What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Edmond Sheeran first played for Shamrock Rovers FC in 1938. He was 18 years old.

From Harold’s Cross, father and son would set out for Phibsborough.

As their cross-city trek ended and Dalymount Park approached, Edmond Sheeran, aloft on his father’s shoulders, would ready himself for the game, edging through the crowd, and take up his position as spectator.

Not too many years later, he would move even closer to the game, taking up position as left-winger for Shamrock Rovers, and later, in Dalymount itself, for Bohemians FC.

Now 96, Sheeran is the oldest surviving player for both Bohemians and Shamrock Rovers. As he tells it, his was an age when football was played fair, played clean.

In his terraced house by the Skerries seaside, Sheeran sits alone. He has thinning white hair and wears a crisp, blue linen shirt.

“I’m a bit wonky these days,” he says, as he tinkers with the spectacle cases and handkerchiefs by his side.

He steadies himself for a moment, grabs hold of his stick and moves into another room. “Ah yeah,” he says, as he disappears. “Shamrock Rovers, Dalymount Park, those were the days!”

Sheeran, in those days Eamonn, or “Emmo” as his teammates later nicknamed him, started at Shamrock Rovers FC in 1938. He was 18 years old.

He returns from the adjacent room after a minute or two with a hefty plastic bag, and places it next to him on the couch. He won’t reveal its contents just yet.

Back then, Rovers played on the south side of the city at Glenmalure Park in Milltown. “They [Rovers] were a tougher mob, a rougher lot,” says Sheeran. “But I was there for seven years.”

One of the 1938 Rovers team that retained the League of Ireland trophy, by 1945 he’d readied himself once more for Dalymount Park.

When he talks about his time at Bohemians, the names of his teammates and opposition players come quicker. He recalls an early form of crowd control with a smile.

“There was no rowdiness back then,” he says. “If someone was messing, it was ‘Hey, you! Out!’”

He raises his finger in the air and makes several plucking motions with his thumb and index finger. “You! Out!” he repeats, several times.

His reminiscence suddenly stops and he gazes out the window onto the sea. During our conversation, Sheeran pauses like this every five minutes or so, as if considering his next move.

Around the living room are family photos and glassware and paintings. It’s been nearly 70 years since his time at Bohemians ended, so perhaps it’s not at the forefront of his mind.

“It was Fred Horlacher that done my knee in,” says Sheeran, when he starts to speak again. “Oh, but I got him back!”

Horlacher, Jimmy Dunne, Captain Harry Cannon – all great players, all since passed.

Cannon, who played for Bohemians in the 1920s, later took a turn on the management committee at Dalymount. In those days, says Sheeran, team meetings would be held in the secretary’s office.

The groundsman doubled as the trainer at the time, and the players supplied their own gear. Surely there was some recompense?

“Not at all,” Sheehan says, his tone matter-of-fact. “They didn’t even pay for my medical expenses.”

As the crowds squeezed through the Connaught Street entrance to Dalymount, the players would get ready in the secretary’s office.

Often, politicians Oscar Traynor and Alfie Byrne were seen in the stands.

Beaten Them to It

After his footballing days, Edmond Sheeran moved full-time into the insurance industry, and after he retired, his son Alan followed into the insurance trade.

Still, the Dalymount days were never far from “Emmo’s” mind.

“You’d go see the Irish matches in Dalymount Park,” says Alan. “You’d come home and he’d say ‘Where were you?’ – ‘I was at Dalymount Park’ – ‘Oh, I played there many a time’ – that’s what you’d hear. They’re great memories to have.”

Today, Edmond Sheeran is the last of a generation of League of Ireland footballers, says his son Alan.

“He’s the last surviving member of the 1938 team that retained the title at the time,” says Alan. “There was a presentation there at Shamrock Rovers about three, four years ago with himself and a fellow named Eddie Dunn. Eddie’s passed now so that’s it.”

At his home in Skerries, Sheeran Sr reaches over for the weighted plastic bag by his side and peers inside. I ask if there’s anyone left from his League of Ireland days.

He looks to the window again, briefly, and offers a wry smile. “There’s no one as old as I am,” he declares. “I’ve beaten them all to it!”

