What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Redrawing Dublin discover the tastes of Union 8 in Kilmainham, where the view leads to a point-by-point demolition of official excuses for dereliction.

In a new series, Redrawing Dublin are looking at some of the inner city’s great restaurants, and the challenges facing their neighbourhoods. You can read about their mission here.

It is week two in our Feeding Regeneration series and we have already broken our first and only rule. We decided (were forced?) to leave our self-imposed “inner-city” boundary.

Having reviewed Fish Shop in Dublin 7 last week, we moved to the Southside this week, but searched in vain for an interesting choice of an evening meal in the Liberties. (We welcome your suggestions for next time.)

Instead, on the advice of Liberties locals, we opted for Union 8 in Kilmainham.

Apparently, it is the sister restaurant of Catch 22, located off Grafton Street.

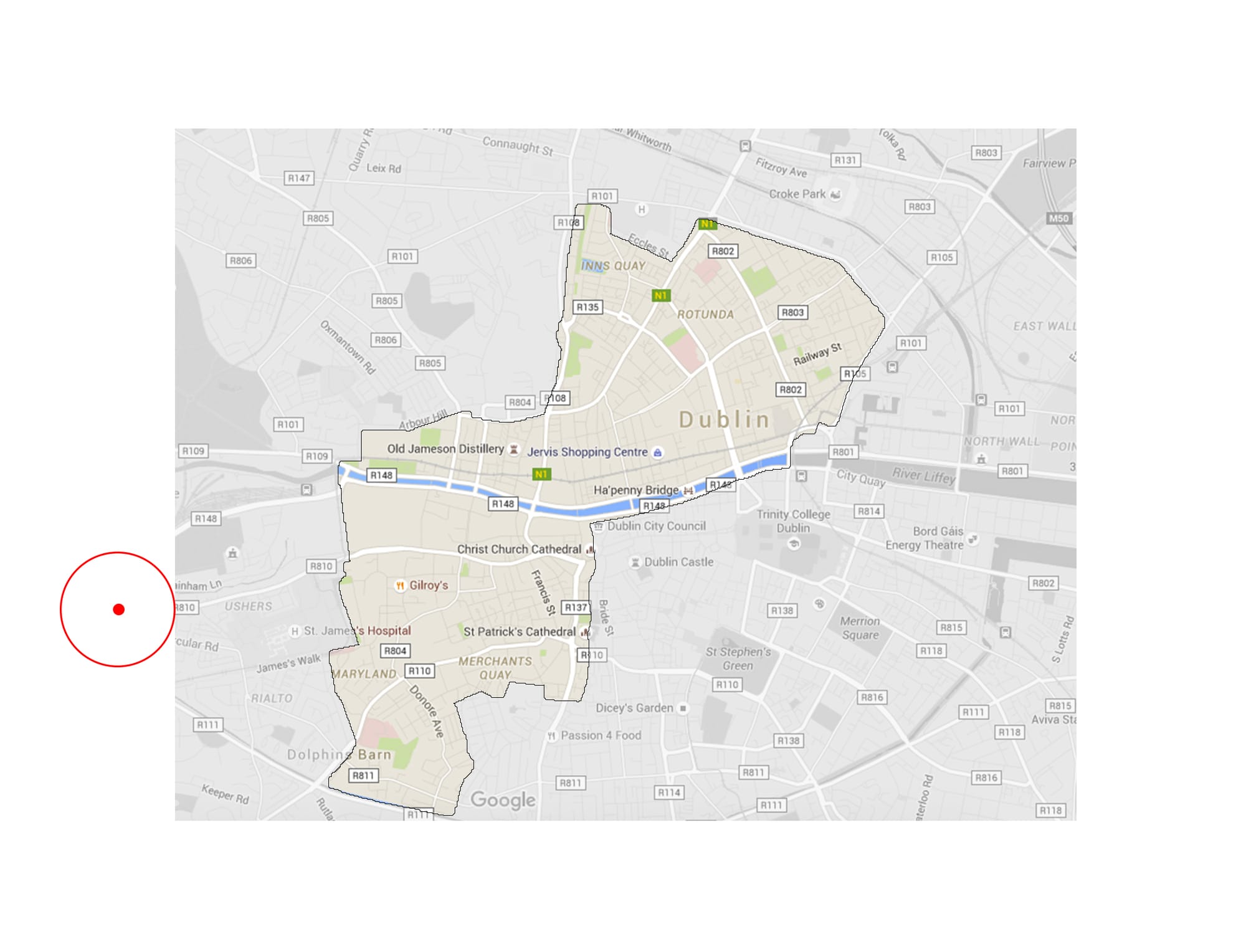

Union 8 lies just west of our inner city boundary (see map), but the local inner-suburban area pretty much qualifies for a Feeding Regeneration review; the neighbourhood is undergoing rapid, and, for the most part, positive regeneration.

