What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

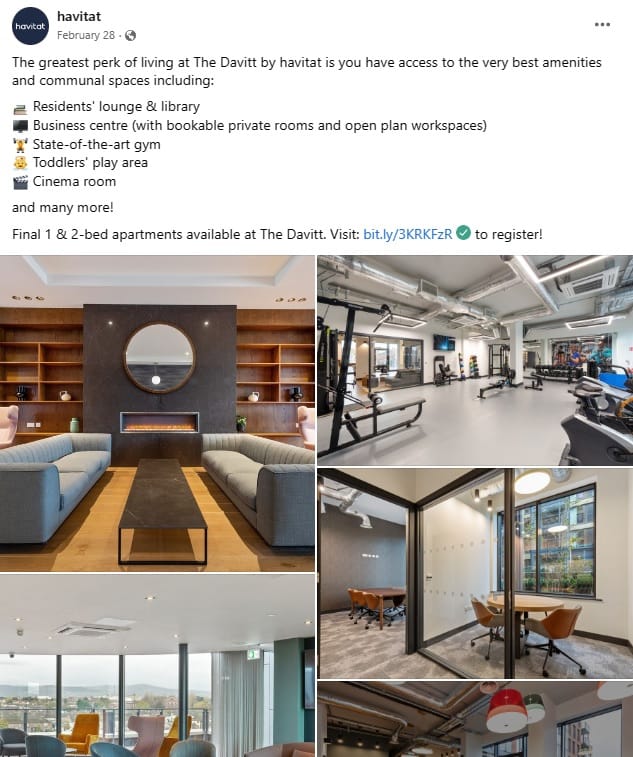

There are wider questions, too, about who has access to the many communal amenities at The Davitt, at what price – and how that fits with planning rules.

Ciaran McCabe flashed the app on his phone in front of a censor by the gate to Block D of The Davitt housing complex in Drimnagh.

Through it is the way to a children’s playground. McCabe has a four-year-old son, full of energy. It’s Thursday 1 June and a sunny afternoon, and his son wants to play.

McCabe pulls and pushes at the door. It stays shut.

The evening before, another tenant, also a father, had demonstrated similar. He too, couldn’t open the gate that leads through to a playground.

In fact, all the neighbours in his block – which is where the social-housing tenants live in the mostly private-rental complex – have the same problem, says McCabe. Even though there are plenty of toddlers living there, some with special needs.

It’s difficult for parents to explain why they can’t use the playground, he says. Especially since the adults don’t understand it either.

A spokesperson for Tuath Housing, which manages the social housing at The Davitt which is leased from the owner, said tenants do have access to a children’s playground and have many methods of access, including a fob and a passcode, and the mobile app.

And all residents, social or otherwise, “have an opportunity to avail of other additional amenities, such as a gym and communal workspace area, by paying a fixed monthly fee”, they said.

But social housing tenants say it just isn’t true that they have access to the playground behind the Block D gate. They’re locked out, they say, from that and from all of the community and recreational amenities.

A spokesperson for Avestus Capital Partners, an advisor to the property owner, said they had been unaware that the Dublin City Council tenants had been restricted from accessing the playground area and have liaised with Tuath to ensure access is granted to those residents.

McCabe says he is just going to pay extra for access to the amenities, which include an indoor kids play area, on top of his rent. “So my son isn’t just locked away in this one block.” (He tried before, he said, but hadn’t heard back.)

But it’s still different from the private-rental tenants he has talked to, he says, who told him they don’t have to ask when they move in if they can have access and don’t have to pay extra on top of the advertised rent.

Planning documents, on the basis of which the complex was granted permission, note the extensive amenities and play areas for all residents, with no mention of some being shut out or of extra charges.

The complex was built to what are known as build-to-rent standards, under which developers were allowed to trade off less private space and storage in individual apartments, in exchange for more communal amenities.

Planning guidelines for these kinds of rental complexes stressed the importance of shared amenities in helping those living there get to know their neighbours, and feeling that they belong.

