What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

A local resident says he has asked for years about the results of testing. DAA says they’re not finalised yet.

Last November, Kenny Jacobs, the CEO of Dublin Airport operator DAA, appeared before the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Transport and Communications to talk about passenger numbers at Dublin Airport.

The final slide of his 43-slide powerpoint mentioned what are known as poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), toxic chemicals found in the soil at Dublin Airport.

Steven Matthews, the Green Party TD for Wicklow, picked up on that. “Does Mr. Jacobs have a rough idea how many tonnes of contaminated soil are to be extracted there?” he asked.

Jacobs said he would need to confirm the exact amount. He also said the PFAS contamination was very low and they were removing the soil anyway. And, he said, “it is not in any water”.

The level of contamination by PFAS in the soil at Dublin Airport, how the airport has dealt with that, and whether the chemicals have made their way into groundwater and surface waters at the airport – and in the wider area – are questions some local residents have been asking for years.

Paddy Fagan, a Santry resident and member of the Santry Forum, a local residents’ group, raised the issue of how the airport was responding to “forever chemicals” as these are known, at a meeting of the Dublin Airport Environmental Working Group in November 2021.

Since then, he has asked repeatedly to see any water monitoring reports but hasn’t been shown anything, said Fagan last week. “They’ve said you’ll get the report when it’s finished. And that’s gone on for two years.”

While Jacobs told TDs that there were no PFAS chemicals in the water at Dublin Airport, a report filed by the EPA with the European Chemicals Agency contradicts that.

“Initial findings suggest contamination of water with PFOS (range 1.25 – 1000 ng/L) and PFOA (2.88-296 ng/L)”, says the 2020 report, in reference to an unnamed airport that the EPA has said is Dublin Airport.

Also, in March 2022, staff from DAA shared two reports it had commissioned with the EPA relating to its site suffering with PFAS contamination.

One of them, dated November 2021, is titled: “Dublin Airport North Runway Development, Groundwater and Surface Water Risk Assessment and Remediations Options Appraisal”, according to an email.

Last Thursday, a spokesperson for DAA said it had hired world experts to help them develop a monitoring programme to understand PFAS levels at their site and how to address them.

“Initial results from campus level monitoring indicate that there is PFAS in both ground and surface water at levels detectable in the laboratory and final results will be shared once the assessment is concluded,” they said.

Results aren’t finalised, they said, “as best practice is to monitor over a period of time to account for seasonal fluctuations”.

Fagan, who used to work at the airport, said he understands that this is a historic issue and he doesn’t have anything against those who work there. “As a matter of fact, thanks to them, I have a house, I have a pension. I have no gripe with them.”

But he can’t understand why they won’t share more details with him about levels of PFAS and how they are dealing with it, he says – even blocking the release of records that he had asked for under the Freedom of Information Act.

“I’m waiting nearly six months now for that to come back,” he says. “Fingal County Council is prepared to release it. The DAA is not.”

PFAS are a huge family of substances, dubbed “forever chemicals” because they hang around in the environment and bodies for so long, building up in concentration.

Studies have linked some PFAS substances to greater risk of cancers, reproductive disorders, hormonal disruption and weakened immune systems.

Because they can repel water and oil, they’ve been used in all kinds of industrial and consumer products since the 1950s – outdoor clothing, paints, non-stick pans.

Monitoring by the EPA has found hot spots for PFAS all over Ireland.

But one major source has been firefighting foams, as is the case at Dublin Airport where they were used in years past, say planning documents. The foams used at Dublin Airport since 2013 don’t have PFAS, so the contamination is a legacy issue.

DAA had found the PFAS contamination in soil as it prepared for some of its expansion works, in this case 12 new aircraft stands in the north of the airport, according to minutes of a meeting between the EPA and DAA.

A spokesperson for DAA said that, “PFAS as an issue is much bigger than just airports alone. It is present in almost every country and landscape around the world.”

He pointed to the “Forever Pollution Project” by a group of European newsrooms, which mapped thousands of contaminated sites across Europe.

“An understanding of the extent of global PFAS pollution is only now becoming clear,” said the spokesperson.

DAA are early movers in dealing with the legacy issues of PFAS, said the DAA spokesperson. “And are happy to work with the relevant authorities to understand the risks and what steps we can take to help play our part.”

Jacob said the soil contamination was at “very low levels”, when speaking at the November joint committee meeting. But if PFAS is found at any level, the soil has to be removed, he said, “and that is what we are doing”.

The minutes of the meeting between the EPA and DAA give a slightly more nuanced description of the levels of soil contamination.

“The quantities of soil generated with PFAS contamination, both trace and elevated, were identified and are significant in volume,” they say, giving a figure of 170,000 tonnes.

The meeting minutes also noted that, “DAA are currently managing and monitoring PFAS in the surface water and groundwater as a separate project.”

