What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

For her debut solo exhibition, performance artist Venus Patel drew on the experience of being feared and “seen as a monster” because she is different.

Leading up to her debut solo exhibition “Monsters of the Apocalypse”, artist Venus Patel tried street preaching.

She did it a few times. Most recently, on the Saturday of the Easter weekend, she says.

The hot spot for preachers in Dublin is outside the General Post Office, where O’Connell Street meets Henry Street. Patel had become particularly enamoured by one nun who often performed at this corner, she says.

The nun had gained a reputation online for her energetic dancing and arrest last June, says Patel. “Whenever I watched her, there is just so much performativity in her work, and the way she falls on the ground. I felt like that was one of my main influences for this.”

The sermon that Patel, a trans performance artist, read to O’Connell Street was titled “Queer World Manifesto”. “Some people were angry, and told me to shut up,” she says. “Some people actively listened.”

Near her on Easter Saturday, another preacher stood, sharing his own lengthy message, she says. “I feel like our sermons blended in some ways, and it was funny to put myself into that, because these people are generally not people who would accept me.”

Despite their opposing values, Patel says she nonetheless felt a certain affinity with the preacher as they both relayed messages to a crowd, largely indifferent.

“I feel like because there is a conformist mindset here, in public and in general, people will other anyone that looks different,” she says.

The relationship between what is classified as “the norm” and “the other” sits at the heart of Patel’s work.

In “Monsters of the Apocalypse”, she examines this divide by juxtaposing surrealist performance art with everyday Dublin and its public spaces.

Patel’s voice, singing in the solemn style of a Gregorian chant, echoed around the Pallas gallery space last Thursday evening.

In the centre of the room sat an octopus-like sculpture made from a pair of cardboard boxes, with green and blue papier-mâché domes and purple sequined tentacles.

On the walls were framed photographs of Patel in elaborate costumes, wandering about Dublin. In one, she stood on-board a Luas with her head covered by a cardboard eye. In another, she pushed a trolley through a Tesco, with a long strip of brown paper strapped to her back and rolled up like a snail’s shell.

Playing on a loop in the next room was a seven-minute film, which put the photographed scenes in motion.

It featured members of the public observing Patel as she strolled supermarket aisles, writhed on the streets of the Liberties, and spread her wings, made from painted red paper plates, while journeying along the Green Luas line.

The costumed characters are her “monsters”, Patel says – beings that exist within nature but who are set apart from it, treated as abominations. “Sometimes in society, I feel I am seen as a monster, being a transfemme of colour.”

“I’m different, and there is so much fear that comes with that,” she says. “But I wanted to stress that there is so much beauty in monstrosity.”

Just after 6.30pm, Patel entered the Pallas gallery, stepping through a crowd that had congregated around her tentacled cardboard-box monster.

