What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Plans to reopen Richmond Barracks in late spring seem to be on track, and many in the neighbourhood hope the new attraction will bring much-needed footfall to the area.

On 2 May 1916, the first court martial of the Easter Rising was issued at Richmond Barracks. A century later, this is the date chosen to reopen the long buildings in Inchicore.

Plans seem to be on track, and many in the local neighbourhood hope that once the barracks are open again, they will draw new life into the area.

Richmond Barracks started out as a British Army barracks, which stretched the length and breadth of what is now the residential estate of Thornton Heights. More than 3,000 rebels were held here in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising.

Men and women were sorted in two large courtyards. From the balcony of the soldiers’ red-brick gymnasium, which is currently being restored, the leaders were picked out from the crowd and received court-martials.

“It’s amazing to think that all of the leaders were there,” says Éadaoin Ní Chléirigh, chair of Advisory Group on the Restoration of Richmond Barracks. “Even the ones that didn’t go on to be executed, like Collins, de Valera, Markievicz.”

Other well-known figures held were Arthur Griffith, William T. Cosgrave, Eoin O’Neill, Noel Lemass and Sean T. O’Kelly, she says. Six of the seven signatories to the Proclamation were found guilty here and led to Kilmainham Gaol to be executed. (James Connolly, who was badly injured, was kept elsewhere.)

Once works are finished and it opens as a visitor centre, people will be able to look down from the balcony, from where the leaders were picked out, and experience the story through witness statements, photographs, and videos.

“Richmond Barracks is the missing piece of the jigsaw and will complete the story of the 1916 Rising,” said Lord Mayor Críona Ní Dhálaigh. “We will now see people walking the same roads from Richmond Barracks to Kilmainham Courthouse and Gaol to learn about our history.”

Richmond Barracks was built back in 1810 by the British government to counter the threat of an invasion by Napoleon. In the 1860s, three more buildings were constructed for the soldiers: a gymnasium and two recreation rooms. These are the three buildings still in existence today.

In 1922, the Free State Army took them over and renamed the site Keogh Barracks. Then in 1924, Dublin Corporation converted the barracks into social housing known as Keogh Square, which became notorious for terrible conditions. This was demolished in 1969 to make way for a newer housing scheme, St Michael’s Estate.

These three buildings survived, because they became a Christian Brothers school. Today, one is a HSE primary-care health centre and the other two are being refurbished for this visitor centre.

The centre will tell the stories of those on two sides of conflict – the Irish who fought in the British Army, particularly during World War I, and the Irish who fought against the British Army during the Rising. It will also hold the history of the working-class families who lived there until recently.

Richmond Barracks is trying to tell those forgotten chapters of our history, says Ní Chléirigh.

“We’re looking at the 200 years of the barracks and the people who lived and worked, as well as died, for Ireland. The whole lot,” she says. “It isn’t up to us to say what bits should be told and not told. We just tell it all.”

The restoration isn’t just about revolutionary history, says Mary McAuliffe co-author of Richmond Barracks 1916: “We Were There”, which tells the story of the 77 women held there after the Rising. “It’s about nineteenth and twentieth century social, political and military history.”

She believes it’s important that the centre will capture some of these lost stories, and that this is what people are really interested in.

And as for the British Army? People are really interested in the British Army, it turns out.

“There’s huge Irish interest in it,” Ní Chléirigh says. People may be quieter about this window of history, but more Irish people were actually in the British Army than part of the 1916 Rising.

The group who put together the proposal for restoring Richmond Barracks were from all different backgrounds, Ní Chléirigh says. Some were involved with the British Army, while others were involved in Sinn Féin.

Across from the barracks, the Goldenbridge Cemetery will also reopen as part of the 1916 project. A new path will lead tours to a new entrance in the high stone walls of Dublin’s first Catholic cemetery.

“It’s the first time there’s ever been a tour there, and it’s absolutely fascinating,” says Ní Chléirigh.

Dating back to when there were restrictions on performing Catholic ceremonies in public, political leader Daniel O’Connell bought it in 1828 so that Catholics could have funerals at their gravesides.

This garden cemetery spreads across two acres. Large grey stone slabs and crosses are scattered on the grass. The graves were once found using a grid system, referencing numbers on one wall and letters on the other.

An impressive mortuary chapel, which resembles a Roman temple, stands in the centre of the yard.

Richmond Barracks closed the cemetery in the 1870s because there was an outbreak of cholera. And of course they thought the Catholics in the graveyard were to blame, chuckles Ní Chléirigh.

