What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Redrawing Dublin recently visited Fish Shop on Queen Street to try the brill and have a look at a big problem blocking the area’s regeneration: traffic.

In a new series, the team behind Redrawing Dublin will explore how restaurants can help to regenerate areas, with articles that both review restaurants and the challenges facing their neighbourhoods. There’s more on the idea behind the project here.

For the first review in our Feeding Regeneration series, we have decided to visit a relatively recent arrival to Dublin 7.

Fish Shop opened in 2015 to generally favourable reviews. Twelve months later, it is still going strong – so strong, in fact, that it can be quite hard to find a table in this small fish-and-chip eatery. This week, the restaurant made the Independent’s list of the 100 best places to eat in Ireland.

Fish Shop is an intimate dining experience. The restaurant hosts six tables, with enough room for just two people per table, and has four bar stools facing the street window.

The Friday night we dropped by, we had to wait more than an hour before they called us back to say a space was available. It’s not possible to book a table Fish Shop. Patrons are usually sent across the road to the Dice Bar to wait.

Walk into Fish Shop and you immediately understand what this place is all about. A strong smell of deep frying hangs in the air.

First impressions: cheap and cheerful and plenty of wood.

The décor gives the appearance of a low-budget fit-out. Low-budget or not, the place is tasteful and charmingly done. A large wooden bench runs the length of one wall. The plywood sheeted floor, oiled with red pigment, helps to generate a cabin-on-the-beach ambiance.

A string of single light bulbs runs the length of restaurant. The singular beautiful photograph on the wall of a little wooden cabin on a beach with a neon “Fish” sign sets the tone. You can imagine the sounds and smells of the beach. If you are looking for fish, this is the place for you.

The entrance to the restaurant has a double door, which is helpful given the busy stream of traffic outside. On a cold early spring night, however, and given the intimacy of the place, it wasn’t enough to prevent a whirl of frozen air from blowing in every time it opened or closed.

The menu is small, with four starters and five main courses.

We chose the mussels, cockles, parsley and garlic (€7.50), and fried oysters with apple (€7.50) as our first courses.

With a ratio of about seven mussels to each cockle (if you are unsure about risking cockles), the cockles and mussels tasted fresh, and the chopped parsley gave the main flavour to the dish.

The deep-fried oysters came with a vinaigrette seasoned with freshly cut crunchy apples. The oysters were a delight, the tempura crackling in the mouth before the oozing, salty oyster flesh slipped out in a single bite. Yum.

For our main courses, we went for the two flatfish on the menu: the slip sole with caper butter (€15) and what seems like the flagship dish – wood-roasted brill (€19). For sides, we took steamed greens (€3.50) and chips (€3.50).

The sole was solid, but in a good way. It didn’t have those melted edges that you occasionally find in sole. The flesh remained intact and was both succulent and meaty. The capers were pickled, which gave the sauce a vinegary flavour. It was a simple dish, simply done, and very enjoyable.

Expectations were high for the highest priced dish on the menu. You don’t find brill easily, let alone a wood-roasted one. Brill is usually considered something of a low-cost turbot, but not necessarily a less tasty one. It is generally considered to be somewhat sweeter.

It is a big, round, striking-looking fish – one of the ones with both eyes on same side of its head. The whole fish came face up on its grey-brown dark side.

Cooking an entire fish in its skin by wood roasting runs the risk of creating a slightly sweaty taste. Fortunately, this wasn’t a problem.

The fish was oily and moist. Brill meat flakes are distinctive in size, very flat and wide, which gives the fish an unusual texture.

The side dish of steamed greens – crunchy kale and sweet baby broccoli – had a wonderfully strong garlicky and salty flavour. It was the best dish so far.

The chips appeared to have been hand cut. They may have been boiled before being deep fried, as the potato flesh was very soft. Tasty.

For dessert, we had expected that Fish Shop might have continued with a maritime or beach theme, and taken the plunge with something playful like watermelon or sorbet icepop.

To be fair, watermelon is not in season locally in March. Instead, there were just two dessert options written on the white-tiled wall. The first was almond tart, poached pears, and salted caramel (€6), and the second was lemon posset with short-bread rhubarb.

Neither somehow seemed to fit the image of the place. One tends to associate “almond cake with pears” with afternoon tea in an altogether different ambiance and location. Perhaps the “salted caramel” was a nod to the ocean.

