What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

State-funded education and training courses for the unemployed have a reputation as time-wasting paths to nowhere. Maybe this one is different though.

In his three years on the dole since secondary school, Alex Fitzsimons has sampled a couple of FAS courses. First stop was server maintenance. Later came catering.

After that, he tried to set up a baking business, and went around businesses and shops in Clondalkin, where he’s from, hawking cakes, muffins, brownies and cookies. But it didn’t work out.

“I didn’t have the skills or the know-how to set up something myself,” Fitzsimons said last Wednesday

That’s the kind of story that you expect to hear about state-funded education and training courses for the unemployed. Rightly or wrongly, they don’t have the best reputations.

At best, they’re seen as training courses in basic skills that could lead to further education or a scarce entry-level job. At worst, a slapdash way to get out-of-work people out of the house, a way of ensuring they are doing something, anything.

Or take the recent research into the Back to Education Allowance (BTEA), which provides entry for the unemployed into second- and third-level education.

A recent ESRI report found that jobseekers who started the BTEA scheme in 2008 were less likely to have found employment four and six years later than those who didn’t.

Those are poor and puzzling results, especially given that the Department of Social Protection’s spending on the scheme more than trebled, from €64 million in 2007 to €199.5 million in 2012, according to the report.

The report doesn’t get into the reason the BTEA scheme didn’t seem to get people into employment and help them stay there. But Momentum might offer a clue.

One reason might be a lack of connection between the courses people were taking, and the job advertisements they found once they finished.

Enter Momentum, a scheme backed by Solas that helps the long-term unemployed grab at jobs in areas beyond cleaning or jabbing at cash registers, in areas where there is growth.

Unlike BTEA, Momentum’s aim is to provide people with the skills in growth areas that are in actual need of skilled employees. That’s the idea, anyway. One course, in particular, under the scheme would almost make you wish you were unemployed just so you could go for it.

Pulse College’s Self-Employment Course in Gaming and Interactive Technologies for long-term unemployed is a 33-week course aimed at transforming unemployed gaming enthusiasts into game developers and entrepreneurs.

The participants will learn the skills to not only make their own video games but also to build their own gaming business, from an original concept into a real venture.

“There was great interest in the course,” says Sarah Walsh, Momentum project manager at Pulse College. “And there was an excitement for participants to know that this is a great opportunity they’re being offered.”

We are sitting in the library of the Halston Street campus of Pulse College. More a chill-out area for students than a library, it is a small, bright room with a coffee table and comfortable seats, wooden table and chairs and a bookcase full of books on gaming, from design to coding.

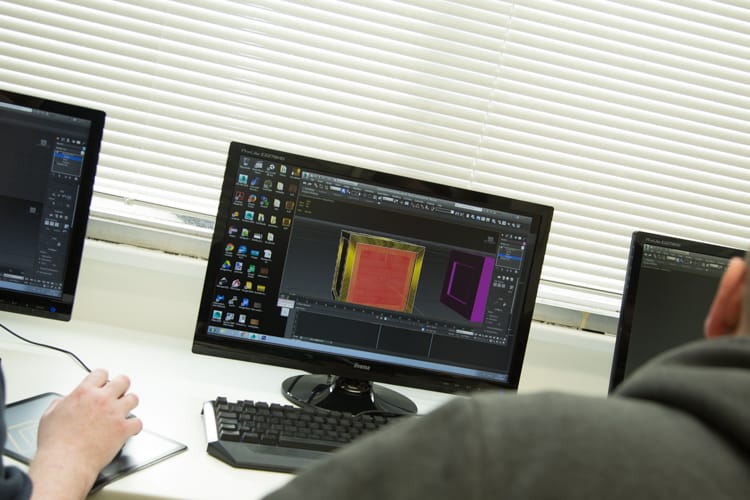

Just up the corridor, off which are several computer labs and a couple of offices, the 44 students are in class, brainstorming ideas for a potential video game.

It’s only their second week on the gaming course, but their enthusiasm has already been noted, Walsh says.

“Keeping their motivation up is an important aspect, particularly for these students, as they’re long-term unemployed and they mightn’t have been in a classroom environment for many years,” she says.

Most of the candidates have some form of gaming background, Walsh says. The one trait they all share is a keen interest in games. So sustaining motivation shouldn’t be an issue.

It certainly doesn’t seem to be for Brendan Boeger and Alex Fitzsimons, who catch up with me in the library after their brainstorming session. Both are still giddy from it.

“Everyone was throwing ideas at the board,” Boeger says, “and I’ve no idea how to explain what we came up with.”

The group had to come up with one idea for a game.

“We need one idea,” Boeger says. “What’s the setting? Space. Right, okay. Now we need a protagonist: sheep. Okay, we have space and we have sheep. Now we need an enemy: donkeys.”

