What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

A colourful quilt of 38 patches, each presenting a different work of art, it reads “Welcome to Blanch” in big vibrant letters.

It hangs high over a spiral staircase in Blanchardstown Library.

A colourful quilt of 38 patches, each presenting a different work of art. In the middle, against a red backdrop, it reads “Welcome to Blanch” in big vibrant letters.

One patch features a painting of a Black woman’s oval-shaped face wedged between a tricolour and a Nigerian flag. Above her head, it reads “Ola”.

The quilt’s origin story dates to August 2001. Patricia Newham and a few other local women dreamt it up.

They were dancing with people of the Choctaw Nation at a community centre in Blanchardstown.

The Choctaw people have kept in touch with communities in Ireland since the Famine, when they sent money to help out, wrote Newham later in a booklet.

The visitors were teaching locals to master some dance moves, said Newham, on a recent rainy evening in Clonsilla. “And we were all laughing, we had a great evening,”

After the dance, they talked about all the new faces in the neighbourhood, she says. About how they didn’t know their stories.

At the time, Blanchardstown was just getting more diverse, Newham says. “And I thought maybe it’s about asking people how they came to live in Blanch.”

That thought turned into Crossing Paths, a get-to-know-each-other art project that gave birth to the quilt and inspired unburdening chats between newcomers and Irish people in the neighbourhood.

The idea was meeting people from different cultures, Newham says, but it ended up revealing the importance of getting to know people as people – outside the shadow of those differences.

“The power of actually being listened to and respected,” says Newham, the project’s coordinator, in a video recorded at the time.

Newham and other locals were already involved in Blanchardstown Asylum-seeker and Refugee Network (BARN). Crossing Paths was one of BARN’s initiatives.

The project ran between February and June 2002 for two groups of adults and kids. Government and community organisations like the Department of Justice and the Draiocht Art Centre helped with funding.

Kids from local schools entered artworks to put on the quilt. “Every patch on it is from different groups,” says Newham.

But the quilt is a memento of something bigger. Crossing Paths involved not just painting but photography, poetry, and simply gabbing – sometimes sharing laughs, other times shards of secrets and tucked-away feelings.

All the drawings – even those that didn’t end up on the quilt – were framed and showcased at the Draiocht Art Centre for a month.

“Ultimately, down the road, what we want to make, all of us together, is a patchwork quilt,” Newham can be heard saying in a video taken on the day of the exhibition.

Later, Sr Regina King from Corduff Community Centre – who died in 2015 – helped make the patchwork. “God bless her. She had a women’s crafts group,” said Newham recently.

The wooden rack now holding up the quilt was made by a local woodturner, she said.

Moira Hyland-Doyle, a long-time community worker in Blanchardstown, says the project later inspired free English language classes for adults, too.

