What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

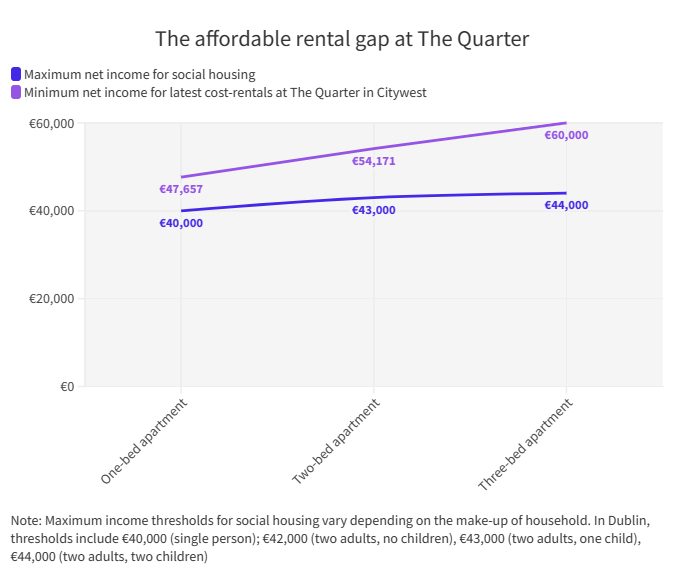

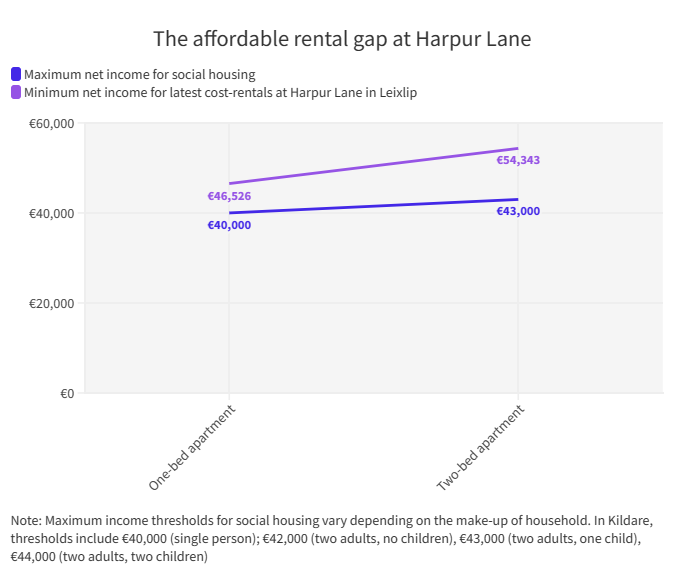

There’s a cohort earning too much for social housing, but too little to qualify for the Land Development Agency’s new cost-rental “affordable” housing schemes.

A look at the Land Development Agency’s latest “affordable” cost-rental homes suggests that some of the renters the model is supposed to be aimed at won’t qualify for them.

They’ll fall through the cracks, earning too much to qualify for a social home, but too little to qualify for these cost-rental homes.

People eyeing up a three-bed apartment in The Quarter at Citywest, for example, face a cost-rent of €1,750 a month, and so – given cost-renters can pay no more than 35 percent of their net income on rent – a minimum household net income of €60,000 a year.

Meanwhile, a household of two adults and two children would have to earn less than €44,000 net to qualify for a social home.

So households of this size, earning between €44,000 and €60,000 after tax, fall into a gap between these two government supports – and are left to fend for themselves in the private market.

“I think the cost rental model is in a real crisis,” says Eoin Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin TD and housing spokesperson.

For 30 years, policy experts were flagging that there were people whose housing needs couldn’t be met by social homes given income thresholds, or private rentals because they were too expensive, and arguing for an alternative, he said.

“Whether you call it affordable housing, cost-rental housing, intermediate housing, it doesn’t matter,” Ó Broin says. But “the problem right now is that cost-rental, on the basis of prices we’re seeing, still doesn’t meet those”.

The Land Development Agency (LDA) said last week that it will open soon for applications for 621 new cost-rental homes.

It listed four projects in the Dublin suburbs and Kildare: at Hansfield in Dublin 15, Citywest, Leixlip, and Kilternan. It’s the biggest bulk of cost-rental homes put out by the LDA, adding to other homes in Citywest and in Delgany in Wicklow.