Fitzsimons laughs heartily.

“We need to write the story of that,” Boeger says.

Its early days, but both are clearly enjoying the course so far and excited about what’s to come.

Originally from Leitrim, Boeger, 26, has been on the dole for over five years, ever since he left college at Carlow IT, where he was studying computer-games development. He had to leave after second year because he didn’t make the cut to get into third year, he says.

Having failed to find work in Carlow, he moved to Dublin to try get into a graphic design course he was interested in. “I didn’t have the skills to get accepted, even though it was an introductory course,” he says.

He did, however, complete courses in 3D animation and computer repairs, and scored a place on a web-development Momentum programme. But when he went looking for work he kept coming up against the same barrier: lack of experience.

“There are a lot of gaming companies here, but you need experience to get work, you need work to get experience; it’s catch-22,” Brendan says.

Fitzsimons, 21, met the exact same obstacle.

“Even when you get the interview, you’re told, ‘You need more experience,’” he says. “How am I to get experience without a job?” he says.

What he did have was a huge interest in gaming and how video games worked, particularly why they sometimes didn’t work in the way they should.

“Say there’s a boundary around here but there’s one little bit in the wall there and for some reason you can go through it. I always wondered why is the coding not working there,” he says.

The opportunity to get to the bottom of such conundrums presented itself a couple of months back when he walked into his local social welfare office and spotted a poster advertising the gaming and entrepreneurship course at Pulse College.

Both were surprised that Pulse College was offering a course like this for free.

The education faculty of Windmill Lane Recording Studios, Pulse has been specialising in creative-media education for 20 years and boasts Oscar and Grammy winners among its alumni.

Boeger says he was looking at a one-year animation course at Pulse College a couple of years ago. But at €6,000, it was too expensive.

Walsh, the project manager, says that a course like the Momentum one being provided would cost somewhere in the region of €7,000.

Given the recent growth in the global and domestic gaming industries, it’s easy to understand why. So far this year, total global games revenue was $91 billion dollars, according to report by games marketing research company Newzoo. Ireland ranked 37th out of 100 countries, with just under $176 million of that.

There was a 292 percent increase between 2009 and 2012 in the number of games developers in Ireland, according to a 2012 survey published on gamesdevelopers.ie. Jobs in the industry increased by 91 percent in the same period, from 1,469 to just over 2,800, the report said.

It’s an industry Mick Rochford, project-management lecturer at Pulse College, wanted a piece of.

Five years ago, he knew next to nothing about game development. He was the CEO of a construction company up until 2010, “when the shit hit the fan,” he says

He’d had an interest in games from an early age, and he decided it was industry he wanted to delve into. “I knew it was something that I’d get up in the morning and enjoy going into it,” he says.

With no formal training in developing games, he transferred the skills of project management he’d used in construction to gaming.

“I gathered the team, the expertise, and I immersed myself in that world for a year to synchronise meself with a brand-new industry,” he says. “Just took a chance and went from there.”

That first year, he got together with a games developer and started making simple side-scrolling platform games.

The first game they made was Joe Vs Banker. “It was a game where you get retribution on your banker who’s coming to capture Joe’s house with a bailiff and a dog. So, it was tapping into that anger-against-banks vibe going on at the time.”

In 2013, Joe Vs Banker was nominated for Game of the Year at the Irish Game Developer Awards, losing out to League of Legends.

The following year, he won an Appy award for Best Children’s Game with Planet Munchie, a game that “encourages, records and rewards children for becoming healthier”.

The game, developed under his company Mick Rock Productions, is due for general release at the end of this month.

His students at Pulse will be doing well to follow in his footsteps.

Last year was Rochford’s first to lecture at the college, he says. “This year I’m heading up the games side and the idea-generation and project-management from brainstorm to completion of the game.”

“It’s good to teach something that you’re passionate about, number one, but also something where you’ve been through everything, jumped through the hoops, looked for finance, etcetera.”

This is something both Boeger and Fitzsimons cited as a real benefit of the course: the fact that they’re being taught by lecturers who have worked and been successful in the industry.

One student keen to emulate his teacher’s success, and who has already made steps to do so, is Colm Leonard from Rush, County Dublin.

Leonard tried to become a mechanic after secondary school, but colour blindness stopped him. He wasn’t able to get into Carlow IT to study Computer Games, either. So the burly but affable 28-year-old fell into various jobs in farming and construction.

More recently, it’s been security. Two and a half years ago, though, he was forced out of work with a slipped disc and nerve damage in his back. To this day, he doesn’t know how it happened, but it still causes him pain.

He looks back on this now as a fortunate event, because it led him down the path of his true passion: making games.

Like most gamers, his interest in games was formed at an early age. But Leonard also possessed a penchant for problem solving.

