In Dublin 15, councillors want to name a park for a local cycling legend

They agreed a motion, recently, to ask Fingal’s naming committee to honour Bertie Donnelly. But are park renamings even possible these days?

Some local residents want to see the old St Donagh’s holy well in Donaghmede memorialised in some way. Damien Dempsey is one of them.

Damien Dempsey stands on Holywell Road, drawing in a deep breath as he stares out over the green where he spent much of his youth.

As the name suggests, there was once a holy well nearby, known as St Donagh’s Well.

“It was a mad spot growing up. Amazing people. But sometimes it was crazy, as a kid,”says Dempsey, the beloved bard of Donaghmede.

On his classic, autobiographical coming-of-age ballad “Factories”, Dempsey sang: “From the corner of Holywell Road, see the sunset over St Donagh’s … see the sunset over the world.”

Did the songwriter’s younger self know that when he stood in that very spot, he was far from the first pilgrim to stand there contemplating his place on this earth?

“I was more worried about not getting hopped on, I suppose,” he said. “But yeah, I always felt there was something spiritual around here.”

While holy wells remain dotted across the Irish landscape, in urban centres like Dublin, most have disappeared as housing developments have sprung up on every available plot.

But Dublin City Council historian-in-residence Katie Blackwood has been highlighting the former sites of holy wells across north Dublin at a series of talks – including St Donagh’s Well – including in Marino in March.

Once, holy wells like St Donagh’s were important meeting places for communities, revered as sacred connectors between the material and the spiritual realms, says Blackwood. Over 130 have been identified in Dublin.

They serve now as a reminder of pre-Christian pagan roots, when divinity was found in nature. The water from these naturally occurring holes in the ground was celebrated for its magical, medicinal power, says Blackwood.

While some wells had a more general use, others were known for curing particular illnesses like eye diseases, toothaches, headaches, backaches, rashes, ulcers, infertility, whooping coughs and rheumatism.