Dublin City Council didn’t respond to queries as to how this had come about, and whether a lack of access to amenities for social tenants is a breach of planning.

“Before I signed the contract I was told we had access to it,” says McCabe. Nobody suggested they wouldn’t be able to use the full range of amenities advertised online, he says, which he had read about.

He chose to live here because council staff said that there would be a community vibe, with shared amenities and regular social events, says McCabe, who works as an actor.

“It was for the social aspect, the whole community feel,” he says. “It’s quite the opposite of that.”

The segregation has made him feel upset and angry, says McCabe. He struggles to put the exact feeling into words. “It’s not fair at all,” he says.

“You feel like it’s us and them,” says McCabe. “It should be all just us.”

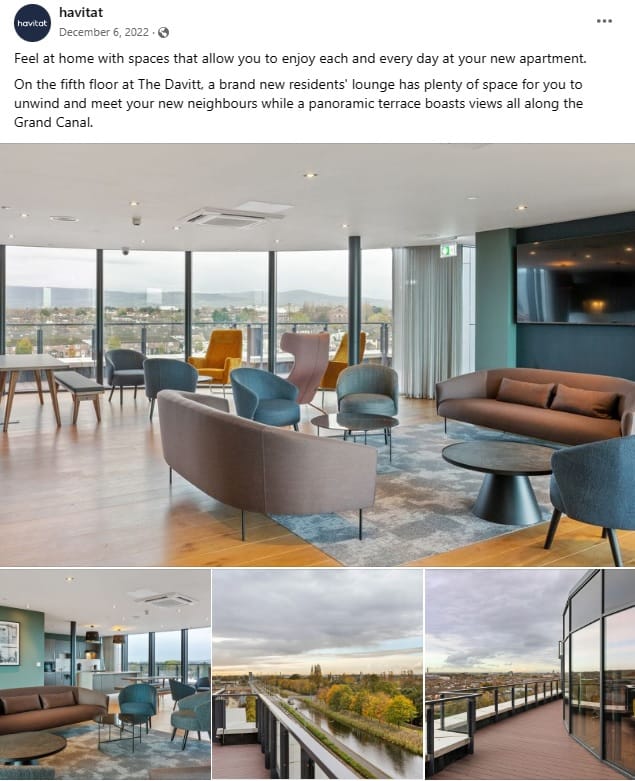

There are 265 homes across four blocks in The Davitt complex which sits alongside the Goldenbridge Luas stop, overlooking the Grand Canal.

Of those, 26 are leased to Dublin City Council for social housing, say council reports, as part of the arrangement known as Part V, whereby developers of big schemes have to sell or lease a percentage of the homes to use for those most in need of housing. One of the drivers of Part V is to counter social segregation.

The social homes at The Davitt, all clustered together in one block, are managed by the housing charity Tuath Housing.

The developer’s original planning application for The Davitt, which was approved in April 2019, noted, among other amenities, two large private courtyards with children’s play areas “for the benefit of all residents” of the four blocks.

It also says how the plan was for communal facilities and amenities in one of the blocks “for all residents”, listing a reception, media centre, gym, games room, and shared party room, among other facilities.

When permission was granted, one condition was that the developer had to send in a detailed built-to-rent management plan, laying out how it would manage the complex.

It did that. The document doesn’t mention anywhere that some of the amenities or communal facilities would not be accessible to all of those living there.

The built-to-rent guidelines in place at the time, which were drawn up by the Department of Housing, stressed how “dedicated amenities and facilities specifically for residents is usually a characteristic element” of these developments.

Indeed, they contribute to community, said the guidelines, and “to the creation of a shared environment where individual renters become more integrated and develop a sense of belonging with their neighbours in the scheme”.

Also, because of the extra community facilities and amenities, developers could trim down the amount of storage and of private and communal amenity space per apartment, the guidelines said. As long as residents had an “enhanced overall standard of amenity”, they said.