Whether or not levels of PFAS in surface and groundwaters at Dublin Airport breach existing and proposed EU thresholds for particular chemicals is hard to glean from the currently published figures.

For surface waters, one type of PFAS – called PFOS – is listed as a so-called “priority substance” under the EU’s Water Framework Directive, meaning it has a legal threshold set out. For inland surface waters, that is an annual average of 0.65 ng/l.

At Dublin Airport, the initial findings for PFOS were 1.25ng/l to 1,000 ng/l – a range topping out well above the EU threshold. But it’s not clear what type of water the test that got that result was done on, and so which threshold (if any) applies.

There aren’t any European Union thresholds for PFAS in groundwater at the moment, says Sara Johansson, senior policy officer for water pollution prevention at the European Environmental Bureau, a network of environmental citizens organisations.

But the European Commission has proposed setting a new legal threshold for a group of 24 PFASs – including PFOS – in both surface water and groundwater. That would be an annual average of 4.4ng/l total, after weighting a little to take the potency of different chemicals into account.

“The European Parliament has endorsed this, but the proposal is being discussed among the environmental ministers,” said Johansson.

Again, depending on the water source tested, Dublin Airport’s initial findings for PFOA and PFOS could put the PFAS levels above these suggested future thresholds.

Last Thursday, Paddy Fagan followed a tarmac path around the eastern edge of Santry Demesne, past open parklands on one side and a forested border on the other.

“We have the lake down here,” says Fagan, as he walked towards the northern corner. “A beautiful lake. The river flows in through that.”

The river is the Santry River. One reason why Fagan and others on the Santry Forum have been trying to get answers about possible knock-on impacts on water at or around the airport is because of council plans for this waterway.

Dublin City Council has been working on the Santry River Restoration and Greenway Project, a plan to bend the river back to its original route, and better manage the growing risk of floods.

Allowing the river to flood its natural courses is great, says Fagan, but he can imagine in the summer, when the river dries up, that people will wander down and picnic at its edge.

And what if the water is contaminated in some way? he asks. “If we don’t know about it, how can we take precautions?”

Residents know that the overall water quality for the Santry River is poor, says Fagan. But they don’t know the details of what is in it.

The river has always been a bit murky, says John Nolan, another local resident on the Santry Forum, standing now on the far side of the lake near the heavily trafficked Swords Road.

“There’s always been concerns about the water quality. It was never particularly pretty to look in at, at certain points as you walk along it,” he says.

“The problem with that is, we’re in a hollow and Dublin Airport is an elevated site,” says Nolan, turning to look northwards, where the airport is some 2km or so away. So, if there’s run-off, some of it is likely going to come towards them, he says.