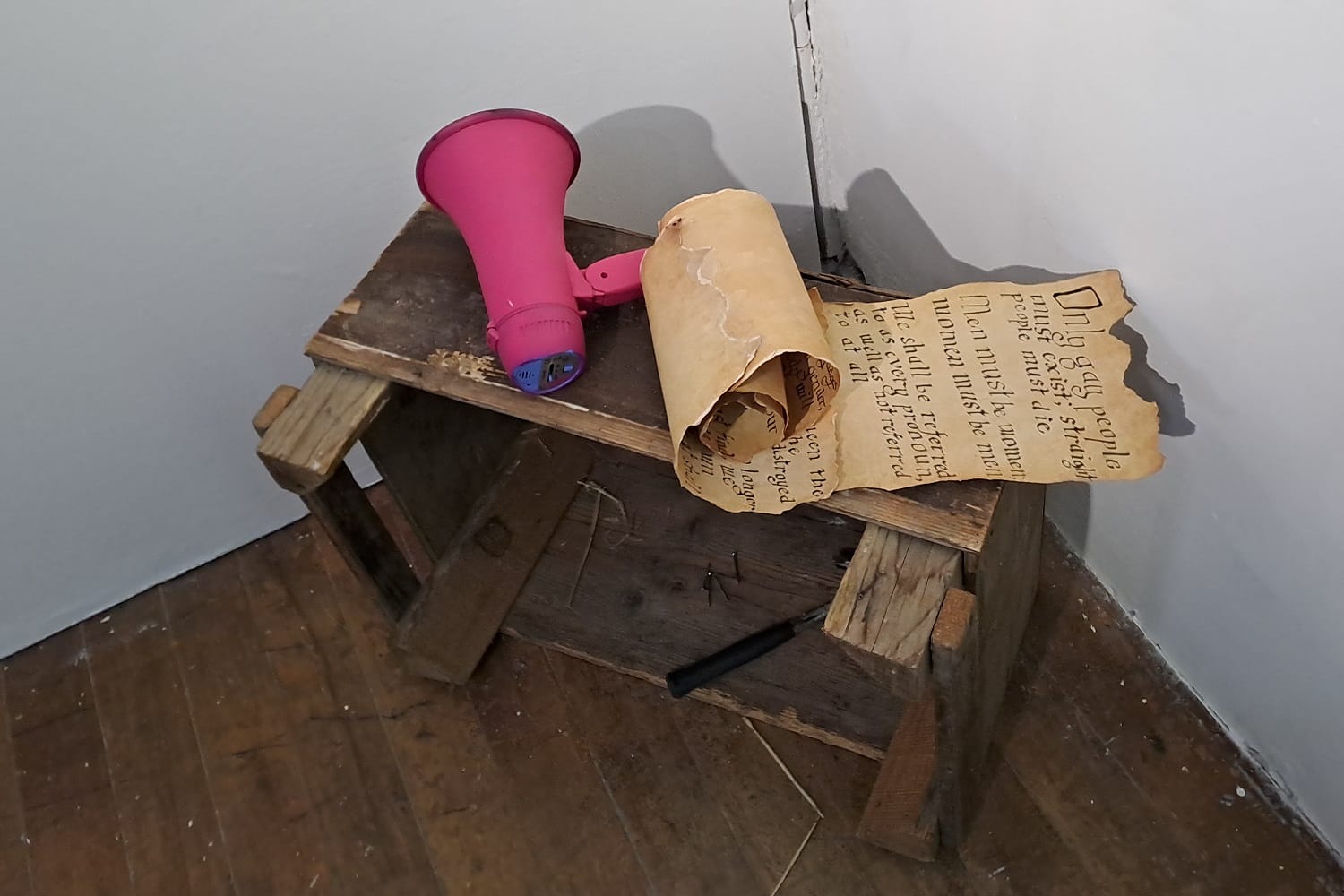

Silently, she crossed the room to a small wooden crate and took out a pink megaphone.

Wearing a straw cowboy hat, a white sleeveless frock and brown leather cowboy boots, Patel stepped up on her soapbox. And in a drawling Texan accent, she read from her manifesto, written out on a scroll.

She spoke at the top of her lungs, imitating an evangelical preacher, detailing a pilgrimage up to the Hellfire Club atop Montpelier Hill in Dublin’s south.

“And suddenly appeared before me a beautiful red cloud, the sound of faraway trumpets, and finally a beautiful monstrous creature appeared before me,” she said at the top of her lungs. “It was her, half-animal, half-human, our one most divine!”