Avestus Capital Partners announced in December 2019 a forward-purchase agreement to acquire The Davitt, and announced in September 2022 that it had completed the acquisition.

Herbert Park ICAV (Irish collective asset-management vehicle) was registered that same month with the Property Registration Authority as The Davitt’s owner. It’s unclear who Herbert Park ICAV’s shareholders are.

A spokesperson for Avestus Capital Partners says it is an advisor to the owner. Avestus Capital Partners’ website lists The Davitt among its “assets currently under management”.

McCabe’s apartment has laminate floors, a white kitchen with an island and a large balcony. “The apartments themselves are great,” says McCabe. “They’re lovely.”

However, the segregation, and being locked out of amenities, has left him with such a bad feeling that he now regrets accepting this home, he says.

His family were among the first tenants to move into the complex last October, says McCabe. At first, his fob let him buzz through all the gates and doors in the complex.

But after a few weeks and the launch of a new app, one day in November 2022, he found that he couldn’t let his son into the playground, he says. “He was a bit upset, he was confused.”

Naturally, his son still wants to go and play in there, McCabe says, and still asks to go in.

McCabe pulls out his phone. Tenants have an app and a fob, he says. The app has a section for “amenities”. “No Amenities Yet”, it reads.

Another screen shows that McCabe has access to three doors: the main gate, the gate to his own block C, and the door of block C, he says.

When he discovered he couldn’t get through the doors and gates to the communal facilities he was shocked, he says.

Many of the social tenants have young children, he says. All the kids need somewhere to play.

One of his neighbours has a daughter with special needs and he also really needs a car-parking space. “That should be a top priority,” says McCabe.

A spokesperson for Tuath Housing said it has a thorough interview and pre-tenancy process that clearly outlines the details of a resident’s tenancy agreement.

“As well as outlining the full range of services provided to ensure the experience in their home is a safe, secure and sustainable one,” they said.

But McCabe says he was given a drastically different account before he rented of what would be available to his family.

Council staff had told him how great the complex would be because of all the community facilities and social events, he says.

He was warned, when signing the tenancy agreement that he wouldn’t have a parking space, he says. But they followed that up by telling him not to worry about amenities, he says.

That surprised him, McCabe says. “I remember specifically saying back to them, what do you mean not to worry? You told us we have access to this.”

When he discovered that he couldn’t get into the playground, at first he thought it was a temporary issue and he called Dublin City Council, he says.

They told him to phone Tuath, which told him to ring the council, he says. “They just kept sending me back and forth.”

Eventually, someone told him to talk to the property managers for the complex, he says, and the property managers said he could pay extra to use the communal facilities.

McCabe says he has agreed to pay €81.50 a month so that his family can use the facilities.

Neither Dublin City Council nor Tuath Housing has explained any of this, he says. “They never even gave me a reason why we need to pay the extra money, they never even talked to us about it.”

Staff from Tuath Housing said the social tenants should have access to the outdoor playground, he says, but they didn’t ensure they got it or explain what was going on with the other amenities. “They still haven’t given me a straight answer at all.”

Says McCabe: “They should have been a lot more transparent about this whole situation. They constantly keep not answering questions, which is just building up the tension.”

Dublin City Council reports give different figures for the number of social homes leased last year as part of bigger developments, through Part V agreements with private developers.

A January 2023 report says 111 homes, while a February report says 128 homes. Not all of them are necessarily in build-to-rent schemes.

Dublin City Council didn’t respond to queries about whether it has agreed to arrangements that shut out tenants from amenities when negotiating the leases for social homes that are in build-to-rent complexes.

UPDATE: At 13.07 on 7 June 2023 this article was updated to include comments from a spokeperson for Avestus Capital Partners.

CORRECTION: At 15.02 on 7 June 2023 this article was corrected to reflect that Avestus Capital Partners is not the owner of The Davitt, and Herbert Park ICAV is.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.