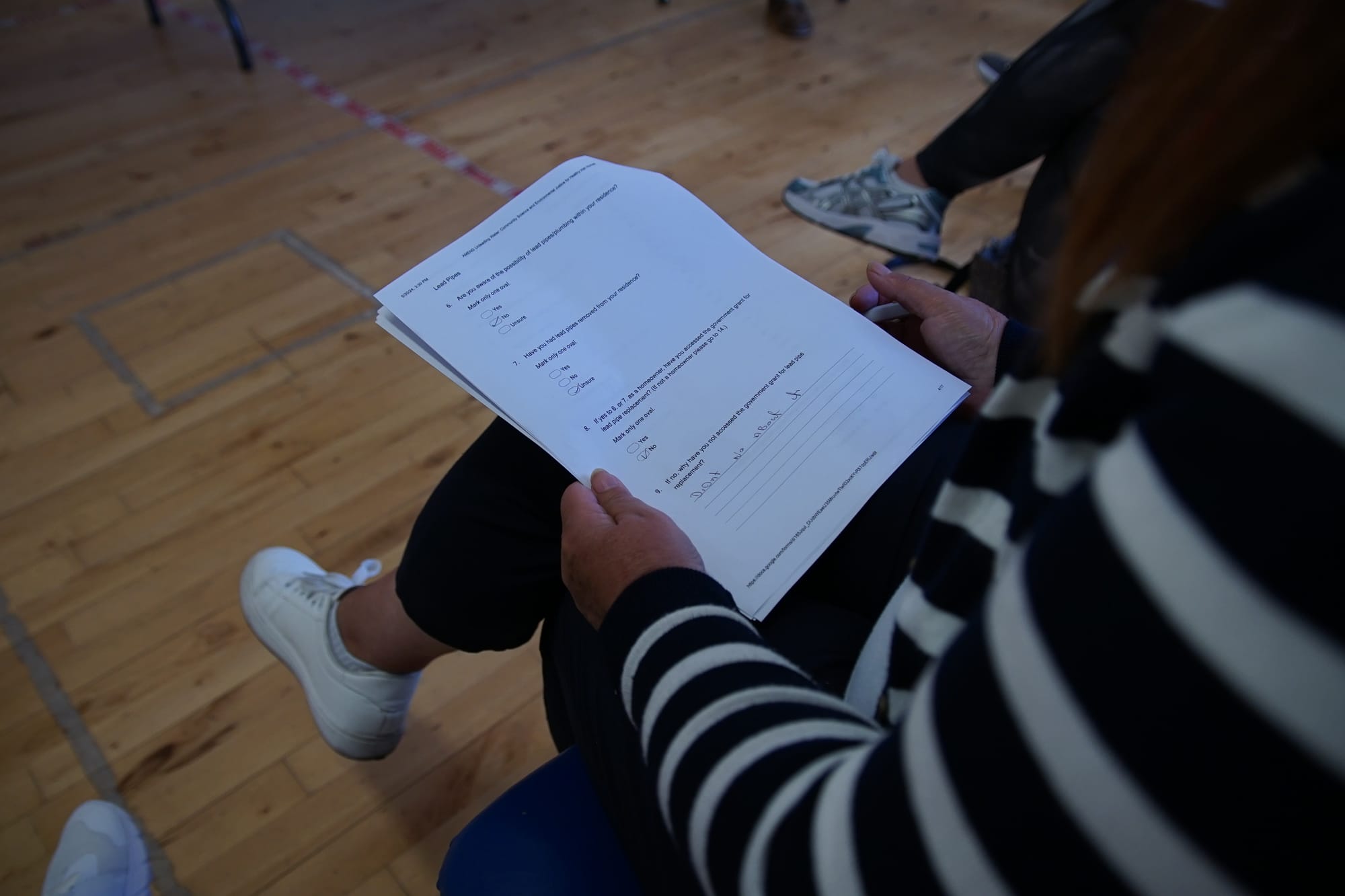

People can gather a water sample and they will get it tested, Auerbach told those gathered. “We will send it to the lab. No cost, we got money from the government.”

“We are scientists, not policymakers. Our job is not to directly influence policy, but to collect information,” said Auerbach, later after the meeting.

But he hopes all the testing will show up hot spots in the domestic water supply, he says, and that communities can use what they learn to demand change.

Nine residents turned up to hear about the “AMEND: Unleading Water” project, which is funded by Science Foundation Ireland.

Lead in drinking water is a health hazard, with lifelong consequences, especially for young children, said the survey brief given to the participants before the start of the meeting. There is no safe level of exposure to lead, it says.

