Councils are unlawfully refusing people access to homeless accommodation, say lawyers

“You shouldn’t need a solicitor to access homeless services,” says Adam Boyle, of the Mercy Law Resource Centre.

The group show Weaving Threads of Heritage opens 12 April at Ardgillan Castle.

Petra Skyvova slipped on a pair of white gloves and opened a grey vintage suitcase.

Inside the case, on the checked lining, someone had written the name of the town’s old hosiery manufacturer, Joseph Smyth and Co.

Around her in a quiet section of Balbriggan Library, students studied and people browsed bookshelves.

Skyvova delicately emptied out the case’s contents: a plethora of products made in the factory.

There was a pair of brown silk stockings with a black and gold badge reading “Balbriggan Fingalette”.

There was an orange cotton top with a striped black collar, and a pair of pantyhose from the 1960s, folded into packaging that featured photographs of women sitting, one inside a seashell, another by a sofa stroking a basset hound.

Next, she produced three leather-bound catalogues with rectangular samples of black cotton, into which someone had stitched elaborate patterns, abstract and floral.

They are all fine Balbriggan cotton, she said. “The embroidery is pure silk, and I think done by hand.”

These catalogues were hard to date, she said. “I think they are from the 1890s, 1900s.”

She leafed through one of the books, and folded another out, like an accordion, until the entire desk was covered by these vintage samples.

This collection of products manufactured by the factory are in her custody as she puts together an arts exhibition, Weaving the Threads of Heritage.

Due to show in Ardgillan Castle between 12 April and 11 May, the exhibition brings together eight local artists, who will interpret these items to create works that reflect on Balbriggan’s heritage, she says. “Because these stockings and its textile production used to be very well known.”

Balbriggan, to locals, is a place name.

But around the world, in the 19th and 20th centuries, a “balbriggan” meant a finely knitted cotton fabric, Skyvova says. “Look it up in the English language dictionary in lowercase. It’s a noun, which is remarkable.”

Inside the suitcase, Skyvova kept a booklet, printed in the 1940s.

It featured photographs of the factory workers going about their duties in the old factory on Railway Street, and included some text, including an introduction written by the author Brinsley McNamara.

“Everyone has wanted, but not everyone has been able to get, what only Balbriggan could supply. Yet everyone has come to know the difference sooner or later,” he wrote. “That is why there can be only one place of the name. And that name has come to mean only one thing, the perfection of a craft.”

Like how sparkling wine can only be referred to as champagne if it is produced in the Champagne region, a pair of balbriggans could only come from this place, Skyvova says as she holds a pair of stockings in her gloved hands.

“The weavers here were so skilled, and the cotton they produced here was so fine and luxurious that it was recognisably unique,” she says.

Skyvova took a photograph out of a folder.

It showed a black and white picture of a stern Rasputin-looking man named Thomas Mangan. He wore a top hat, and his eyes were wide enough to distract from his long, thick beard.

“This gentleman was a third generation weaver,” she says. “He was extremely well-known and skilled.”

Mangan was personally recognised by Queen Victoria I for his work, she says. “In 1888, they sent him a picture, signed by Victoria here in the courthouse.”

The whereabouts of the picture of the queen are currently unknown, she says, but she produces a photo of the photo. “This is an analogue photograph of the actual image in the frame.”

The adoration for the fabric travelled all over the world, she said, with its name remaining in the popular lexicon until about the 1970s. “People would have, especially in America, used that word.”

There is an anecdote from the 1930s. Four American women were riding the train from Dublin to Belfast, local historian David Sorensen says. “It happened to stop in Balbriggan, and one of the ladies was very excited, because she saw the name Balbriggan. It was like seeing a town called Weetabix.”

One urban myth that Sorensen has been investigating for years is an alleged deleted line of dialogue from the 1950 John Ford-directed western Rio Grande.

John Wayne’s character, Lieutenant Colonel Kirby York is believed to have insisted that he couldn’t go without his balbriggans, he says. “I’ve got people to look through all the scripts. But I’ve never been able to track it down.”

The layout of Railway Street today has been built around the old Smyth and Co. factory.

Its buildings are situated on both sides of the street that leads out of the train station, with the facades still decorated to preserve its legacy.

The old signs are still mounted to the walls out on the street, announcing that it was established in 1780, and earned medals at exhibitions the world over: London in 1862, Vienna in 1873, Philadelphia in 1876 and Paris in 1878.

Mounted to the walls along the street in more recent years are large, blown-up black and white photographs of the factory in its heyday, showing workers in long white coats on the production line, weaving and standing outside the building.

That heritage trail is the work of Petra Skyvova, she says.

The factory ceased production in 1980, says Sorensen, the local historian. “It went into liquidation and the machinery was all sold.”

In the mid-1990s, one of the factory’s buildings was repurposed as a series of artist’s studios, known as Sunlight Studios.

Murielle Celis, a Belgium-born artist, and one of the contributors to Skyvova’s show, lived and worked out of the studios, Celis says, around the corner from the library in The Window print studios on Dublin Street. “I came to Balbriggan because of the studios.”

When Skyvova came in to visit Celis in The Window, the artist was setting out a few of the works she was developing for the group show.

Celis had taken as her subject matter different details from the items in Skyvova’s suitcase collection, etching into the surfaces of square blocks of wood larger versions of the leafy silk embroidery patterns, old logos and styles of lettering used by the company, and a handwritten index contained in one of the old catalogues.

She used a laser engraver, she says. “I’m filling up the grooves with a powder coat paint.”

The paint gives each of their surfaces a cloudy patina, to convey the feeling that these works have been weathered by decades and centuries. Celis had also created layers of lettering, with some fonts appearing only faintly underneath others.