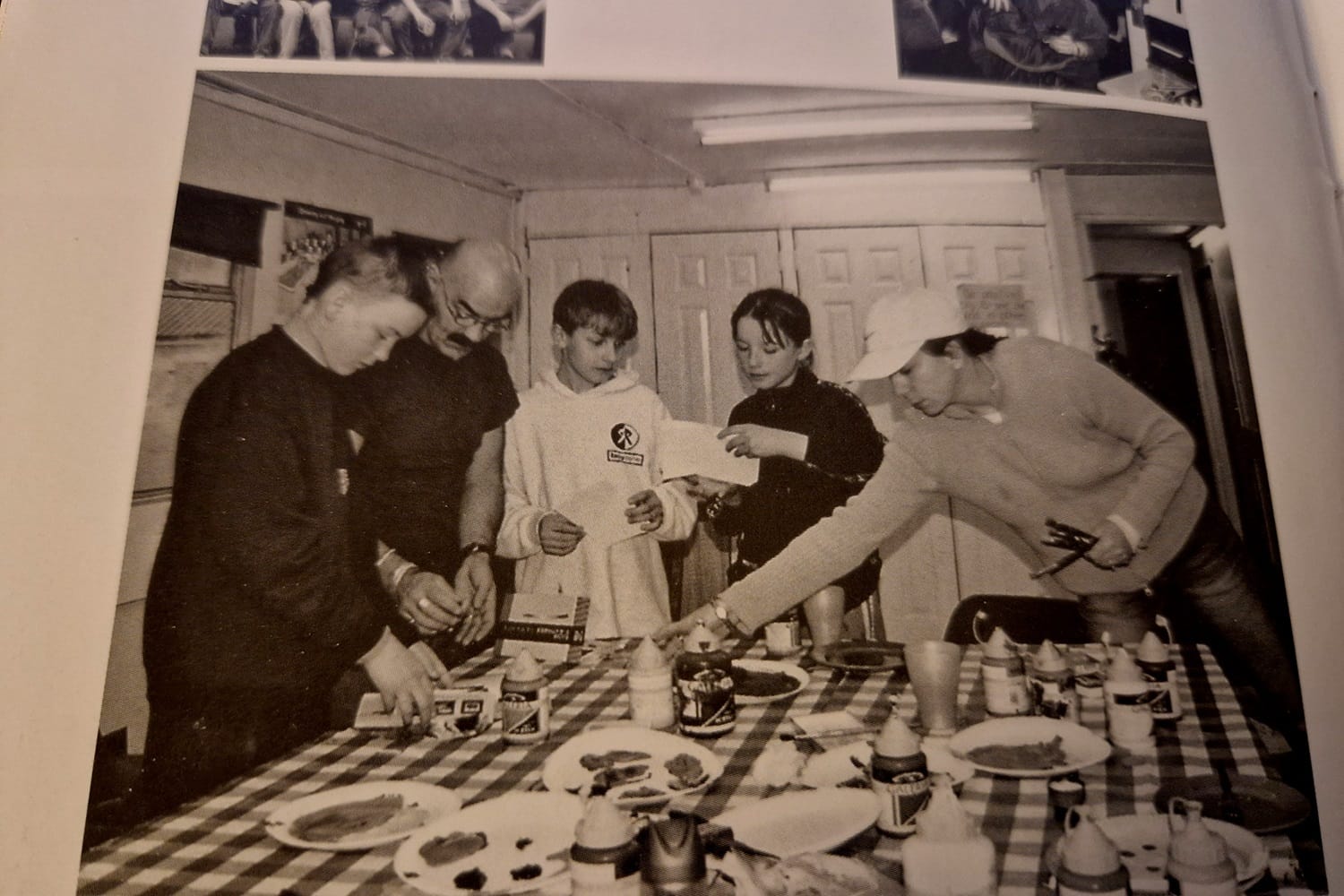

Videos from the project’s workshops show adults and little ones painting, drawing, talking, reciting poetry, singing, sharing food and hanging out.

In one scene, Tony Crosbie, the project’s artistic director, can be heard talking to Lana, a young woman born in Latvia, who insists on living life with a blossomy view.

“The life is blossom, the world is blossom,” she says, paintbrush in her hand and shying away from the camera. “Everybody are blossoms,” she says.

“Good!” says Crosbie, chuckling.

The woman’s artwork, featured in the booklet, shows rain over a grassy field with a giant yellow flower. She’s jotted down “Rain but blossom” on her painting. Half of the words are blurred behind fat drops of rain.

In another scene, three women sing in Russian.

Natalia, one of the women, says how when she first moved to Blanchardstown in September 1998, it felt like a lot of emptiness filled with nothing but a massive shopping centre.

Everyone around her mutters in agreement. “It was not too much people inside,” she says.

Now it’s better. Fuller, she says, smiling.

In another scene, a Black girl from Ivory Coast tells Crosbie that it was tough when she first moved here. “I missed my friends, parents,” she says, gazing down and colouring her sketch.

It’s getting better now as she connects with more people, she said.

A kid complains about losing the fields he and his pals used to play on in Blanch. They’re all construction sites, he says, clutching a juice box. All they’ve got are the roads now.

Crosbie asks if neighbours give them a hard time for playing on the road.

“Get away from my garden, get away from my garden,” says the kid, mimicking a low holler.

His sketch, printed in the project’s booklet, is of a boy’s face full of pimples.

Crosbie, Crossing Paths’ artistic director, is a self-taught artist. Before leaving Ireland for good, he spent a lot of time making art with kids from disadvantaged backgrounds in Fingal.

He also worked in prisons, where he pushed inmates to give voice to difficult, scary feelings with art, says Crosbie.

With Crossing Paths, he says, he was especially struck by how men, regardless of where they were born, opened up to each other. Once during a walk, a guy unravelled and began to cry.

“He was talking about how his wife abuses him when he goes home, physically,” said Crosbie, recently by phone from his home in Barcelona.

Crosbie says it was a big deal—a moment of unburdening that had been hindered for some time by a sense of shame and isolation.

“You seldom hear it from men because of the machoism and, ‘Oh, I can’t say that because that’s not, you know, in the marketplace, so to speak’,” he said.

In another recording from the time, one Irish man – who says he’d just celebrated his 47th birthday with the men in the Crossing Paths group – said hanging out with them made him a better person.

“And I look at people now as they should be looked at, as fellow human beings,” he says.

The tapes show how locals discussed racism and tried to understand each others’ experiences of being othered.

During a group chat, Angela, an Irish woman, said she grew up feeling out of place, too, so she understood.

“I’m not Black or whatever, but I lived the business of being ostracised for something that was completely outside of my control,” she says. “I actually lived it.”

In the booklet, Newham writes of hopes that the conversations between locals and newcomers will stay alive, not just in Dublin and Blanchardstown, but across Ireland.

In August 2023, when locals in East Wall gathered in a meeting where trash was talked about asylum seekers in the neighbourhood, none of the new arrivals were in the room to respond.

Crosbie, the project’s artistic director, says if locals sat down to hear the stories of those new to their neighbourhood today – just like he and others did almost 22 years ago – they’d see just how many worries and hopes they have in common.

“Just say, ‘How’s it going?’ you know, ‘How’s it going?’That just opens up so much,” he said.

Note: Our Brushing Up series tells the stories behind pieces of art on display across Dublin, from paintings in pubs to mossy sculptures. So you can pretend you know your art. You can read more articles in the series here.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.