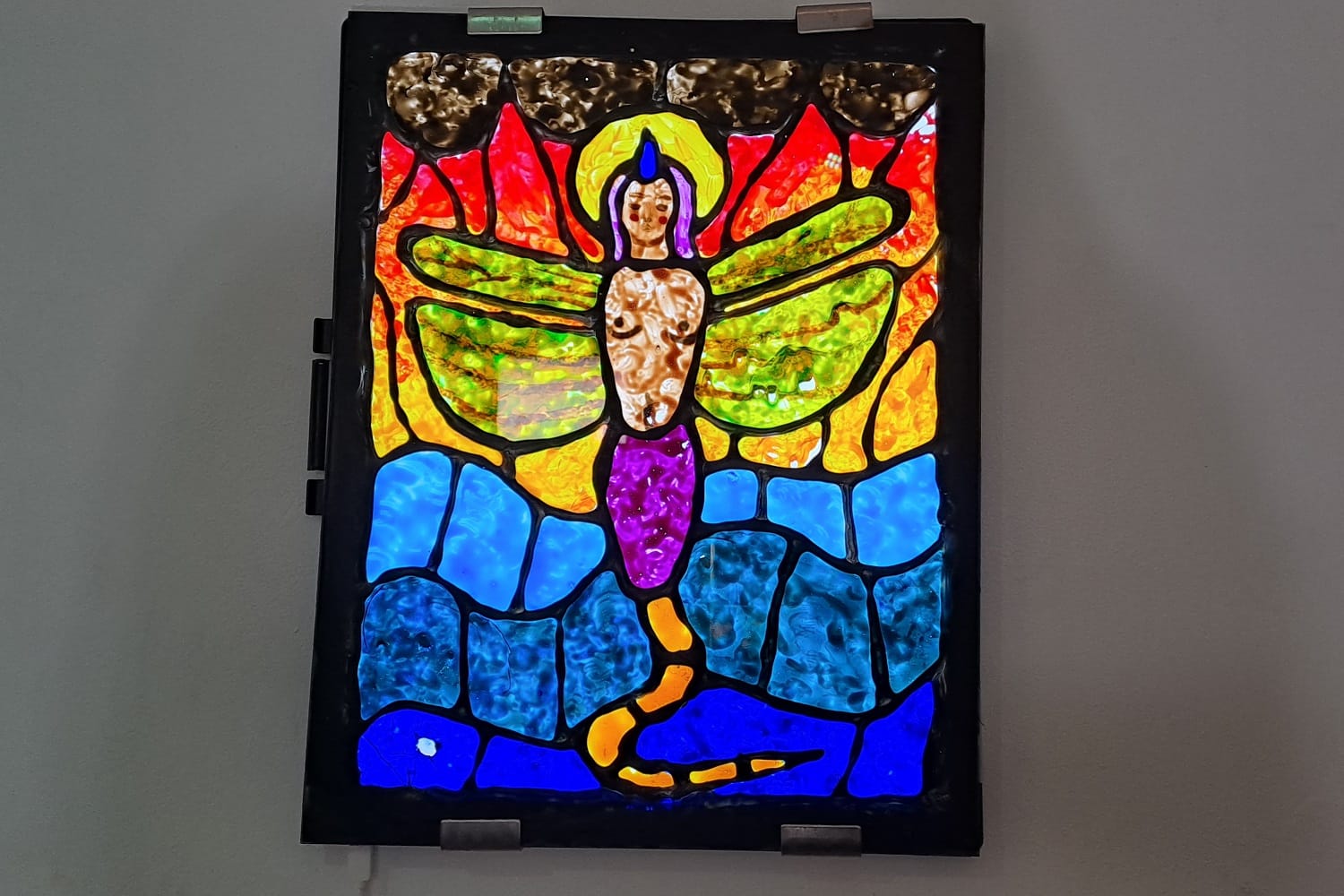

Patel’s fascination with such religious imagery stems from her childhood, she says.

With both Indian and Salvadoran heritage, she was born and raised Catholic in Los Angeles, California, she says. “I grew up with a lot of Catholic guilt and was always drawn to the Book of Revelations.”

The Bible had no shortage of visually striking scenes, she says, but Revelations was on another level entirely. “In its rich imagery it is very queer, with dragons, women on lions coming down from the sky. It is just beautiful.”

Patel’s first foray into performance was as a child actor, she says. “I was on a few kids’ shows as a back-up dancer, like on Yo Gabba Gabba!”

She pursued that for a few years and was always drawn to theatre. But, she says, her first serious step into the world of performance arts came when she moved to Dublin in 2018. “In college, I did a module on it, and got a chance to explore myself a bit.”

Performance art, she says, enabled her to express herself meaningfully, and the preacher character whom she devised for “Monsters of the Apocalypse” embodied that discovery. “She preaches to you about the end of conformity and to accept your true monstrous self.”

Patel first made a name for herself in Dublin by producing videos on TikTok, and to date has amassed more than 148,000 followers.

It was a by-product of the Covid lockdowns, she says. “But having to make everything as a video gave me a love for film.”

Last October, her filmmaking received recognition when she was awarded the 2022 RDS Taylor Art Award for her short film Eggshells.

Split into 12 parts, Eggshells revisits an incident in which Patel was assaulted and pelted with eggs. It’s explored through several characters, each of whom performs with an egg.

Her art is her means of processing traumatic ordeals of that nature, she says. “With things like that, it makes you not want to be yourself as much, but through this I can do what I want, feel how I want and be crazy.”

Eggshells is reminiscent of the camp and transgressive style of filmmaker John Waters, performance artist Day Magee says.

What is striking about Patel is the bravery in her artistry, says Magee. “She is performing around the northside of Dublin, presenting beautifully and flamboyantly, not just in her work, but her everyday life.”

Shooting Patel’s performances guerilla-style out in public spaces around the city is uncomfortable but deliberately so, says Murky Onyango, the cinematographer on both Eggshells and the short film which accompanies “Monsters of the Apocalypse”. There is an element of confrontation to the work.

“But we like that because it reverses the discomfort that we feel as people of colour with people looking at us,” Onyango says. “By making other people feel slightly that same way, it gives people a hint of our experience.”

Patel says it is about building empathy. “But what is difficult is asking on what level do I want to be absurd, and on what level do I want to still educate?”

Her fundamental desire is to build a sense of community from the work itself, she says. “I want the work to be a place for queer people to go, feel accepted and laugh, and for others to be open and understanding.”

Over the course of the lockdowns, everything became awful, she says. “We were so separated, and I feel like I get a lot more hate on the street because I look a certain way now.”

“We’ve lost a lot of that sense of community,” she says. “So I just want to bolster that or find it in some new way.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.