She wanted to pay homage to how much thought the company gave to its lettertypes, she says. “Some of these letter types were imprinted with gold into some material and textiles.”

Liz Comerford wandered through The Window studio on Saturday, just after lunchtime, searching for the various one-of-a-kind art books that she had created.

Comerford too had worked as an artist in the old factory, she says. “I knew it was a factory, but didn’t pay much attention to its history.”

A self-taught printmaker, who learned much of the craft from watching YouTube tutorials, she was in the early stages of a project to hand-make 100 different books, Sykvova said. “These are books like a dragon-scale book and pop-up books.”

The dragon-scale book was one Comerford was concocting for the exhibition. It was in the shape of an elongated female leg, modelled on the wooden planks cut to fit a stocking for display.

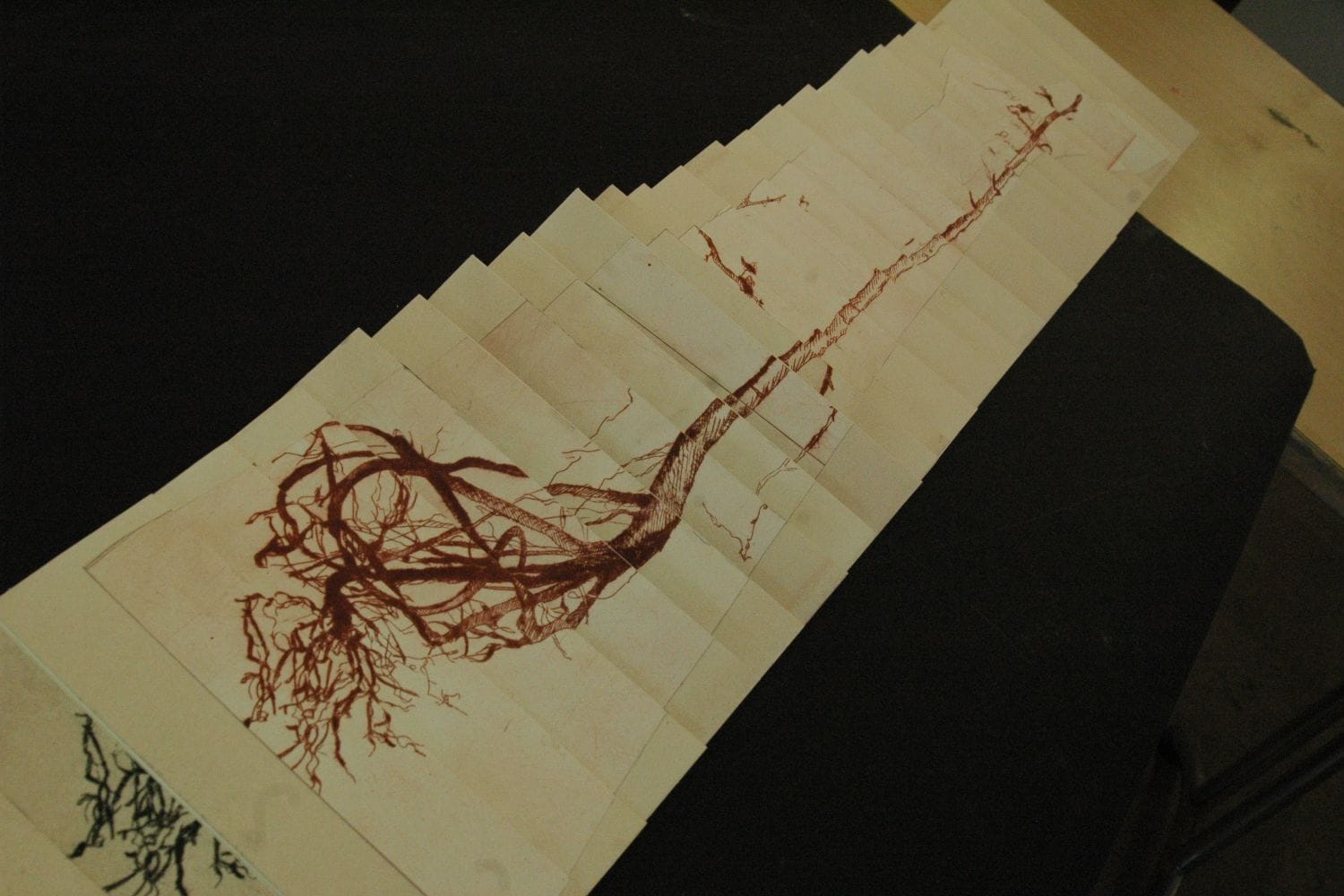

Laid out on a desk in the studio was this book, with each of its pages designed to fold out to resemble scales, and as the scales moved about, it revealed a different image.

She opens it out one way. It shows a black, white and brown collage, comprised of nature and bird-like abstract illustrations, with found objects like a small elastic fastener for an undergarment fixed onto coarse pieces of hand-made paper.

She folds it out another way, and the pages turn into a red, finely illustrated branch of a hawthorn tree. “It is very reminiscent of the veins that go through your leg,” she says. “And the leg is the thing that attracted me to this.

“I thought it would be the embroidered patterns. Because I love patterns,” she says. “Some of my books are nothing but patterns.”

The exhibition, Weaving the Threads of Heritage, is a celebration of history, but also how this heritage continues to influence the town, Skyvova says.

While she and seven other artists will have pieces on display, she also wants to display some of the actual items from the factory, putting works of art and craft side by side, she says. “I want artists to be able to use artefacts in a different way, rather than having it sitting in a museum.”

There are so many items that sit in the archives of museums, not on display, fulfilling very little purpose, she says. “So I want to see how it speaks to you today.”