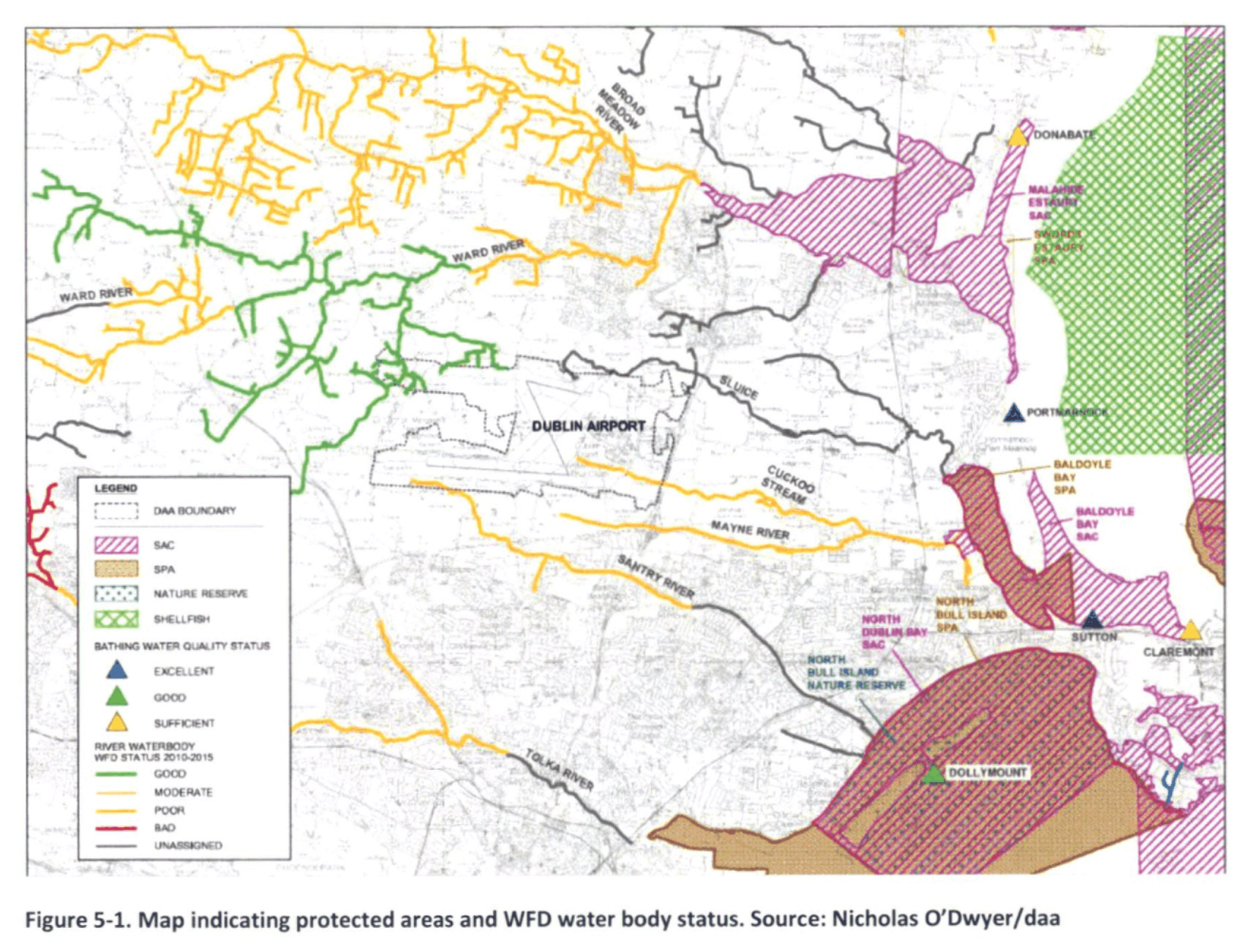

Several rivers and streams flow close to or within lands at Dublin Airport – the Ward River and the Sluice Rivers to the north, and the Mayne River, Cuckoo Stream and the Santry River to the south.

In 2023, the EPA started to test the Ward River and the Sluice River for PFAS, “based on the risk of PFOS and PFOA contamination at Dublin Airport”, said a spokesperson.

Samples from the Ward River last year showed very low levels, under thresholds.

However, samples from the Sluice River last year showed higher rates, with PFOS ranging from 7.8ng/1 to 21.1ng/l and PFOA levels from 10.7 ng/l to 13ng/l – higher than the proposed total EU threshold for surface waters of 4.4ng/l.

“It is likely that the relatively elevated results for PFOS and PFOA in 2023 are due to the proximity of the river site to the potential source of contamination,” the EPA said. “Mitigation measures will need to be implemented to restore the waterbody to good chemical status.”

The EU threshold for PFOS in surface water came into effect in 2018, with the aim of achieving good surface water chemical status in relation to those substances by 2027.

The EPA spokesperson said that sites had been added to its monitoring programme based on a risk assessment of potential sources of PFAS. And, the Santry River hasn’t been added at the moment, they said.

Emails between the EPA and the DAA suggest that the airport authorities have by now been monitoring the water for years.

In one email in March 2022, a DAA official mentions to an EPA scientific officer that there had been rounds of groundwater and surface water monitoring in November 2021 and February 2022, and that it had started monthly monitoring from February 2022.

So, “we should have additional monitoring data available in Q2, late April/early May” 2022, the official tells the EPA, who has asked for it to be sent on.

But Fagan, of the Santry Forum, hasn’t been able to get hard information from DAA about what any of this monitoring has found.

Minutes of the meetings and emails between Fagan and DAA officials show him asking about the tests done on water for forever chemicals – in a letter in March 2022, and at an in-person meeting in March 2023.

In July 2023, Miriam Ryan, the DAA’s company secretary, wrote back to one of Fagan’s letters, saying that the results would be shared once the current monitoring period was satisfactorily complete.

“It is appropriate that we would carry out extensive monitoring over a lengthy period in order to get a full picture of the status of PFAS chemicals on our site, as monitoring may be affected by seasonal weather as well as other conditions,” the letter said. DAA hoped to share results at the end of 2023, the letter said.

In August 2023, Fagan filed a request with Fingal County Council under the Freedom of Information Act for, among other records, those relating to any tests for PFAS in streams and soils on DAA property.

In October 2023, he got a response that Fingal County Council had decided that the records “should be released in the public’s interest”.

But there was still a period for the third-party who the records relate to – DAA – to appeal that decision to the Office of the Information Commissioner. Which it did.

Fagan is still waiting for the outcome of that appeal.

In December, Ryan, DAA’s company secretary, wrote that she now hoped the monitoring results could be shared in the first quarter of this year.

A DAA spokesperson didn’t directly address queries as to whether they still plan to share those results early this year, which period of results it would make public, for which water sources, and covering which PFAS substances exactly.

The EPA has also refused to release the two reports drawn up for Dublin Airport looking into remediation options for the soil and ground and surface waters at its PFAS-impacted site, which were requested under Access to Environmental Regulations.

“The DAA has initiated legal proceedings and the two records are directly related to those proceedings,” said an EPA spokesperson.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.