William T. Cosgrave, who succeeded Michael Collins as chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State, is buried there. And so are two people who died during the 1916 Rising: Cosgrave’s step-brother, Frank Burke, and eight-year-old Eugene Lynch, who were both shot by soldiers.

Ní Chléirigh is confident that the restoration, which will cost nearly €3.5 million when all’s said and done, will be finished on time. It’s the quickest restoration in the history of the state, she jokes.

There will likely be some private tours and school tours in May to give guides practice before the doors are thrown open to the public in June, she says.

“Those buildings would have gone if it weren’t for local people campaigning to keep them,” says Ní Chléirigh, who was part of the campaign herself.

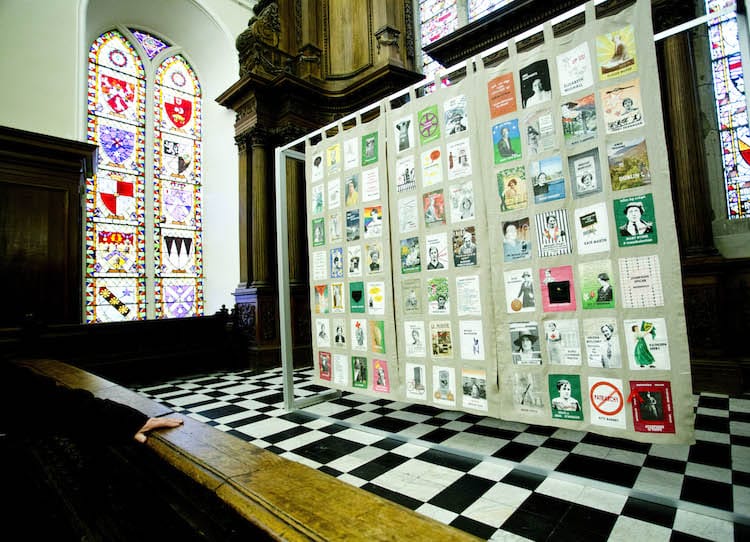

There’s been lots of involvement from groups in this part of the city. For a recent commemoration for women of 1916, some Inchicore women put on some street theatre in the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Others gave time to make a quilt to commemorate each of the 77 women who were imprisoned in Richmond Barracks.

Already, the women who made the quilt want to get sewing and sell stuff over there, says Ní Chléirigh.

The local school facing the barracks has already gotten involved too. Students from Our Lady of Lourdes National School laid a wreath on Lynch’s grave, and yesterday were presented with a tricolour in the barracks as part of the Defence Forces’ Flags for Schools Initiative.

It’s hoped that the new development will bring benefits to the community as a whole. One group that stands to gain are those using the community nursing facility behind the barracks.

They will soon be looking out onto an elaborate garden. “They’ve been so highly entertained by all the building works,” says Ní Chléirigh.

There aren’t many parks nearby and the garden will be open to the public, so Ní Chléirigh hopes it will become a place for reflection. There will be pear trees blooming with white flowers in May each year to mark the anniversary of the leaders’ courts martial. At the back of the barracks, a coffee shop will open too.

“Our hope is that it will become a bit of an energy in the area,” she says. The centre might lead to jobs for the area and promote Inchicore as an attractive place to visit. “It will bring footfall to the shops, it will bring interest to the area,” she adds.

Local Dublin city councillor Daithí DeRóiste, of Fianna Fáil, says the redevelopment is a huge breakthrough for the neighbourhood.

“Inchicore village is a place of huge deprivation, it’s really struggling in terms of footfall, and if we can bring people past Kilmainham Gaol and into the village and then around to Richmond Barracks, well, then they’re going to be spending in the locality,” he says.

He hopes that investment will continue after the centenary year is done, and that tourist trails that bring visitors outside of the city centre will continue to develop.

Already, the area has been given more street-cleaning resources. Councillors and council officials agreed at a meeting in January that dumping and graffiti will have to be dealt with since more tourists are expected in the area.

“Hopefully thousands upon thousands of tourists will be in the vicinity, and it’s really important that what they see is a clean city,” said Ní Dhálaigh.

McAuliffe, the author, said the area needs a boost, and hopes Richmond Barracks will provide it: “It’s giving back to the working-class area, which it’s been a part of for so many years.”

CORRECTION: This article was corrected on 21 March at 9.21 am. An earlier version said that all seven of the signatories of the proclamation were held in Richmond Barracks. In fact, James Connolly was held elsewhere.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.