Council official apologises after local residents left out of loop on RCSI’s plans for York Street

Councillor calls for traffic improvements for whole area – not just for RCSI staff and students at the east end of York Street.

It’ll use waste heat from the Poolbeg incinerator, instead of fossil fuels, to warm buildings.

Dublin City Council is readying to apply for planning permission for the next stage of its district heating project, said a council engineer recently.

The idea of the flagship Dublin District Heating System is to take waste heat from industrial sources and use that, instead of fossil fuels, to heat water, and pipe that into the radiators in the area to warm them in winter.

The plan is to start with the waste-to-energy incinerator in Poolbeg, which already generates electricity and feeds that into the grid, and take the waste heat it also produces, and send that into the district heating system.

Plans for the district heating project have simmered along for decades. In 2022, a council official said there’d be homes linked up to it this year, reducing carbon emissions by 80 percent in those areas connected in – but that hasn’t happened.

Efforts have picked up speed, however, since the council appointed a technical advisor for the project, said Karen Kennedy, a senior council engineer, at a climate action committee meeting in late September.

Kennedy listed four phases of the project from here.

The initial phase is to build out the distribution network, the pipes to carry hot water from the incinerator into buildings, to flow into their radiators and keep people warm.

The council plans to apply to itself for planning permission, through what’s known as the Part 8 process, and hire a contractor to build that distribution network and operate it for the council, she said.

The next phase – confusingly called phase one – is to build an energy centre and the rest of the network, which should be designed, built, operated and maintained by a partner, she said.

The energy centre – designed to serve as a backup for when the incinerator goes offline for maintenance – requires planning permission to An Coimisiún Pleanála, said Kennedy, at the committee meeting.

Further along, she said, the idea is to expand the network further west towards the city centre, and south toward the area anchored by St Vincent’s University Hospital – and to connect new heat sources, beyond just the incinerator.

Residents living in the neighbourhoods nearest to the plan, like Ringsend, are frustrated that the network is going to bypass them at first. At the moment, the council’s focus for plugging in buildings seems to be on the much wealthier North Docklands.

“We get the waste and somebody gets the energy,” said Joe Donnelly, who runs the Fair Play Café, a community hub that also serves as the base for the Ringsend Irishtown Sustainability Energy Community.

Dublin City Council hasn’t responded to queries sent on Friday, asking about the rationale for the phasing, and how lower-income households may be taken into account in the roll-out strategy.