But despite this, there is still a network of residential lead pipes across Ireland, including an estimated 180,000 lead pipe homes connections, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Researchers plan to start to test the water samples they have gathered in about a month, said Auerbach.

They are collecting samples taken in homes throughout a day, and that should allow them to gauge the lead levels, he said. And, they should be enough to prompt Irish Water to do any needed follow-up testing, said Auerbach.

They’ll publish results on their to-be-launched website, he said.

Irish Water have been aware of issues around lead pipes for decades but they are slow and they only cover the public network, says Auerbach. Issues on private property, and social housing, are not part of their scope but down to property owners, he says.

Irish Water does spot sampling of water, not just for lead, says Auerbach. And, if an issue is flagged in one home, they also check neighbours, he says.

Councils do provide a Domestic Lead Remediation Grant to replace lead pipes, covering 100 percent of qualifying work, up to €5,000. As long as the cost of works is more than €750.

To apply, the person must live in the property or, if it is a rental, have the owner’s permission to get the work done.

Private holiday homes, and short-term lets, or council homes, and those owned by approved housing bodies, don’t qualify for the grant.

At the meeting on 8 July, Auerbach pointed to some issues with the bureaucracy around the grant.

“They have to find a plumber, pay upfront,” he says – and of course, contact the council, get sign-off on costs from a plumber, and it’s likely to cost more than the grant covers.

It can also be problematic for renters to ask the landlord to replace the pipes, says Auerbach.

Renters may have to move out, and with the housing crisis, finding another place is tough, he said. It could also be an excuse for a landlord to evict, replace pipes, and then raise the rent, says Auerbach.

Dublin City Council approved 37 applications in 2023, and 54 in 2024, for the Domestic Lead Remediation Grant Scene, show figures sent by the council press office.

Irish Water doesn’t have the breakdown of figures for Dublin as to how much lead piping it has replaced in 2022 and 2023, under its Lead Pipe Replacement Scheme, says the spokesperson on 16 July.

“Water leaving Uisce Éireann’s treatment plants is lead free and our records show that there are no lead public water mains in Ireland,”says the spokesperson.

It is currently working on replacing all known public-side lead, said the spokesperson. Mostly, those are service connections from water mains to a properties boundaries, they said.

“Uisce Éireann has replaced over 61,000 lead connections to the end of 2023,” said the spokesperson.

In its annual report for 2023, the Environmental Protection Agency said that there needed to be more leadership at a national level to drive efforts to reduce people’s exposure to lead in drinking water.

Progress by Irish Water is too slow, they said. “At this rate, Uisce Éireann is highly unlikely to meet its commitment to remove all public-side lead pipework by 2026.”

Not enough is being done at the moment to remove lead from the environment, said Auerbach at the 8 July gathering.

There are still lead pipes in the system which are harmful, he says. “Especially for children.”

Lead pipes were used because they are corrosive resistant, he said. It stopped the pipes rusting and falling apart, he says. “But there is a cost to that.”

Lead can leach from these pipes and lead exposure can damage brain development and the nervous system.

Academic performance and behavioural regulation are influenced by the development of our prefrontal cortex, and the problem is that lead impacts that development, he says.

Kids exposed to lead at a young age can do worse in school and have problems concentrating, he says. “Not saying it will happen, but it can happen and will be more likely to happen.”

That’s why it is really important we remove lead from the water, he says. But “lead pipes are still around”.

Some of the residents say they think the council may not want to change the pipes as the complex is long earmarked for regeneration.

What if they need to wait for more than 10 years before being reallocated? “What’s the price of life?” says Mulhall.

Someone in the audience asked if you can filter out lead.

No, says Auerbach. The only way to protect yourself is to get rid of the pipes, he says.

The National Strategy to Reduce Lead in Drinking Water says that the council “should survey their housing stock to determine the extent of any lead pipework or plumbing”.

“Tenants water is inspected when requested by tenants. The overall pump system in the complex is check 3 times a year on a cyclical basis,” said a council spokesperson on 15 July.

The council spokesperson didn’t directly respond to a query about any plans to replace the pipes in Dolphin House.

“As part of the design for the regeneration the existing network will be inspected and upgraded as necessary. All of the internal pipework will be changed as part of the regeneration,” they said.

The Dolphin House complex was earmarked for regeneration in 2005 via a public-private partnership – but all that evaporated with the crash.

In 2013, a regeneration programme got the green light. But only the first phase has been done so far.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.