What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

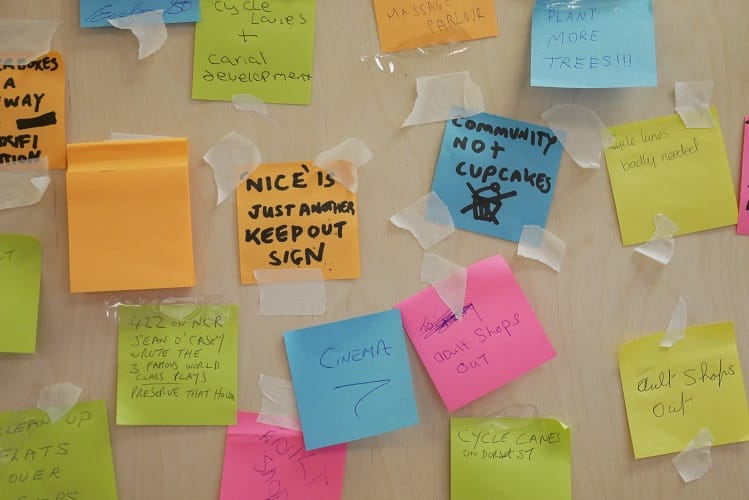

Post-it notes with feedback on a vision for the future of Dorset Street show mixed feelings around the neighbourhood.

Lined with old photographs of the street, sketches and proposed architectural plans, the Dorset Street Together pop-up shop is bright and well-lit.

A handful of people on a recent Friday browsed the illustrations on the wall, taking in what Dorset Street could be turned into.

The shop opened in late October to try to bring people around the street together to imagine what the future might hold, said Ian Ferris.

The idea grew from a meeting between local residents and business owners and Brendan Kenny, the deputy chief executive of Dublin City Council.

“We had a meeting with him about 18 months ago,” says Tony Kelly, of the Lower Dorset Street Community Group, which represents about 200 or 300 people in the area. “We had a number of issues with the brothels and what was going on on the street.”

Kenny said the plan to revamp the street would have to come from the ground up, Kelly says.

But some in the area say it doesn’t feel like that’s exactly what’s happening, that it seems as if new communities haven’t been included so far, and query who the vision is supposed to benefit.

In addition to the Lower Dorset Street Community Group, some members of a local business group Dubh Linn are also involved, says Ferris, its secretary.

The group represents about 80 businesses in the north inner-city, he said. Its directors include businessman Tom McKeon, and hotelier Jonathan Maccumhaill-Binrosli, whose family are involved in several businesses in the area, including the Old Music Shop and the Castle Hotel.

Dorset Street was a retail and cultural hub until the 1960s, but some parts are now “unsightly”, have fallen into “dereliction” and are a “dumping group for everyone”, says Ferris, who is also guest-services manager at the Castle Hotel on Gardiner Row.

“The residential and business community here really had to get together to do something because nobody was else was going to do it,” said Ferris.

Dublin City Council stumped up €20,000 in “direct funding” to support the pop-up, a spokesperson for the council said.

Tacked onto displays around the pop-up shop are images and ideas for what a future Dorset Street might look like.

Dubh Linn and the local residents’ group “tossed around loads of ideas about what it could be and what it couldn’t be – what we could look for and what we couldn’t look for”, said Ferris.

Some of those ideas focus on smarter buildings and better infrastructure. One was that the central reservation along the centre of Dorset Street should be removed, as it “disconnects one side of the street from the other” and more suitable, less “unsightly” planters be installed instead, says Ferris.

The ideas included cycle lanes and wider pavements. “The cars are part of the problem here. The traffic is a big one and that’s not going to be sorted overnight either,” says Tania Miller of Kelliher Miller Architects, who were hired to work with the Lower Dorset Street Community Group and Dubh Linn to draw up the plans.

Another was that the original architecture of the buildings on Dorset Street be highlighted. If you scrape away the facades of the businesses now lining the street, “they will be brought back to the little gems that they were in the 19th century”, says Ferris.

Prettier shop signage was another issue, as was getting rid of massage parlours.

One major part of the plan is the suggestion that Dorset Street could become a “dining destination” and a “place where you have healthy eating, fitness and fine dining”, Ferris says.

One of the panels on display shows pictures of some of the other local businesses on the street, with the header “too many takeaways”.

There are 15 fast-food takeaways, it says, with “closed shutters during the day” and “antisocial behaviour at night”, and which promote “unhealthy eating habits”.

Ferris and Kelly both say there are too many takeaways. They are “unsightly”, “the food is cheap rubbish” and it is “not nourishing at all”, says Ferris.

Not all of those businesses shown in the photos are takeaways, though. Some are affordable sit-down restaurants that, as many establishments do, also offer take-out food.

Miller says the panel wasn’t about a problem with takeaways as such. But about the number and concentration of them. “It’s in excess of a balanced use on the street.”

This means, she says, that many shop fronts are shuttered during the day. “No one’s saying, ‘No takeaways,’” she says.