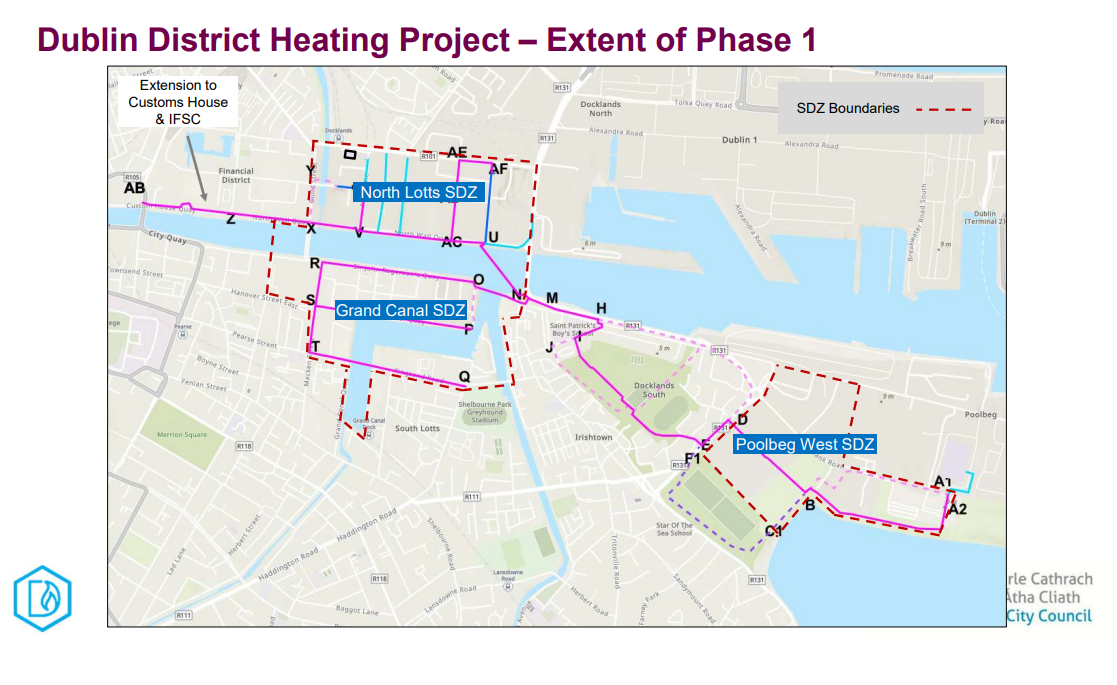

At the September meeting, Kennedy showed maps of the route of the main pipes.

Plans for phase one show heat piped from the waste-to-energy facility, running through Dublin Port lands and the Irish Glass Bottle site, hooking in the 37-acre development led by Ronan Group Real Estate and Lioncor that’s under development there.

From there, it’ll go under Ringsend Park, shows a map for the first phase of the project.

When it reaches the Liffey, one pipe will carry the hot water across the river to the flashy North Docklands, and another would tunnel under the Dodder to the South Docklands, according to the map.

“Our big target area for decarbonising is really the North Docklands,” said Kennedy at the meeting. “So, we’re engaging with a number of stakeholders there, particularly the public sector ones.”

The Central Bank, the Treasury, the Convention Centre – those are the types of buildings the council is really aiming for, she said. “That’s where the big gains are in terms of decarbonising.”

A decade ago, Codema mapped Dublin’s energy demand and found that more than 75 percent of Dublin city areas have heat densities high enough to be feasible for connections to district heating systems.

But the North Docks had the highest energy demand of any area, it said, consuming more than 116 GWh per year in the commercial sector alone.

At the meeting, Fine Gael Councillor Declan Flanagan asked if Kennedy thought that big buildings would apply to connect up.

“We have no commercial agreements yet,” Kennedy said.

They can’t strike those agreements until they have planning secured, through the Part 8 process, she said. “You know, we can’t provide any guarantees.”

But “everybody is very interested”, she said.

Because the plant rooms – the energy hubs – in these big office buildings are choc-a-bloc, so if they are looking to decarbonise, they just don’t have room for the heat pumps they might want to install to do that, she said.

As the council works through its Part 8 process and all the other things it needs to do on the project, the national government is setting up a regulatory framework, she said.

A draft heat bill has been circulated, Kennedy said. As it stands, that would have oblige public-sector buildings to connect to district heating where it is technically and economically feasible, she said.

It would also require industrial facilities with energy input greater than 1MW to connect and supply waste heat to the system.

Clare O’Connor, the programme coordinator for heat with Friends of the Earth, said that district heating roll-outs do need big anchor institutions to make sure they are going to be significantly used.

After that, she thinks existing residents in Ringsend and Irishtown should have the opportunity to connect up, she said.

“From our perspective, it would be important that local communities have access to heating, especially if it is coming from the incinerator,” said O’Connor.

There isn’t that much work that has to be done internally to ready homes to connect to district heating, she said.

“The expense is getting the pipes in the ground and around the city, and getting the pipes to people’s houses,” she says.

Green Party Councillor Claire Byne said that is one reason the council is prioritising the Docklands.

Many of the buildings are already district-heating enabled, she says – and were so even before the incinerator was even built.

Older homes are still part of the plan, she says. “They are, it’s just a more difficult, longer-term higher-budget process.”

“It has the potential for 80,000 homes as far as I’m aware,” said Byrne, of the heat from the system.

Because hooking in older housing in Ringsend and Irishtown – and the city centre later – will require retrofitting the homes, and more underground pipes, the council is trying to coordinate that with Eirgrid’s electrical system upgrades, says Byrne, so that there is less digging up of roads.