We ordered the almond cake to share. How wrong can you go with almond cake and pears? Not wrong at all here. With a creamy yogurt on the side that beautifully balanced the overall sweet and salty flavours, it was pure and delicious and exceeded our expectations.

All in all, we had a very pleasant evening at Fish Shop. The food was good, the atmosphere was great and the service was wonderful. It’s a fantastic addition to the area.

In fact, it is the best thing to have happened in Queen Street since the Dice Bar opened its doors in 2001. They are now almost operationally symbiotic.

Perhaps just one thing let Fish Shop down: the restaurant’s frying smell wasn’t so savoury. With an open kitchen, we left the place smelling as we if too had been fried, along with our dinner. Is this a resolvable ventilation challenge? Hopefully so.

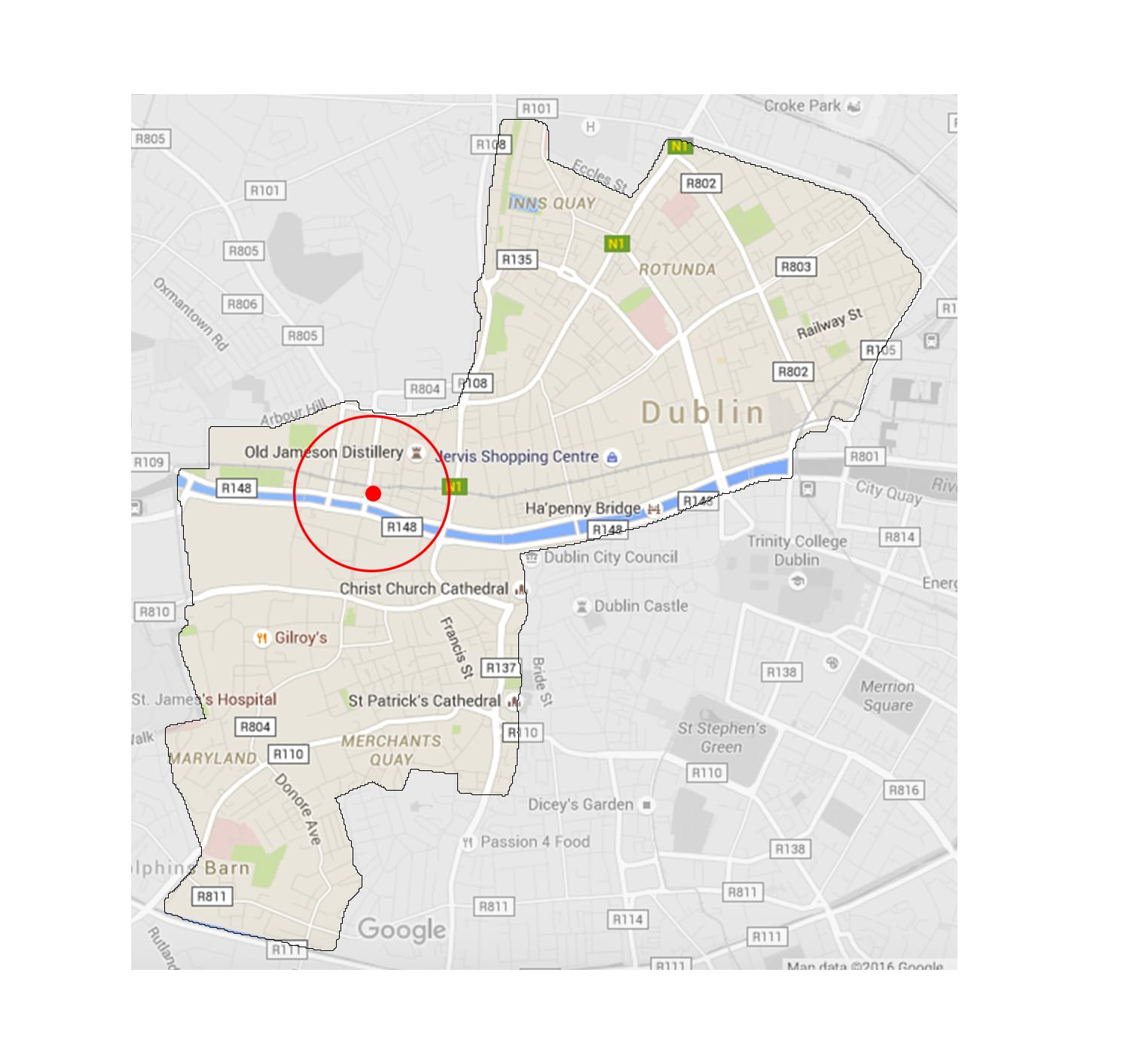

Our local regeneration challenge for Fish Shop is right outside its front door. It’s the traffic. Queen Street is a motorway masquerading as a three-lane one-way regional route, the R804 to be precise.