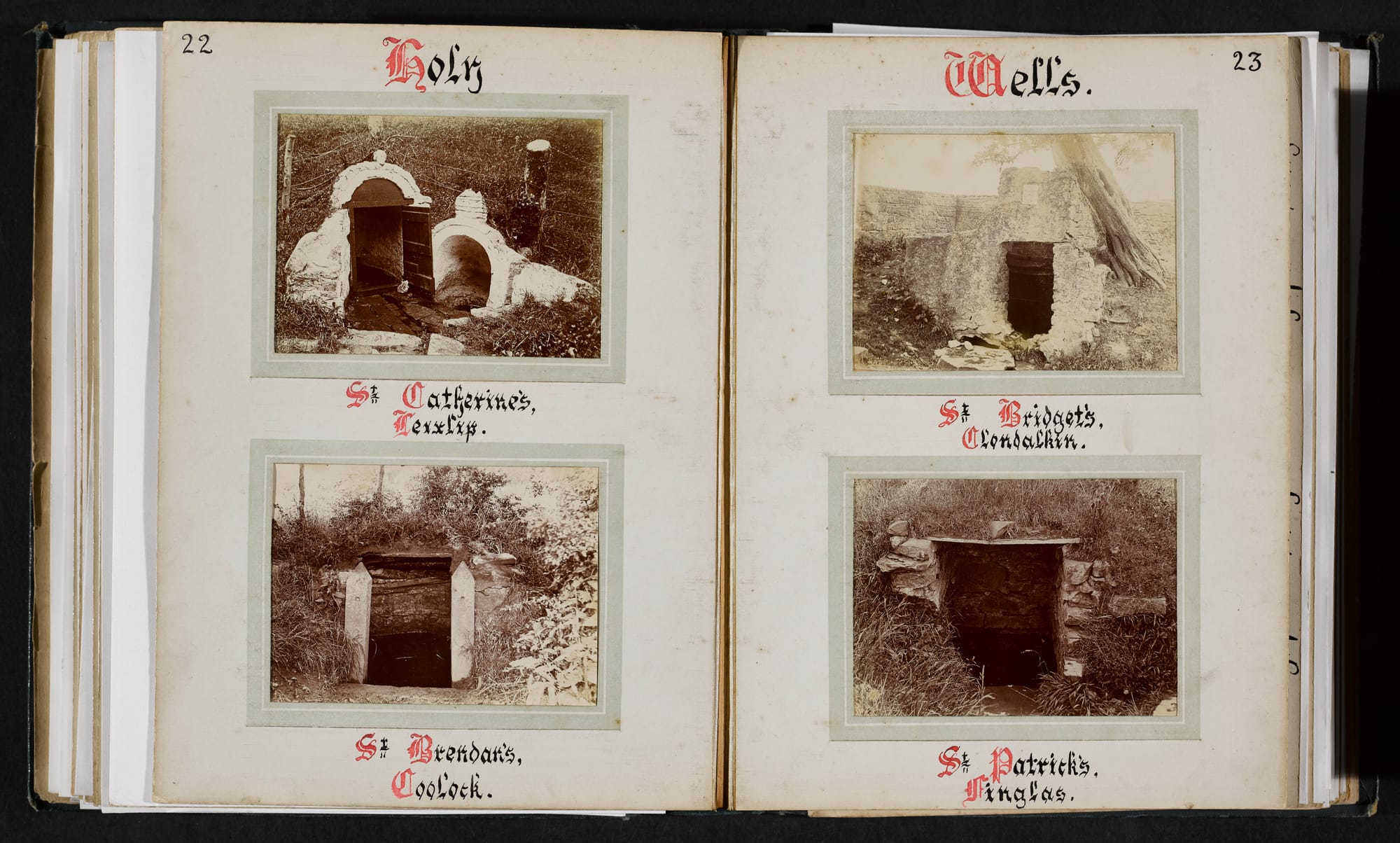

St Brendan’s Well in Coolock, is a stone’s throw from the gates of St John the Evangelist Anglican Church, alongside the narrow Santry River.

“Water worship is a universal feature of prehistoric societies because of its life-giving qualities,” says Blackwood, the historian-in-residence for the council’s North Central Area.

Locals gathered at the wells, often on patron saints’ days or “pattern days”, and performed rituals like “rounding the well”. They would move clockwise around the well a certain number of times, often on their knees.

They would say prayers and drink the water. Then, often they would throw a big party.

“As Christianity was introduced on the island, holy wells and their traditions were subsumed and adapted by the new religion,” Blackwood says. “Holy wells that were already in use were dedicated to Irish saints. St Patrick and St Brigid the most common.”

In Coolock, the physical well at St Brendan’s is gone now but the spot is marked by a hawthorn tree, a fairy tree, another natural feature once thought to possess special powers. Fairy trees and holy wells often come hand in hand, says Blackwood.

A man on a Massey Ferguson is making his way up and down the riverbank, near St Brendan’s Well, cutting the grass.

It’s Hugh Doyle, who is 46 years working with Dublin City Council Parks Department, he says. The well was already filled in by the time he started the job in 1979, Doyle says.

“I know people who remember it. I don’t myself. But I do know not to damage that fairy tree, whatever I do. God knows what might happen to me,” he says, with a glint in his eye.

Similar to fairy trees, treating holy wells badly was thought to bring grave misfortune, Blackwood says.

“Damaging a holy well is linked to stories of cattle dying and even people’s houses burning down,” Blackwood said.

Veering away from north Dublin for a moment, Tallaght native Daithí Turner, who now lives in Easkey in Co. Sligo, documented a curious image.

There is an ancient dolmen tomb in the locality known as the Giant’s Griddle, and the stone structure is flanked by a fairy tree.

A fire broke out in 2011, raging through a spruce plantation up the hill toward the tomb until it stopped, at the foot of the fairy tree.

The tree and the tomb remained untouched.

It’s not only holy wells and fairy trees dotted across north Dublin, either.

Not far from St Brendan’s Well sits the Cadbury factory, and just inside that compound, Blackwood points out a mount covered in trees.

It is an ancient burial mound, of which little is known, Blackwood says. It was probably connected to the well and fairy tree, she says.

Archaeologist Michael Stanley wrote about the mound in a 2011 Archaeology Ireland article, “Chocolate and Community Archaeology”.