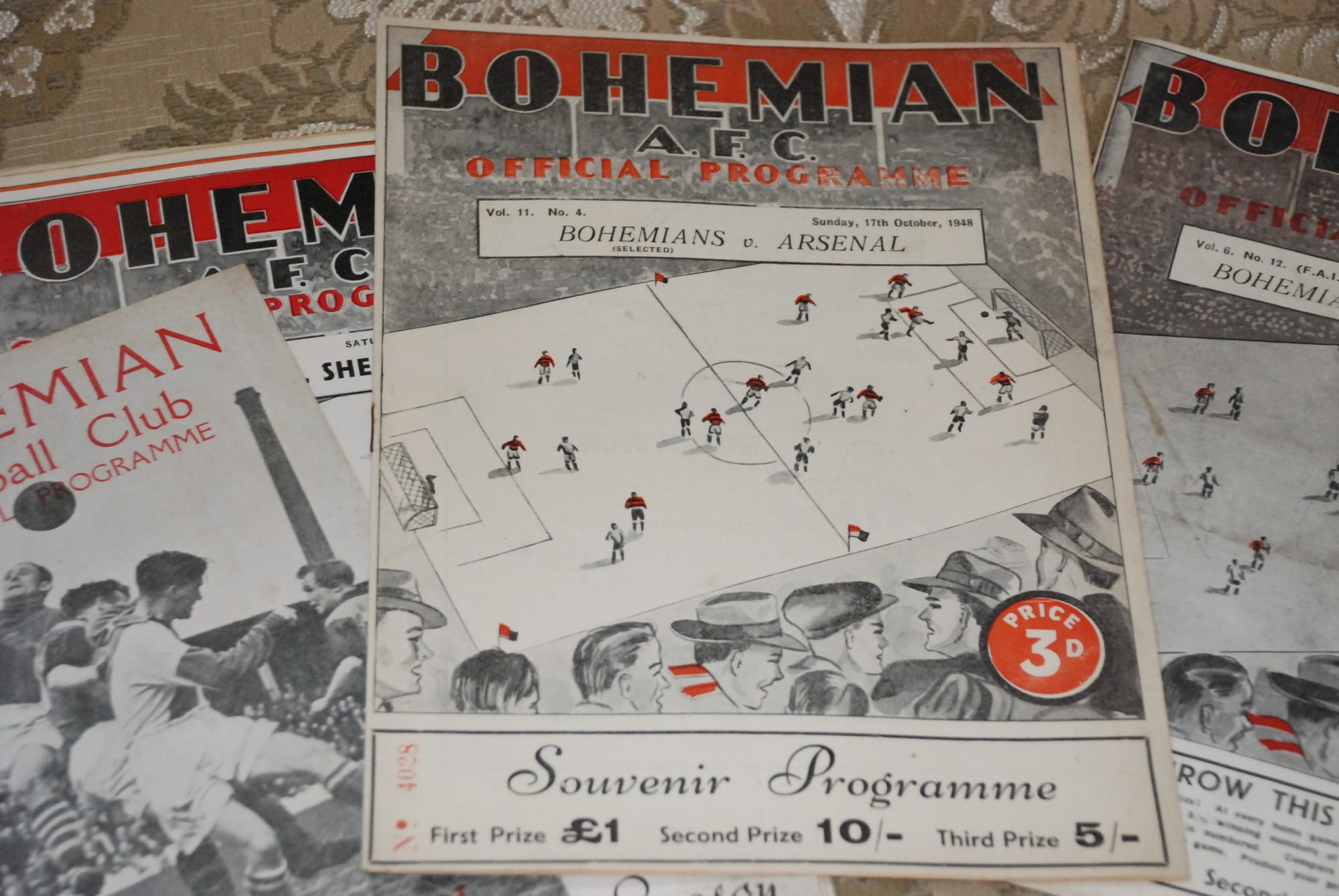

From the bag, he takes out what look like neatly stacked pieces of paper – official football programmes, dating back as far as 1932. They are slightly browned with age but the seams, corners, and covers of each thrupence-a-piece programme remain crisp.

The advertisements inside are from a different footballing era.

“Improve Your Game – Wear Hallidays Football Boots – There’s a drive and a dash added to your play when you use these ‘vitality’ boots!”

“Where Sportsmen Meet – Hely’s – For Guns, Rifles, Ammunition, Fishing Tackle.”

“Everyone To-day tries to BE ECONOMICAL – Value For Money Is The Goal … If You Shop At McBirney’s You’ll Reach That Goal Easier!”

One advertisement announces the release of the new Ray Milland film. Another invites you to a Joe Loss show at the Theatre Royal.

Full-Time

“I’m looking for a buyer for them,” says Sheeran jokingly, as he hands over another programme. “If you know someone who’s interested.”

This particular one is special: on Sunday 17 October 1948, Bohemians FC welcomed English club Arsenal to Ireland for the first time.

The next time Arsenal returned to Dalymount, post-retirement for Sheeran, the Highbury team gifted the fuse boxes for the newly installed floodlights. The same ones still light the pitch today.

Their welcome to Dublin was, the programme notes, “the stuff of which football dreams are made”. But for “Emmo” Sheeran, the beautiful game isn’t the same anymore.

“It got dirtier,” he says. “These days a man would take the legs off another man.”

Goalkeepers are no longer trained like they used to be, he says. Players are paid too much. Managers, the same. Referees are too soft.

“The match should not have yellow cards,” he says, raising his left hand. “Off, Off, Off! You’d clean up the game in six months.”

Sheeran glances out the window once more. He gathers up his programmes, and places them back in the plastic bag. He’d like to return to Dalymount again, he says, but reckons the legs won’t carry him.

In his day, the days of Captain Harry Cannon, and of Arsenal legend Cliff Bastin, he says the stadiums of Shamrock Rovers and Bohemians would be thronged with spectators.

Could it be recreated? “There’s one thing they could do,” says Sheeran. “Let people in for free for six months. That would get your membership up soon enough.”

From the young lad marching over from Harold’s Cross to Phibsborough, to the 13-year footballing career, the rules haven’t changed much. It’s simple, he says. “Play fair, play clean.”