Union 8 seems popular. Booking a table for two for Friday dinner proved impossible, even when calling a few days earlier. Surely a good sign. We decided not to give up and booked a late brunch on Saturday.

The restaurant is in an inspired, if risky, spot. At the busy intersection of Emmet Road and the South Circular Road, it occupies a large corner site.

With vast, in-your-face glazing that runs around two sides of the restaurant, and adjustable canopies, which opened and closed for no apparent reason, the restaurant makes a bold and wonderful statement. Physically at least, this is a proud addition to the inner-suburb of Kilmainham-Inchicore.

The name, Union 8, and indeed the overall first impression, exudes a vaguely American style or vibe, reminiscent of a New York bar-restaurant. In the restaurant’s own words, this is a “contemporary neighbourhood Eatery”.

The name, according to the restaurant’s website, “reflects our goal – to become the hub and focal point of our community & for those from further afield! We also chose it because of our location (union of roads) and our belief as to what a truly local restaurant should be (union of people).”

So full marks for regeneration ambition.

When we arrived, the place was fairly empty, although it was admittedly a late brunch. And empty can mean good, attentive service.

The restaurant’s interior includes an open kitchen and vintage styled colorful furniture, it has a warmth that invites you to come in sit and relax. It is rather beautiful.

We started out at the table in the corner, in part to get a good view of what was happening in the restaurant and open kitchen. Bad choice. The acoustics weren’t great, and the views weren’t what we wanted after all.

We asked to be moved to a table closer to the entrance, a table with a view of the heavy traffic outside. Our jolly, young waiter dutifully obliged. Good choice.

Union 8’s extensive wall of glass and corner location allow for fascinating views of the gritty location. It is strangely inspiring to look out of these vast windows.

On one side, a depressing vacant site. On another, a petrol station.

It is a busy and banal junction, yet it was captivating to watch the world go by from inside this chic eatery. Another restaurant might have obscured the view, introverted itself, but the designer of this one was clever.

Union 8’s isn’t the typical Dublin brunch menu, which can be a bit repetitive. We went for the superfood salad with goji, quinoa, goat’s curd, organic leaves and seeds, €9.95, and the fish and chips: beer batter, tartare sauce, €12.50. For sides, we chose the green salad (€3) and the ruby slaw (€3).

The presentation of both dishes was superb.

The fish came in an evenly golden-brown deep-fried tempura, thin and airy. The plaice was exquisite. The chunky chips were in partial skin, which seems to be the fashion, and came in one of those little metal baskets. The tartare sauce was infused with the delightful flavor and texture of nicely sized chopped pickles.

The superfood salad was a joy, all manner of vibrant colours: purple, a riot of greens, fire red from fresh goji berries — when do you ever get fresh goji berries in Dublin? — and white from the goat cheese. The brown quinoa hidden under the endive leaves was served simply, without too much seasoning; it was understated and fresh.

There is, however, a “but”. This superfood salad, super as it was to look at and to taste, was simply not enough as a main course, not even for a brunch menu. Luckily, we ordered sides.

The ruby slaw – red cabbage with plenty of mayonnaise – was, again, a beautiful color, and beautifully presented. It could have benefited from a kick of something else, to take the flavor and texture out of its comfort zone. Caraway seeds perhaps.

The green salad was a pleasant surprise. Too often, green salad in Dublin means a lettuce leaf and an additional green leaf if you are lucky. This salad had a huge variety of crunchy green and purple leafs.

The dessert menu, unfortunately, was disappointing. Most of the options were suited to breakfast or afternoon tea – more a pastry listing than a dessert menu. More options would have been welcome.

We chose to share the selection of homemade ice creams (€5), the most creative dessert on the menu. The two scoops of vanilla and two scoops of salted caramel came with two raspberries and two blueberries.

When we eventually asked for the bill, the all-too-attentive waiter disappeared for 10-15 minutes. We asked the host for the bill.

So one small piece of advice: the service perhaps should be less attentive and more effective, less over-the-top nice and more responsive when needed.

A very minor complaint. We left with smiles on our faces.

Union 8 is a great contribution to the area. If you don’t live right next to it, it’s a great excuse to walk the length of the gardens from IMMA.

Overall, our experience was impressive. Union 8 substantially raises the bar on cool and wonderful dining in Dublin’s inner suburbs. This place has phenomenal character.

Our local regeneration challenge for Union 8 is directly across the road. It’s dereliction, or what we would class as a derelict site, to be precise.

The issue is not the presence of this site, but the fact that the site is not designated derelict under the Derelict Site Act. This isn’t geeky planning stuff, it’s hugely important to the economy and health of the city.

Derelict sites not officially designated derelict seems to be an all-too-common reality across the inner city. Dublin City Council acknowledges that there are up to 60 hectares of vacant or derelict land in the city, across hundreds of sites, some large (the Office of Public Works on Church Street), and some very small.

Most of these sites are not designated derelict. Why?