“When I first mentioned the Cadbury mound to my Auntie Bridie, she recounted a story from the 1950s about a man suffering a heart attack while felling one of the trees that grew upon it,” he wrote. “This was attributed to the fairies taking retribution.”

He also recounts a story of a man who dug into the mound and broke his leg. And another version of that story, about a “strange face” that appears under the branches of one of the trees at Halloween.

It’s “thought to be that of a man who attempted to dig the mound and went missing that night”, he writes. “ That these ‘suburban myths’ persist reveals much about local people’s regard for the past.”

Another account, seemingly referring to the mound at Cadbury, comes from a hand-written story by a school child in the 1930s, preserved in the National Folklore Collection’s Schools Collection.

“There are several trees and hawthorn bushes around it. It is said to be a fairy moat and a crock of gold was buried there about eighty years ago,” he writes.

A group of four young men went up to the mound to dig into it, and “one of them brought his pet dog as there was a life to be lost in the digging”. Eventually struck the crock, the child writes.

“Instantly the dog howled terribly. The men looked around and could not see him. Then they gathered up their picks and shovels and turned away. But the little dog was never seen since, nor did anyone ever look for the crock afterwards,” he writes.

A spokesperson for Mondelez International, parent company of Cadbury, said the company are “honoured to be the custodians of this ancient treasure which has inspired so much local folklore”.

“We are committed to safeguarding this important monument so that future generations continue to be intrigued by its mystery,” he said.

St Donagh’s Well, in Donaghmede, was on a green between St Donagh’s Road and Holywell Road, along what was known as the Kilbarrack Stream or the Donagh Waters.

Samuel Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, published in 1837, says the well was visited “on St John’s Eve by poor sick people”, who rubbed themselves against the walls of the well and then washed in another one nearby.

St John’s Eve, 23 June, is derived from the pagan summer solstice festival, and has strong traditions associated with fire and fertility. Communities would gather by the wells and light bonfires to guide the sun and usher in a good harvest.

Young men would apparently demonstrate their bravery and prowess by jumping through the flames. Young women would also partake, so that they would be blessed with children.

“People really used it as an excuse for a good party,” says Blackwood. “It can be easy to think of people from the past as totally different, alien almost, but it really humanises them when you realise that they, like us, were always just looking for an excuse to throw a party.”

The St Donagh’s well was still there in 1958 when folklorist Caoimhín Ó Danachair compiled his list of holy wells in Dublin, but was gone by 1970.

The stream was culverted in the 1970s and 1980s, according to locals. Now, there’s no sign of the former well.

But there is a large black circle burned into the grass. Young people apparently still gather there for a bonfire and their own form of revelry on the spot.

Blackwood pointed out letters to the Irish Press and the Irish Times by P. Healy of the Dublin Civic Trust in 1975, expressing his disappointment that the well was not marked for posterity.

“The site is now an open space south of the shopping centre and the well could have been preserved as a centrepiece of this area,” he wrote.

Still today, some local residents want to see the old St Donagh’s Well memorialised in some way. Damien Dempsey is one of them.

“I’d love for it to be marked,” Dempsey says. “I’d like to head down and spend time there once in a while. To remember our ancestors, to commune with them and say hello to the Great Spirit.”

He had a bad cut on his thumb. He’d had a disagreement with a potato peeler the day before, and the peeler won, he says.

Even if the well was still there though, there’d have been no use washing his wound in it, Dempsey says. “That well was known for helping eyesight problems,” he says.

Dempsey’s work has always been marked by a sense of spiritual longing, and a passion for history.

“I never will forget the suffering that my people went through in my country and overseas,” he sang on “Negative Vibes”, from the same Seize the Day album that “Factories” appeared on in 2003.

At the site of St Donagh’s Well on Monday, Dempsey says there was “a huge amount of creativity in this small little patch”.

“Les Enfants, Humanzi, LiR and myself all came from around the same road and all had record deals. The performance artist Growler is from my road too, she’s brilliant,” he says.

“We would always joke that there was something in the water around here. Maybe we were right. There is something magic around the Holywell,” he says.

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.