What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Jeffrey Roe is running a workshop at the TOG Hackerspace next month for those interested in making their own sensors, to track air pollution in their neighbourhoods.

In the common room of the TOG Hackerspace in Blackpitts, Jeffrey Roe opens an app on his phone.

A line on a graph on the screen creeps up and down a little, but is more or less even – before rising up into a sharp peak. It shows readings from the air-pollution sensor, across the city, outside his home in Crumlin.

There was a spike at 4.30pm, earlier that day. “Why were people busy then?” he says, with a chuckle.

Another graph, for a few months ago, the night of Halloween, shows a thin line rising sharply from the early evening, as bonfires light up. “You can see, when it starts to get dark, the level of pollution just skyrockets,” he said.

Roe can track in real-time how noxious the air in his neighbourhood is, thanks to a U-shaped home-made sensor stuck to the outside wall of his pebbledash home.

It’s one of 16, he estimates, that he has so far made with other Dubliners as part of a wider citizens’ science project tracking air pollution on a local level – and with the open-source data feeding into a global network.

Roe says he hopes people start to link pollution sources around them to the spikes they see through monitors.

“Hopefully, they associate these and make it data-driven. So they understand that these things have a real impact on their lives,” he says.

He’s running a workshop next month for those interested in making their own air-pollution sensor. Interested groups can contact him directly, too, he says.

Roe made his first air-pollution sensor last year, he says. It all started when Melissa O’Callaghan contacted him.

O’Callaghan had read online about Ella Kissi-Debrah, a nine-year old girl in London who died in 2013, after an asthma attack. Her parents are pushing for the cause of death to be marked as pollution.

O’Callaghan has a daughter with asthma. She found it deeply upsetting, she said, recently. “It really struck home with me.”

She started to look into air-pollution rates here in Dublin and was shocked, she says. “I’ve probably been ranting on about this, the past year.”

That was one trigger. Another was learning at a conference that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had a monitor in St Anne’s Park – between Raheny and Clontarf, the part of the city where she lives.

But then, that it had been turned off so there weren’t any readings, she says. “I was like: what?”

According to an EPA spokesperson, Dublin City Council monitored air quality at St Anne’s Park up to 31 December 2015, when the station was closed due to “health and safety issues”.

The EPA and the council then put in a new monitoring station, which began to put out data on 5 September 2018, they said.

In her online research, O’Callaghan learnt about the build-your-own air-pollution sensors and got all the parts on eBay, she says. “Then, I kind of needed help.”

So, she found Roe.

At the TOG Hackerspace in Blackpitts, a comfy kitted-out warehouse, people can pay between €20 and €45 a month to come and tinker and build and craft.

“People follow their hobbies, follow their passions,” says Roe, on a recent Thursday evening, as he gave a quick tour of the rooms stuffed with tools, equipment, and parts.

There’s welding, drill presses, lathes, CNC machines. Sewing machines, knitting machines, oscilloscopes and semiconductors.

In one room, a 3D printer whirrs as it reshapes a spool of neon-orange plastic. “It’s a cable holder,” says Roe, leaning over for a closer look. “It’s got an hour left to print or so.”

In another room, there are empty bottles and plastic vats for brewing. “I’m not sure much about the brewing process. But you walk by and stuff is bubbling,” says Roe.

There are a couple of old motorbikes, and the frame of a bed with a pulley, and the skeleton of a small handmade boat, made with golden wood.

“We have this ebb and flow where the space gets full of stuff and we do a clean-out and it slowly accumulates more stuff,” says Roe.

One guy is making a bar-tending robot. “He wants a robot to make G&Ts for our birthday,” he says. The group is on the cusp of their 11th year.