“I enjoy picking stuff up and fixing things, solving problems, fixing computers,” he says.

He says he spent about six months “whingeing” about his back problems before he got down to the business of teaching himself how to code. He did this for two years, he says, most days, learning how to code.

“Then three four months ago, I gave myself a kick, a deadline to make a game,” he says.

Bounce.ie was made in two weeks. The game involves getting a physics ball over obstacles of spikes by tapping the screen of your phone. “It was made purely to show I could finish with a deadline, and stick to it,” he says.

After that, Leonard gave himself two weeks to come up with another game. He did. It’s called Lancelot.

Again, he kept the game simple: a man on a horse hitting targets and jumping over obstacles. It was more for testing, he says, and getting the developer page on the Google Play store.

Leonard is now working on a more ambitious Rogue-like strategy game for the PC, which doesn’t have a name at the minute but is taking shape.

He’d applied for the course at Pulse College a couple of months back and only found out he was accepted a few days before it started.

It came in the nick of time. He was about a week away from filing all the papers for his own gaming start-up, which would have taken him off the dole and excluded him from the course.

“I was delighted to find out I’d got on to it,” he says.

This is Pulse College’s second Momentum programme in gaming.

The first was run between 2012 and 2013, but was slightly different in that its aim was to teach students the skills to develop games to work in the industry, rather than train them to be gaming entrepreneurs.

Rob Kelly, 39, is a graduate of that course and is now working out of Pulse College’s incubation office, where’s he’s adding the finishing touches to his game, Conkers, which will be released before Christmas.

The game will be aimed at the casual gamer, and, as its name suggests, is loosely based on the real-life game of conkers.

You use your conker to fire at objects like nuts and berries, “but you also need to be strategic or all your conkers will break,” he says.

Kelly, who came from a film-production and directing background, had been out of work for two years before starting the course.

He wasn’t what you’d call a “gamer”. The class gave him a harmless bit of stick about this fact, working out that the last game he’d played, Half-Life, was about 15 years old.

But he did have an interest in 3D technology and animation, having studied the latter in Ballyfermot College of Further Education in the mid ’90s.

A few weeks into the course, Kelly was hooked; he loved the creative aspect of game development and game design. He came to see games as an exciting medium through which to tell stories.

“To tell a story in animation and film would take a massive crew and a lot of time, whereas two people can make a game in a relative short space of time and develop these big stories you couldn’t normally develop without a big budget and a large crew,” he says.

Now, Kelly seems to be on track to realising his goal of “setting up a little studio, developing our first title and going on from there”.

Colm Leonard applied to the previous Momentum course, but because he hadn’t been on the dole for 12 months or more, he wasn’t eligible, “which is a bit ridiculous,” he says.

“Telling someone that they can’t do something until they’re out of work long enough to do it won’t motivate them,” he says.

Boeger and Fitzsimons agree; they don’t see the point in excluding people who’d be interested in such a course on the basis that they’re not out of employment long enough.

“Why have them sitting there twiddling their thumbs, doing jack shit, when they could be doing a course to get them off the dole?” Boeger says.

Adeline Meaghar, press officer at the Department of Education and Skills, which funds the Momentum scheme, said the programme was specifically designed for the long-term unemployed, so that they could gain in-demand skills in sectors of the economy where there are job opportunities.

“There are a range of other education and training opportunities available for unemployed people, but it is important to set aside some resources and design a response to meet the specific needs of long-term unemployed people,” she said.

It’s probably a good thing that Leonard wasn’t eligible for the last Momentum course at Pulse College, though, because the current one, with its start-up bent, seems more suited to him. In fact, it couldn’t be a better fit.

He’s already registered his games company name, IndiEire, and he has big plans for it. Eventually, he wants to develop console games on the scale of Grand Theft Auto.

“I like games that give players the freedom to do what they want in the game,” he says. “That’s the point I want to get up to. And I will.”

Leonard wants IndiEire to be more than just a games developer.

He wants it to be a hub open to people who have a real interest in games, who mightn’t have had the opportunity to pursue a career in the industry.

“It’s hard to get into business,” he says. “There are a lot of small games companies out there, but they won’t necessarily take you in and train you.”

“I want to try get big enough that I can take on people with the passion, even if they don’t have the skill, to have a little hub, bring people in, let them do a day, pick people out of that, see if I can help them,” he says.

Two weeks into the Momentum course, he already feels that by the end of the 33 weeks, he’ll be a good deal closer to achieving this goal.

Walsh, the project manager, says there may be one or two in the course who don’t want to set up their own businesses, but want to work for a games company, and they will have the skills and will have made connections to do that.

But it’s not inconceivable that with the rich pool of gaming talent on offer at the college, the next big games studio could come out of this course, she says.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.