Restaurant reviewer Catherine Cleary nailed it in an article last May. “It’s difficult to imagine a street less regal than Dublin’s Queen Street. (…) Three lanes of angry traffic are speeding towards the quays, making Queen Street as charming as a motorway siding,” she wrote in the Irish Times.

It’s not just Queen Street. Much of the inner city is dissected, chopped up by heavy traffic, traffic for the most part that is not stopping but going elsewhere, the elsewhere primarily from or to the Dublin commuting suburbs.

Dublin’s inner city and city centre continue to remain in thrall to the private car. Pedestrians remain secondary. Too many inner-urban roads in our inner city, and in this immediate area — think Church Street, Dorset Street, Blackhall Place, North King Street, Queen Street, the city quays — if “efficient” for vehicular movement, are joyless for city-living pedestrians.

They sever emerging and fragile urban communities into isolated, fragmented city blocks of apartments.

Acknowledging this vehicular slicing and dicing of city living is not to stir up another sterile debate about cars versus pedestrians, but to get policy makers and local citizens to rethink the balance between the inner-city-living pedestrian and the suburban-travelling car.

Successful urban living, despite popular perceptions to the contrary, is not hostile to either the ownership or the movement of the private car. It simply tries to ensure an appropriate balance. It’s worth noting that just over half (or 52 percent) of inner-city residents walk or cycle to work or school. Just 11 percent drive or are passengers in a car.

For the city as a whole, 35 percent walk or cycle. This includes a huge number of suburban children going to school, and 34 percent get to work or school in a car.

More than 70 percent of households living in the inner city do not even own a car. For the 30 percent who do, their cars are arguably relatively environmentally friendly. They often remain in storage, used only for recreation, supermarket trips or the occasional journey out of the city to visit family or friends in the suburbs or countryside.

Walk around the network of primarily residential but car-choked streets in the neighbourhood of Fish Shop: Queen Street, North King Street, Blackhall Place, Church Street. Almost all of the road space for cars is dedicated to movement, so for suburban through-traffic. None, or little, is dedicated for parking, which would be for the most part for locals.

The pavements in many places are relatively narrow. There are few if any street trees. It may come as a surprise to suburban Dubliners, but there are approximately 8,000 people living within a 4- to 5-minute walk of Fish Shop. And they (we) want more road space back to walk, to breath in their (our) neighbourhood.

Imagine one lane of traffic removed from Queen Street and instead a single line of trees. One could even mix it up with an occasional parking space. Why not?

“Yeah, right, and the traffic will be backed up to Santry,” I hear the road engineers pounce.

We are not so sure. Outside of peak times, for 20 hours of the 24-hour cycle each day, many of these roads have much more space than is needed to carry traffic.

Our inner-city roads are designed to ensure the maximum free flow of peak – which means suburban – traffic during very short periods of the day.

In plainer language, and it’s simple to observe, these roads are largely devoid of meaningful traffic, practically empty for long periods of the day.

This has real social and economic costs. Pedestrian comfort, street greening, a more beautiful and healthy and liveable inner city is sacrificed.

If we are designing our city to facilitate speedy access from and to it for suburban commuters, we are not only choking the potential to make our inner city more liveable, but, ironically, sustaining the liveability of suburban sprawl. We are also choking the local children living in the area, many of whom are disadvantaged.

The costs to the economy of Dublin, and the cost to the health of its local residents, of a pedestrian-unfriendly inner city are simply not calculated. They should be.

How do we score? We’ve come up with our own super-geeky marking system: 40 percent for food, 30 percent for the experience, 20 percent for the “regeneration impact”, a subjective take on the impact of the restaurant on the immediate area, and 10 percent for value for money.