What’s happened with Manna’s plan to expand its drone delivery service across Dublin?

It still only has one base, in Dublin 15, with planning permission – and that’s due to expire this year.

Maria Ginnity’s show, In Transit, is set to open at Reds Gallery on Thursday.

Temporarily, Maria Ginnity’s living room had become a gallery devoted to Luas passengers.

She sat the canvases in armchairs, on the dining table, and propped them up against walls and the back of her sofa.

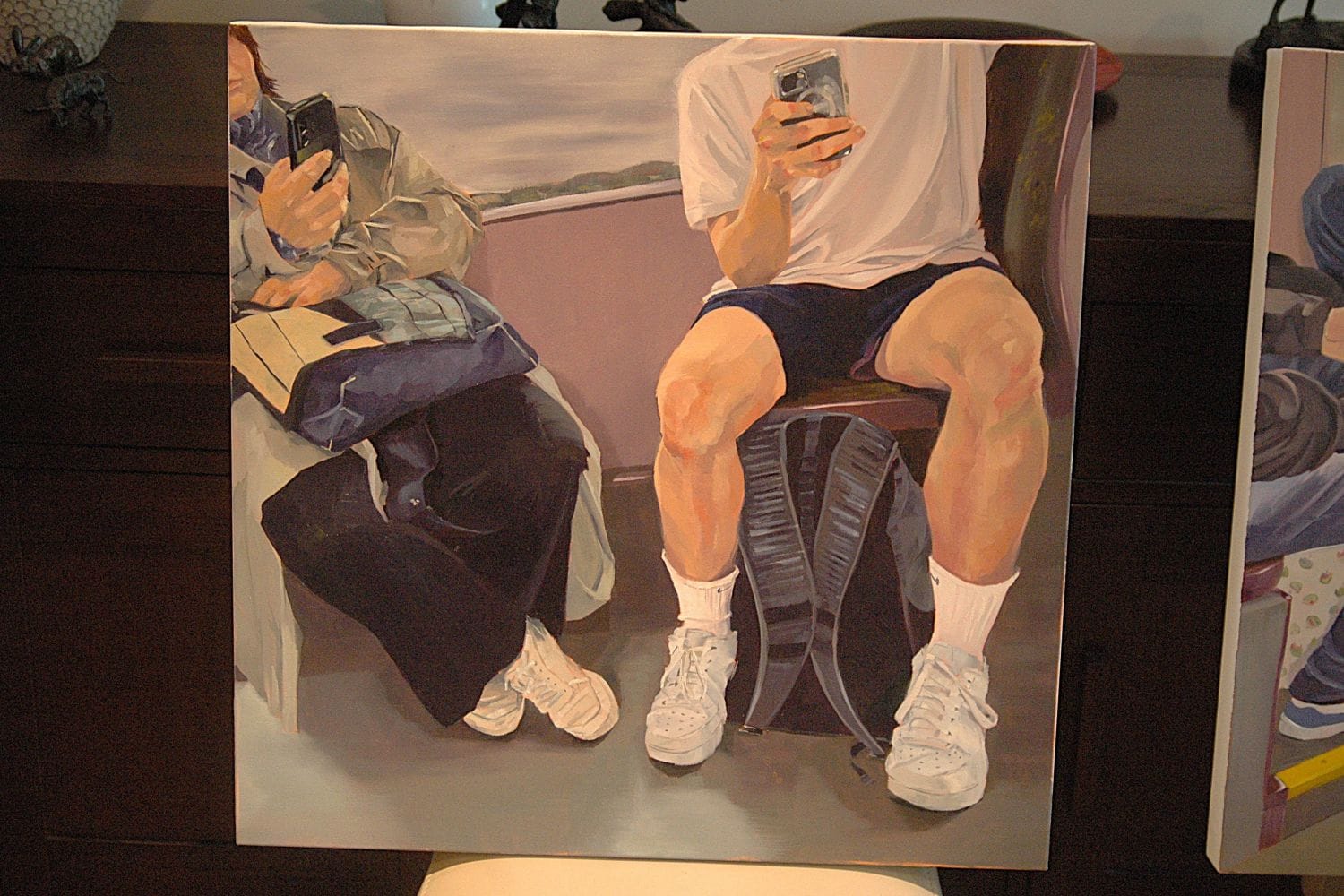

Each of the oil paintings had focused on a character or two, mostly from the shoulders down, as they took a seat on the tram.

Some had angled themselves awkwardly across a seat and a half. Others timidly kept their legs close together, their feet turned inwards.

More than a few scrolled their phones, while one outlier immersed himself in a book, and, Ginnity says, “you don’t see that often now”.

The only subject she chose to paint who wasn’t in a tram carriage was a girl with a backpack, immersed in her phone, while waiting for her Luas to pull up at the Balally stop, a few minutes north of Ginnity’s apartment on the outskirts of Dundrum.

All of the works, which make up Ginnity’s second solo exhibition, In Transit, launching in Reds Gallery on Dawson Street on Thursday, are studies of people seeking privacy while occupying public spaces.

It’s something that has fascinated the artist, be it people in airports or on a tram, she says. “Or even by the swimming pool. We go away to relax, but we’re jammed together like sardines.”

