What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Cycling advocates say this vastly understates the reality on the roads – and the need for better road designs to avoid such conflicts.

So far this year, Dublin Bus has recorded 68 incidents of conflict between cyclists and its buses, said Andrea Keane, chief financial officer of Dublin Bus, on 3 October.

All kinds of encounters fall within that, said Keane, at the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Justice, during a meeting on enforcement of road traffic offences.

“They could range from an altercation to a cyclist falling off the bike and causing a driver to break harshly,” she said. “So that may not necessarily have been any interaction.”

It’s a tiny number given how many buses crisscross the city. Dublin Bus operates 7,000 trips per day, said Keane.

Peter Collins, a representative of I BIKE Dublin, which campaigns for safer cycling, says that figure doesn’t seem accurate.

There must have been a hell of a lot more than that, he says. “It must be the tip of the iceberg, if there’s that many journeys going on.”

Without a full and clear picture of how often cyclists and buses are scraping by each other on the city’s roads, that won’t be taken into account during road redesigns and driver training, Collins said.

The National Transport Authority (NTA) hasn’t responded to queries sent Friday asking what data for conflicts between bikes and buses they have been sent by bus operators in Dublin.

Go Ahead Ireland, a private operator of 25 routes in the city, also didn’t respond to queries sent Friday asking how many cyclist-driver conflicts it has logged.

Dublin Bus didn’t respond to a query asking how many incidents it has tallied since 2018, or where the 68 incidents Keane referred to happened.

Collins of I BIKE Dublin says that, from his own experience, there are many more close passes, and cases of bottle-necking and tailgating than the number reported to Dublin Bus.

A close pass is when a driver doesn’t leave 1 metre or 1.5 metres of space between them and a cyclist when overtaking. Bottlenecking is when a vehicle pulls in front of a cyclist instead of waiting for the cyclist to pass. Tailgating is when a vehicle noses close to the rear of a bike in front of them.

These conflicts are more minor than a collision, says Collins. But they can still be scary and put people off cycling, he says.

Cyclists can report these incidents to An Garda Síochana through its Traffic Watch department. Dublin Bus complaints go through its customer comment form.

But Collins says cyclists generally don’t bother to take reports to either body, as it isn’t clear if anything will happen if they do.

“If people felt there might be action taken on making a report, or if their report would be responded to, they might be more inclined,” he said.

With both bodies, people have to persist to see any result, he says, and it would be good for people to hear that their report has been logged and there has been an outcome. “Even if they don’t tell you what that outcome is.”

“Somebody cared, somebody took this on board, and hopefully the allegation has been dealt with and that the company is listening,” he says.

Collins says that trying to report and prosecute dangerous driving through An Garda Síochana is frustrating and off-putting, says Collins.

He says he has spent months chasing up many of his reports of dangerous and aggressive driver behaviour to An Garda Síochana, even those with video evidence. “If I didn’t chase them, I’d say they wouldn’t get anywhere.”

An Garda Síochana didn’t respond to queries asking how it responds to complaints that it doesn’t do enough to enforce driver behaviour, and whether laws could be adjusted to make it easier to enforce.

“We monitor the incidence of the cyclist issues very, very carefully,” said Keane, the chief financial officer of Dublin Bus, at the Oireachtas committee.

“All of these issues are recorded regardless of blame or culpability and with the intention of learning and improving from all of these issues,” she said.

Keane outlined responses it takes when cases of conflict are reported. Dublin Bus might make a driver take refresher training, she said.

Their driver training includes classroom and on-bus training about driving around vulnerable road users, she said.

Drivers also learn a cyclist’s point of view through a virtual reality headset, she says. “Which simulates the cycling experience.”

Collins, from I BIKE Dublin, says a bus driver might not grasp the reality of a cyclist’s situation through virtual reality. “I think it’d be more seen as gimmicky.”

Ray Coyne, former CEO of Dublin Bus said in a 2020 tweet, in response to a suggestion that drivers go out on bikes to experience a bus rushing past them in real life, that the activity wouldn’t pass a safety audit.

But it would show drivers what it is really like to cycle in a bus lane, Collins says. “To experience the noise, the sounds, the smell, the feeling of an engine revving behind them.”

“From the windscreen view, when they’re passing somebody, it doesn’t look or feel as close as it might feel on a bike, vulnerable,” he says.

Lots of bus drivers do give cyclists space and hang back, he says. “We don’t often remark on them enough. It does happen.”

But the bad moments stand out when a massive bus flies past. “You’ve no escape past them. It can be very, very intimidating and frightening.”

On 29 July, a coach shaved past Joe Gilligan as he cycled along a quiet Ormond Quay in the evening time, past the pedestrian crossing next to Capel Street.

A few metres ahead, the coach, which had zoomed past him, got stuck behind a row of taxis and buses, shows a video from Gilligan’s bike camera. Gilligan sails back past it.

A close pass like this happens often, says Gilligan. “It’s pure impatience.”

“You get a massive fright because you don’t see it coming,” he says. “Can be terrifying, especially at speed. If you’re not confident you might veer off into the path and injure yourself.”

Collins says that it would be way better if buses and cyclists just didn’t have to share the same lane.