Still though, she said, “it’s been the most protracted drawn-out process”.

“We need to get on with this project. We’re decades talking about it,” she said. “We’re decades behind our other cities and counterparts.”

Byrne said residents in Ringsend and Irishtown who were hard-sold the idea of the incinerator on the basis that they would benefit from waste heat are understandably growing disillusioned.

Donnelly, who runs the Fair Play Café on York Road in Ringsend, said that the community nearest to the facility is being bypassed.

“It goes past our front door,” said Donnelly, of the route for pipes. But he doesn’t know if or when he might be able to tap in, he says.

The pipes seem to pass right under the community, he says. “Straight into the poor impoverished residents in Spencer Dock.”

It seems cynical to pass by the small homes along Pidgeon House Road, DEIS schools, and his own community cafe, he said.

There are also social-housing complexes at O’Rahilly House, Whelan House and Canon Mooney Gardens, he said – and not a word of them getting connected.

“It’s a classic situation of how not to do things,” he said. “You should listen to a community.”

It’s inexcusable, he said. “To say you can put up with the smells, the toxins, the traffic – and whatever benefits that would accrue from it would be shipped elsewhere.”

There’s no strategy for listening, for engaging, he said.

Donnelly, who runs the Ringsend Irishtown Sustainability Energy Community, said that they can help with that. “We’re available to help facilitate that and work with other groups as well.”

But it seems as if plans are being rubberstamped at a level that is not accessible to the local community, he said.

At the committee meeting, Kennedy also mentioned energy security as one of the benefits of the project.

Donnelly said that residents living close to the incinerator are discouraged, though. As others, they have faced soaring energy prices that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine and didn’t return to previous levels, he said.

“And this resource is sitting there and nobody from the local area could benefit from it,” he said.

Connolly, of Friends of the Earth, says that there also needs to be a much broader conversation about the district heating models, alongside who is connected up and when.

“There needs to be a guarantee that prices aren’t going to be more than gas or oil, or fossil-fuel alternatives basically,” says O’Connor.

Especially in the early days, when fewer customers are hooked in, she says.

The government’s draft Heat (Networks and Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill 2024 – which sets out regulation for district heating systems – includes provision for price regulation.

Also, district heating should also be set up with an option for community ownership and a cooperative model, said O’Connor.

Projects in Europe have done that, she said. The city of Eeklo in Belgium commissioned a district heating network with a requirement for at least 30 percent community ownership.

“The government now needs to be asking itself about ownership,” said O’Connor.

“I think there’s an opportunity here to do heat and energy differently, fairly,” she says. But the question is whether the government will take it, says O’Connor.

At the climate action meeting in September, Kennedy said that the initial phase of the distribution network, to be delivered through Part 8 planning – which should start soon – would be built and operated on behalf of Dublin City Council directly.

But for the full phase one network, the council intends to engage a joint-venture partner, she said.

The initial phase, “we’re nearly ready to start that”, said Kennedy, at the meeting. That includes segments such as the pipeline to cross the Dodder.

The council has installed some of the distribution network already, she said, down at the Irish Glass Bottle site.

The energy centre is expected to come later, she said. That should sit south of the waste-to-energy facility, and house back-up electric boilers and heat pumps, said Kennedy at the meeting.

That’s needed to keep the system running even if the incinerator is offline. “There will have to be 100 percent back-up because there are outages down at the facility, major maintenance outages every year.”

They will have to apply to An Coimisiún Pleanála for permission for the energy centre, she said.

At the meeting, Flanagan, the Fine Gael TD, asked how long it will take to bring the project to fruition if everything goes smoothly.

Kennedy said that the “target heat-on date” is Q2 2028.

But that would be before the energy centre is built, she said, and it would be “operating directly from the waste-to-energy facility”.

The Glass Bottle Site’s phase two housing is scheduled to be built in Q3 2027, she said. “So as things stand it looks like we may not meet that.”

But then again that programme could be a bit optimistic, she said, so they’re keeping a close eye on the Glass Bottle Site.