She likes to see how people cope when they are in this intimate proximity with strangers, she says, while pouring water over the coffee grounds in a French press by her kitchen sink.

Everyone has their own way of setting up those guardrails, she says. “People use their phones or they hug their bags. Men spread their legs. Women she-bag, a concept I wasn’t aware of, where they put a bag on the seat beside them.”

“A sense of self-protection comes into it,” she says.

Ginnity was born in Santry. But her family moved around quite a lot during her childhood, she says. “I think I was in 10 different houses by the time I was 10 or 11.”

“I always had this sense of being the new girl, this sense of outsidedness,” she says. “Just a little bit removed from whatever was going on.”

That might permeate into her work a little, she said, musing over the thought while sipping a cup of black coffee on the sofa in her living room.

She first began to pursue art at Dún Laoghaire College of Art and Design, now the Institute of Art, Design and Technology, in the mid-1970s, she says.

But she detoured from it upon graduation, she says. “I suppose it was the practicalities of making a living.”

She had a whole career in both the public and private sectors before finally returning to the arts in 2020, she says. “I left and went back to my love.”

And, it was while she went to study at the Royal Hibernian Academy School that the In Transit project came about just over a year ago, she said.

Propped up against the brown leather sofa in the living room was a painting of a man’s lower half as he spread out across one of the purple seats next to a door in a Luas.

His light brown briefcase was resting on his lap as he read a book, and he stretched his left leg out in front of him while the right was positioned under the folding plastic seat.

That was the scene that started this interest, she says.

It had been particularly bright outside and the way in which the beams of sun flashed as the tram went along its way attracted Ginnity, she says. “You had this beautiful light.”

But what really captivated her was how this unknown man was looking for privacy on public transport, she says. “It was like he was saying ‘I might be on the Luas, on public transport. But I’m almost at home.’ He just created this space for himself.”

Over the course of a year, Ginnity would board the Luas’ Green Line, and with her phone, quietly snapped photos of anonymous passengers, she says. “There’s an awful lot. I’d say I had 700 photos. An awful lot of rubbish in it.”

A lot of the time, it meant occupying a seat and hoping someone interesting-looking would pull up nearby, she says. “It was a little bit luck of the draw, but I began to get a bit more clever about where I wanted to sit myself.”

Most of the subjects occupied seats in the spacious area of the Luas just inside the exit.

Body language and attire intrigued her. Like, for instance, how people sought to distinguish themselves through the shoes they wore, she said while walking through her hallway into her study, where a few smaller works hung on the walls.

She points to one particular piece, wherein the subjects are two pairs of feet.

The first are wearing a pair of heavy black boots, firmly placed on the purple floor speckled with bits of yellow.

The second, meanwhile, of a woman in her mid-50s, she says. “She had on a lovely coat and gold shoes.”

Her feet, however, were pointed inward. “They were very apprehensive feet,” she says, with a smile. “She came across as being very nervous.”

Each person sets their own atmosphere in those carriages, says Brian Fay, an artist and senior lecturer in fine art at TU Dublin.

“Without over-reading into it, these are paintings that couldn’t have been done over Covid, and what you see is people getting used to being together again,” he says.

With that come a lot of complex, awkward and tense interactions, he says. “We’re still working through it.”

Hands are something Ginnity is particularly keen on studying.

As she took a seat once again on her sofa, it was beneath a triptych of paintings depicting hands, and on the coffee table next to her, there was a book simply titled Hands.

“Our life and how we live is evident in our hands,” she says.

Ginnity’s subjects are faceless. It’s an approach she took both to preserve their anonymity and to ensure she wasn’t noticed taking pictures of passengers during the research stage, she says.

And in the absence of faces, a lot of the personality of her characters in In Transit are emanating from how the passengers use their hands.

Even those people who are holding their phones seem to convey their feelings through their hands, she says. “There is a tension or a busyness.”

Public transport, as an environment, varies from city to city, but being in those spaces can be intense, says Silja Laine, a cultural historian and member of the Putspace project, a European research initiative, which analysed public transport as public space.

It is a space in which the diverse make-up of a city is highly visible, she says. “And, if you’re white, middle-class, in a European country, you’re quite invisible and can establish your own space more easily, because people aren’t looking at you too much. Your travel experience is easier.”

“You’re surrounded by strangers, and at the same time, they are very close to you,” Laine says. It’s why people often focus their attention on things like phones or a book, she says.

“Also, in most countries, it’s considered quite impolite to be staring at strangers,” she says. “You have to keep your eyes somewhere, and if you’re in the underground, there’s not much to get out of the window, so reading’s a good thing for that.”

Just one of Ginnity’s subjects is content to wait out the journey without entertainment, spending the time instead staring out the window.

Being on transport can feel like a kind of “dream time”, Laine says. “It’s also a time where you concentrate on entertainment or reading or writing messages to friends or whatever.”

But, she says, it is also a space that invites us to question whether we always need to be busy or productive. “Do we always have to work, or look as if we work all the time? Or are we allowed to be unproductive for a moment?”

So many of the people she observed had an aura of busyness about them, Ginnity says, before looking back to the man happily gazing out at the city. “It was just the most beautiful photograph, because he was so collected, calm, serene.”

“Some people just use the space and the time they have to just be for a little while,” she says.