Lisa Crowne, the co-founder of the arts space A4 Sounds, which is just off Dorset Street, said the throwaway comments about takeaways bothered her. “I find those statements very classist and racist,” she says.

“There was no real thinking about what that means for the families who have been running businesses here for years,” she says. “There was this disregard for their livelihoods.”

It seems to ignore the different communities who eat in many of the restaurants and takeaways, which offer curries or Turkish kebabs, or sushi, or Brazilian food, she says.

Pasha and Wasabi are sit-down restaurants not takeaways, she says. “Maybe your intention wasn’t to be like that, but that’s what you’ve done,” she says. “Then, the class thing of deciding what food we should eat.”

There are fruit and vegetable shops around the neighbourhood, too, but you might not clock them unless you go into some of the minority-run stores, she says.

The idea the takeaways attract anti-social behaviour is unfair, too, she says, and doesn’t really chime with talk as well about the safety of women and the street needing to be busy at night.

She has gotten food and water for free for people who are homeless from some of the takeaways in the past, she says. “They actually provide safety,” she says.

On Dorset Street on Monday, Yusuf Aydin, the manager of Pasha, a Turkish kebab restaurant and takeaway, said he has ideas about how to make the street better.

He pointed to the front of his restaurant, and said somebody had bashed their head through the glass not long ago. There is open drug use, he says.

The street is dirty too, he says, as he walked around the back of the restaurant to the laneway where they keep the big bins. Their black bin, which they chain up, keeps being stolen, he says. “I don’t understand why they stole our bin.”

He would like to see CCTV there and more guards, he says. “The solution is the law, that’s all.”

Aydin said he hadn’t yet been by the Dorset Street Together pop-up shop, or been involved in coming up with ideas for what might improve the street. “Who does takeaways and chippers? Foreigners,” he says. “They produce different cuisine.”

Several other migrant-led businesses on the street said they didn’t know anything about the discussion, either.

Kelly made some comments about some immigrants and the need as he sees it for a hard border around Ireland. But that was nothing to do with the pop-up shop and the future of the street, he said. “Absolutely nothing.”

“We want to see a decent standard of business, it doesn’t matter who owns it,” he says. People are “more than welcome to come in and have a look at it. It doesn’t matter where they’re from”.

Miller, the architect, said they had several meetings since earlier this year and a lot of work has gone into the project.

For her, it seemed rare to see residents and businesses working together. “You’ll often find in areas they have such different concerns, I suppose,” she said.

She said the folks at Dubh Linn and the Dorset community group agreed that for it to work everybody needed to be brought in. “We want people to actually be involved in it.”

There’s a wall of colourful Post-its with feedback from those who have dropped in so far. “Adults shops out”, says one. “No more betting shops!” says another. Others call for cycle lanes, a cinema, or a community hall for Dorset Street residents.

Others, still, seem wary of the overall project. “Community not cupcakes,” says one blue Post-it. “Nice is just another keep-out sign,” says an orange one.

Miller, the architect, says they want everybody to weigh in. “Positive, negative feedback, it’s all actually valuable,” she says.

Some on Dorset Street on a Friday earlier this month said the ideas were a move in the right direction.

“Sex shops and massage parlours are not welcome in the area,” said Denise Hynes, a volunteer at Casa charity shop, stood behind the till.

“This shop has been here 54 years,” says Annette Reilly, a local resident and an employee of Ken Trimmings Ltd, as she helped a customer find the fabric they were looking for. “The hostels and drugs are unreal. It has become a disgrace.”

Some others said they fear that such drastic changes to Dorset Street could dilute the sense of community in the area, and were worried about who has been included in the discussion and who hasn’t.

The street does “need help”, said Robert Devlin, manager at The Bike Institute. But he isn’t sure whether those behind the plans “give a fuck about the small people” or just want to “line their pockets”.

The area “could do with investment”, says Cathy Flynn, a local of Phibsborough and a frequent visitor to Dorset Street. But “it can be done without snobbery and with respect to the current residents and businesses of the area”.

Sinn Féin Councillor Janice Boylan says she would “support the plans once the majority of the people in the community agreed and supported them”.

“The community in Lower Dorset Street is a strong community. They’ve shown that by coming together to actively take part in the process. I think that it is a well-established community that won’t lose its identity.”

At Tuesday’s meeting of councillors in the Central Area at City Hall, both Green Party Councillor Ciarán Cuffe and Fine Gael Councillor Ray McAdam said they wanted to invite those behind Dorset Street Together in to talk about the future of the street.

The project “could be applicable to a couple of other streets in the north inner-city as well”, said McAdam.

Ferris, of Dubh Linn, said there is no exact timeline for the next steps. “We’re aware of how long these things take but we have been promised progress.”

Crowne, of A4 Sounds, says the initiative doesn’t seem bottom-up to her at the moment. She is still wary that it is meant more to please investors than local communities.

“It would be a lot better going around, knocking on everybody’s door and introducing themselves. Inviting everybody along to a public meeting,” she said.

Not everybody is going to attend those, but it’s a start, she said.

– Additional reporting by Lois Kapila

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.