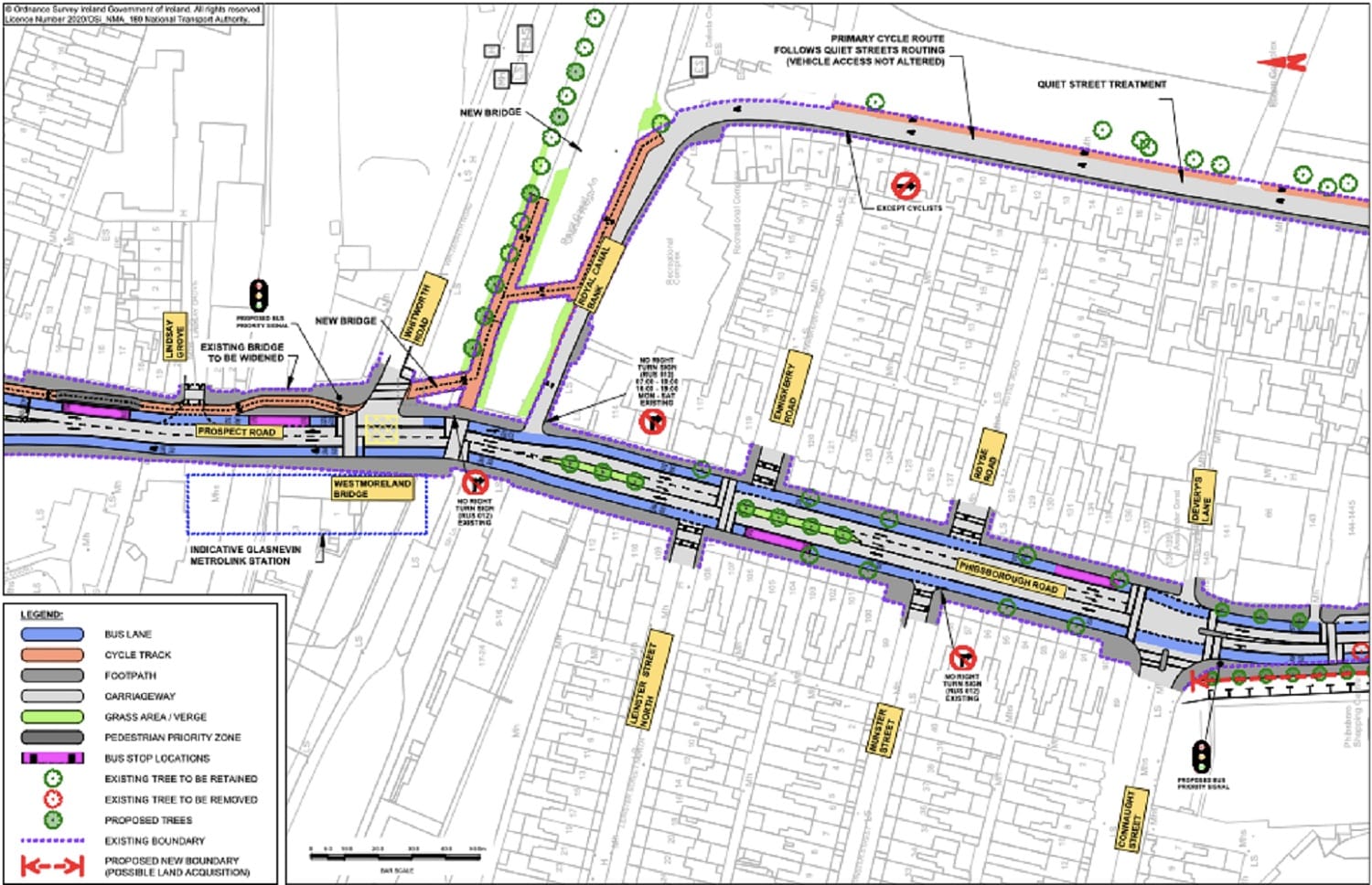

The NTA is designing segregated cycle lanes for cyclists all to themselves on some stretches of its corridors as part of BusConnects, the city’s bus network redesign.

But “BusConnects still leaves large gaps for cycling in Dublin”, says Feljin Jose, a spokesperson for Dublin Commuter Coalition, a group advocating for public transport, walking and cycling in the city.

In Phibsboro, which sits within the Ballymun/Finglas to City Centre Core Bus Corridor Scheme, cyclists will still have to share the bus lane with buses, says Jose.

Proposals also show a cycle lane along Royal Canal Bank, with a greenway past the Blessington Street Basin, rerouting cyclists away from Phibsboro Road.

Jose says this means those rerouted cyclists wouldn’t have to share a lane with buses, but those looking to get around Phibsboro village on a bike will still.

Along the Ballymun/Finglas to City Centre scheme at the moment, 60 percent of the route has segregated cycle routes. After the route is built, 93 percent would have segregated cycle routes.

The NTA didn’t respond to queries sent Friday asking how much of the overall new bus corridors will have segregated cycle lanes, and what the challenges are to having segregated cycleways the entire way along its bus routes.

Designs that make cycling harder and unsafe aren’t good enough, says Jose. “That’s not good enough for now, and it’s definitely not good enough for 2030, by the time BusConnects will be finished.”

The infrastructure network should be designed to remove the conflict points between buses and cyclists, he says. “They have the foresight now to not mix them together.”

Gilligan says BusConnects should include more cycle lanes going behind bus stops rather than in front of the – known as island bus stops – as that would remove a common source of conflicts: buses drivers and cyclists often get in each other’s way as buses are pulling into and out of their stops.

Island bus stops are planned under the Ballymun-Finglas to City Centre scheme, the Clontarf to City Centre Project and the Liffey Cycle Route Project, among others.

Collins, of I BIKE Dublin, says that segregation is important. “Where the conflict can be designed out of it, it’s brilliant.”

“Anywhere where that can’t be the case, it’s back down to driver education and penalties,” he said.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.