The Act dating from 1992 specifically states that a “derelict site” means any land which “detracts, or is likely to detract, to a material degree from the amenity, character or appearance of land in the neighbourhood” because the land in question may be “neglected, unsightly or objectionable”.

Seems pretty clear to us as to what should and should not be designated a derelict site. The penalty for the owners is a 3 percent annual levy on the value of the land. With 60 hectares of vacant (derelict land?) in the inner city, that’s potentially both a lot of dereliction and a lot of (lost) public revenue.

So why are so many derelict sites not officially designated derelict?

Here are our top 10 reasons, official and unofficial, real or imagined, as to why we think legitimate derelict sites are not officially designated derelict by the local authority. We have heard these reasons (excuses?) too many times.

1. “You confusing the Derelict Sites Acts with the (new) Vacant Land Levy Act.”

Not so. The Derelict Sites Act says very clearly that a site can be designated derelict if the land “detracts, or is likely to detract, to a material degree from the amenity, character or appearance of land in the neighbourhood”. Most of the vacant sites are both vacant and derelict.

2. “The courts do not uphold our derelict site designation.”

Where is the evidence? How many local designations have not been upheld by the courts? Is this list published annually? Is it five, ten, twenty?

3. “It’s complicated. There are very often unresolved title issues that prevent us issuing a derelict site notice on the owner”

Again, where is the evidence? How many? Why not publish this list of unresolved sites?

4. “Much of the land is public owned and therefore the act doesn’t apply.”

Untrue, the act specifically does not exclude public authorities (other than the relevant local authority).

5. “If the site is officially designated we are committed to the compulsory purchasing of the land.”

This is another local red herring or planning received wisdom masquerading for fact. It is simply not true.

6. “Too much ‘derelict’ designation would reflect badly on the city.”

This is a fear of some decision makers that despite the Celtic Tiger boom when the economy grew at an average of 6.7 percent for 15 years (from 1992 to 2007) some 63 hectares of “derelict” land continued to remain undeveloped in the city. This perspective is both unnecessarily defensive and short-sighted. Inner urban vacant land is a resource. It is a FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) opportunity. We should advertise it.

7. “You are unnecessarily penalising development.”

Development is a business. If you fail, go under, tough, get out. Others are queuing up to replace you. Protecting failed developers is misplaced. It potentially prevents capital flowing into the city and it can, and very often does, delay much needed housing construction.

8. “There is a planning permission on the site, development is imminent, no need to designate.”

How many times have we heard that? It doesn’t mean the site is not derelict. Besides many planning permissions can and are extended for years and nothing happens on the site.

9. “It’s onerous for the land owners, counterproductive.”

Onerous unlikely, but a penalty, yes. (See point 7 above.) It’s a tax on unsightly derelict land that should be developed. The act was introduced in part to prevent land hoarding.

10. “The Derelict Sites Act only applies to rundown buildings; it does not apply to empty land.”

Not sure where or how this notion gained traction but it is utterly false.

The city has itself calculated that there are 63 hectares of “derelict” (as understood by the lay person) or vacant land in Dublin’s inner city. Assuming average land values of 10 million per hectare, which are the current land values in inner city after a cycle of boom, bust and recovery, how much revenue has been foregone by the city?

Applying the Derelict Site Act’s 3 percent levy on just half of that land since the year 2000 would generate a grand sum of €75,600,000. Most derelict or vacant land has in fact been derelict or vacant a lot longer than that. So this is a cautious underestimate.

That’s a tidy sum: €75 million that could have been invested in the inner city. How many street trees or children’s playgrounds would that have generated?

There is an eleventh and altogether more convincing unofficial reason: “Vested powerful land-owning interests have successfully opposed designation.”

Redrawing Dublin would suggest there is also an altogether more banal and slightly more dispiriting reason. We simply don’t see them.

When we say “we” we mean the powers that be, decision makers, most of who live in far flung suburbs, few of whom walk daily or even recently in inner city neighbourhoods pock-marked by depressing derelict sites.

“We” (they) literally don’t see them, don’t walk by them, don’t live near them. For most decision makers derelict sites are simply patchwork of colours on a map at a scale of 1 to 1000.

They are neither lived nor experienced. For many others, it’s a case of simply having grown accustomed to them. The sites have become strangely invisible because ironically they have for far too long been visible. They simply blend in to an expected accustomed inner city landscape. They have become an intrinsic part of the city. They shouldn’t be.

These sites are a blight with real social and economic opportunity costs. What are the negative and calculable costs to local business, residential amenity, lost investment, mental health and social justice? Calculating the potential lost revenue, that’s easy, €75 million alarming as that figure is, it is however not the real cost. We have never endeavoured to calculate the real opportunity costs. We should.

How do we score? We’ve come up with our own super-geeky marking system: 40 percent for food, 30 percent for the experience, 20 percent for the “regeneration impact”, a subjective take on the impact of the restaurant on the immediate area, and 10 percent for value for money.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.