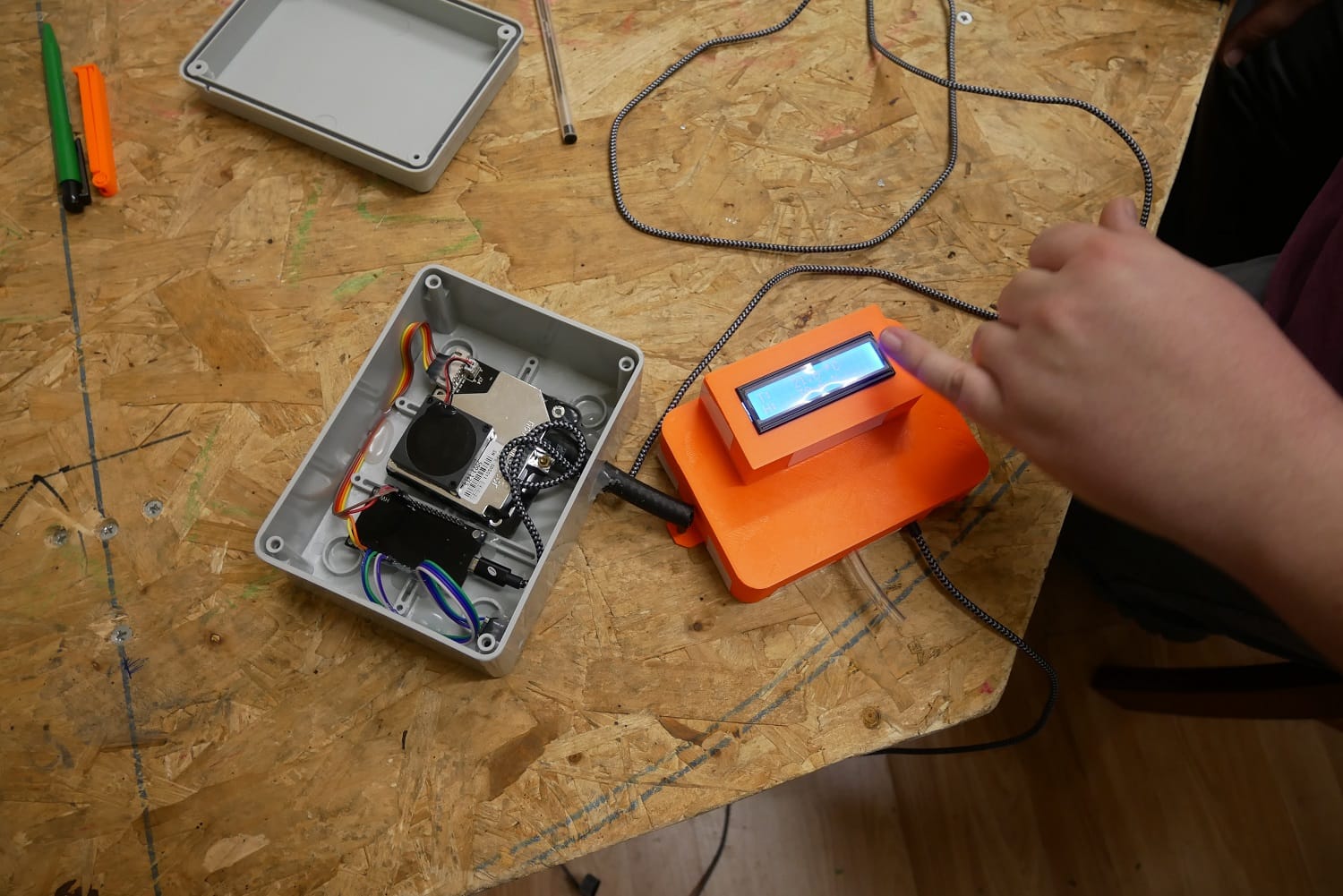

Among the gadgets that Roe has built here are air-pollution sensors.

The bones of the project came from Luftdaten, a German group which has led a global movement, guiding people on how to build their own sensors and measure air-pollution levels outside their homes.

They publish a shopping list and construction manual online.

There are now thousands of citizen-made sensors spread about the world, with pockets where groups have come together, says Roe.

There’s a growing interest in Dublin. “There’s been about 16 built, but they haven’t all gone live yet,” says Roe.

Assembling the sensors is pretty simple – there’s no soldering, for example. That’s down to the underlying philosophy, says Roe. “To not get too bogged down in the tech side of it.”

The programming is easy to set up too, he says. “They’re demystified all the tech behind it. They’re really trying to make it citizen-led and not tech-led project.”

The parts are consumer-grade rather than industrial. To keep costs down, he says. What works elsewhere, doesn’t necessarily work here for that.

Luftdaten suggests a particular kind of U-shape pipe as the casing. But while it costs roughly €5 in Germany, it’s a steep €35 here. “That added a lot to the price of the kit,” he says.

The idea is to buy consumer-grade hardware to keep the cost at around €30. “Not have the thousands-of-euro, kind of, professionally calibrated sensor,” he says.

When, a few weeks after he and O’Callaghan made their first sensors, he led a workshop with Green Party Councillor Sophie Nicoullaud for her and her colleagues, they opted to use an electrical box, instead.

“This is something you can get from your local electrical wholesaler,” he said. “And people are much more happy to have something like this stuck to the outside of their house.”

Because the project is all open source, people have remixed it to suit them, he says. He’s trying to make a battery-powered version for those unable to link to a power source.

There’s a smokey metal smell in one of the TOG workshops. High up on the wall is one of the air sensors.

This one has a screen, so people can see the readings in real time, rather than having to log onto the internet.

“It’s mainly for tall people, unfortunately,” he says, peering up at it. “It’s more a visual or mental aid to remind people to put on their mask.”

He’s planning to make three or four of them, says Roe, later. “Then, to loan them out to events and stuff. So if people are using, particularly outdoor events if they’re using diesel generators and that sort of stuff.”

Roe points to the sensor within the open electrical box on the table in the common room. “Every three minutes it sucks a sample of air up into the sensor,” he says.

It then detects how many of a particular size of particle, PM2.5, are in the sample. Those ones are particularly harmful. (The PM10 value is estimated.)

“What we typically know is that fossil fuels, when they’re burnt, they release a lot of that particular size of particle,” he says. “We use that to indicate the pollution level.”

It has a micro-controller that connects to Wifi and feeds it back to the Luftdaten website, where anybody can look.

It’s open-source data and has a map. “They do some filtering on the raw data to even it out,” he says.

Since his earliest workshops, Roe has done bits and pieces with people as they’ve come to the space and a workshop for 20 people in Leipzig at Christmas. “The demand has been slowly building up now,” he says.

If people want to get involved and make them, “They can come to our workshop coming up,” he said. That’s on 29 February – during Engineers’ Week.

“If larger groups get together, they can contact us through info@tog.ie, and we can arrange another workshop or whatever,” he said.

Sign up here to get our free email newsletter each Wednesday, with headlines from the week’s online edition, updates from inside the newsroom, and more. It’s a little reminder when we have a new edition out, and a way for you to stay in touch with what we’re doing without having to check social media.