When Daniel Cahalin applied for the cost-rental homes in Delgany, he hadn’t really clocked that there was a minimum household income to qualify, he says. “I’d presumed you had to be under a certain amount.”

But a while after his application, he got an email saying he hadn’t been successful. He didn’t earn enough, it said.

For him, it wasn’t that big a deal, he says. He and his wife had thought it wasn’t a great location for them really, and they weren’t under pressure to leave the place they were in.

Cahalin’s income at the time – which has since changed – also put him a whisker above the social housing threshold.

He wasn’t that conscious of that though, he says, because social housing wasn’t the kind of thing he had ever considered.

But Cahalin fell right into the gap between social housing and cost-rental “affordable” housing. “I’m very average,” he says, “surely there were other people like me.”

In July last year, Minister for Housing Darragh O’Brien announced that the government was increasing the net income thresholds for cost-rental homes. Rather than €53,000, it would be up to €66,000 in Dublin and €59,000 elsewhere.

“The increased thresholds recognise that prevailing rents in the private market have increased significantly in recent years and a large cohort of private renters are experiencing severe affordability challenges, particularly in Dublin,” said a department statement.

At issue, though, is whether the change was driven by a desire to serve more struggling renters – or to make the sums add up for homes delivered through the current cost-rental model, by clearing the way for those able to pay higher rents rather than finding a way to make them affordable for those who can’t.

To qualify for one of the LDA’s two-beds or three-beds in Citywest, or a 2-bed in Leixlip, renters would need a net household income higher than €53,000, the old ceiling for eligibility.

Three-bed duplexes in Delgany were advertised in November 2022 for €1,550 a month. But households needed a minimum annual net income of €53,143 – a figure that also would have meant the household earned too much at that time to qualify for cost-rental housing.

A spokesperson for the Department of Housing said that the decision to increase income limits for eligibility “was informed both by the analysis of Departmental officials and by the Department’s ongoing engagement with the range of Cost Rental providers”.

Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin TD and housing spokesperson, says that it is true that a household renting in the private-rental sector with an income of say, even €80,000 gross would struggle now.

“Therefore, sure there’s an argument for expanding it,” he said. “But that only makes sense if you also expand the overall provision of it.”

He says the motivation for expanding eligibility was actually that cost-rentals were coming in at too high a rate for many in the bracket they were originally meant for.

Asked about the risk of drift towards serving those at the higher end of the bracket for cost-rental, a spokesperson for the LDA pointed to houses it is also now offering in its latest phase at Parklands in City West.

Three-beds are €1,350 a month, so affordable to a household with a net income of €46,000 a year, the spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, “€46,000 is the upper limit of social housing qualification, hence the full range of household incomes are covered,” they said.

Within Dublin, €46,000 is the limit for households with two adults and four children. Smaller households have a lower limit.

Government statements about cost-rental homes and their affordability often point to how they have to be rented at least 25 percent lower than the market rate.

The LDA’s press release last week about the more than 600 new cost-rental homes makes the same case. The rents for these come in at 25 percent lower than market rents, it says.

However, tenants in nearby neighbourhoods may find that some of the advertised rents at the LDA projects are similar to their current private-market rents, and or more than they are paying.

For example, the LDA is advertising one-bedroom apartments on Harpur Lane in Leixlip for €1,357. The average one-bed rent in the area as of Q2 2023, according to the Residential Tenancies Board rent index, was €1,207.52.

When Daniel Cahalin applied to an earlier round of the LDA’s cost-rental homes in Delgany in Wicklow, the rent for two-beds was €20 less than the private rental that he and his family were already in.

“I think it was introduced as a mechanism for driving down private rental prices,” he says, but the Delgany ones seemed to him around the average price for the area. “Its not as if they were driving it down.”

That said they were nice new builds in a nice part of Wicklow, he says. “It would have been an attractive place for a lot of people.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Housing said that when assessing how rent levels in new cost-rentals relate to market rents, they consider comparable local properties, a task done by a qualified valuer.

“In the case of new build Cost Rental homes, this would mean reference to comparable new or recently developed homes in the area,” they said.

If policy is to reference market rents, then that comparison makes sense, says Mick Byrne, a housing researcher and assistant professor at University College Dublin. It should be rent-per-square-metre of the cost-rental to rent-per-square-metre of comparable new tenancies, he said.

“We’ve a real problem in Ireland that we are comparing averages of millions of different things mixed together and it just doesn’t mean anything,” he said.

After all, in most places the private rentals are rent-controlled with some longer tenants on much lower rent so there isn’t really a real “market rent” in that segment either, he said.

That said, in his view, how rents relate to market rents – which are hard to define and move all over the place – just shouldn’t come into considerations around cost-rental and affordability, he says.

“Instead, you should have some other way of limiting what the top costs would be that’s kind of independent and also that’s clearly defined,” he said.

Byrne says that one way to address the fear of an abandoned cohort just above the social housing threshold but often falling short on earnings under current rules would be, well, to change the rules.

Should the criteria be that tenants can’t spend more than 35 percent of their disposable income on rent to qualify? says Byrne. “In my view, no.”

He isn’t clear on the best way to judge if that was gone, he said, but maybe by just looking at the income after rent and assessing whether it would be enough for a household to live on sustainably, he says.

But cost-rental homes with high rents will favour better-off tenants, he said, and you could end up with a squeezed middle within the squeezed middle, given the affordability criteria.

“Without the affordability criteria in the mix, it wouldn’t necessarily be the case,” he said.

Letting people pay more of their income is one possible solution. Bringing down the costs of projects so that the rents at them are lower is another, given the rents in cost-rentals are determined by the cost of delivering and maintaining the homes.

The projects advertised by the LDA have been done under Project Tosaigh, under which the agency partners with private developers on developments that have planning permission but have stalled out because of financing constraints, say.

What costs are actually included in these LDA cost-rental projects is kind of unknown, says Byrne. “The key point would be whether or not the private-sector developer required and obtained a developer’s margin and what that percentage was.”

If the LDA has struck a deal to buy from a developer before they’ve even built it, it should bring down project costs, finance and risk, he said. Which means there isn’t really justification for a margin, he said.

“There needs to be a debate around what the costs in cost-rental are and the extent to which developers can include developer margins in the cost,” he said.

Austria has caps on the overall costs per square metre, Byrne said. A scheme that comes in higher isn’t eligible, he said. “What that means is that the contractors have to deliver within, and they can’t start inflating the costs.”

Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin TD, says that the idea of cost-rental is to strip away as much the private-sector profit that finds its way into rent-setting in a private-sector rental.

The problem is cost rental really only works if you’re delivering the units yourself, he says. “If you’re completely dependent on private developers through forward-purchase agreements or turnkeys, you’re taking on a set of costs that cost-rental is supposed to avoid.”

A spokesperson for the LDA said that it performs a “value for money” assessment which looks at the costs of the development and makes sure the price paid is fair, “recognising that a builder cannot and will not build without some element of margin included”.

“However, the analysis performed by the LDA ensures that the profit element is not outsized,” they said.

Its next round of Project Tosaigh is based on a competitive process, they said. “Which involves pricing tension amongst housebuilders, which further ensures the most competitive deal possible is obtained by the LDA.”

Ó Broin says there are several ways that the cost-rentals could be made affordable for those right above the social-housing threshold, for whom they were originally intended.

Financing could be stretched over a longer period than the 40 years in the legislation, with delivery through councils, who can access the cheapest finance, he said.

You could also look at the government giving some kind of soft loan, that would get paid back after any other finance has been, he said. “So they’re your parameters.”

Another option if families living on €40,000 or €50,000 can’t get into cost-rental would be to further raise the threshold for social housing, he says.

“That gap can’t exist. But it absolutely has existed and it’s getting worse,” Ó Broin says.

Debate around further measures to bring down cost-rents relates to a much bigger policy question though, Byrne says.

Should the priority be to contain rents in cost-rental immediately so that they are as affordable as possible for the tenants moving in today or do longer-term considerations supersede that? he asks.

If lower rents rely on government subsidies then that pushes more costs onto the state and, if it costs more, it makes it more difficult to scale-up supply, he says.

“That’s where the policy thing comes in and you have to say, maybe we can live with the high rents, because we think that the long-term value of having a large segment of non-market housing that is stable in terms of rent and in terms of security will make Dublin a better place with overall better housing outcomes, looked at over the long-term,” he says.

Says Byrne: “I think that is a much more difficult to answer than it might first appear.”

A spokesperson for the LDA pointed to long-term benefits of a scaled-up cost-rental sector.

“As more cost rental properties are made available, there will ultimately be knock-on impact on rents in the private market, in that private market rents will be moderated,” they said.

That’s definitely a consideration, says Ó Broin, but there’s also the present. “The problem is that: where are the rentals now for the folks on €45,000, €50, €55,000?”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.