What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Dublin Cycling Campaign are pushing for a 30 kph speed limit inside the canals. But will that lead to gridlock? (This post includes both an article and a podcast.)

The Dublin Cycling Campaign has formed a new “Action Group” and their goal is to get traffic to slow down. If successful, they think it will improve the lives of all Dubliners, not just cyclists.

“We believe that slower speeds would make streets safer,” says Mairéad Forsythe, who is heading up the campaign’s 30 kph “Action Group.” She and her co-agitators hope they can get Dublin City Council to extend its 30 kph speed limit zone to include everywhere inside the canals.

But won’t 30 kph cause gridlock? Won’t it mean it takes longer for a driver to get across town? We’ll get to that.

Image Courtesy of Design Manual for Urban Roads and Streets (DMURS)

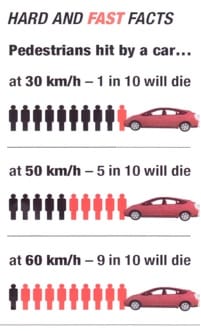

“The first reason for 30 kph,” says Forsythe, “is at 30 kph, 90 percent of pedestrians will survive a collision, whereas at 60 kph, 90 percent will die.” If you’re wondering, that’s also what the Design Manual for Urban Roads and Streets (DMURS) says.

Forsythe pauses, as if a reasonable person shouldn’t require further justification, before continuing. Lowering speeds, she explains, not only make accidents less lethal, but less likely to occur in the first place.

The faster you go, the more ground you cover during your reaction time, and the more distance the car needs to stop. The slower people drive, the less ground they will need to bring their hulking machine to a stop, making collisions easier to avoid.

Forsythe says lower speeds would also reduce noise, making the city “a more pleasant place for people to walk, cycle, play and socialize”.

“More stressed to be honest,” is how Daniel Santos describes how the traffic makes him feel. Santos is a resident of one of the many “two-up, two-downs” along Mount Brown, the road just north of St James’s Hospital, that are separated from the fast-moving traffic by only a sliver of footpath.

“When I come from work, I just keep the windows closed because of the noise,” says Santos. He says he can’t estimate how fast cars go in front of his house, “but it’s really fast. There’s a bit of downhill where they speed up by the hospital – sometimes I’m scared, I’m just hearing the car speeding so fast.”

The street’s speed limit is, like most in Dublin outside the city centre, 50 kph. Eddy, another resident of Mount Brown originally from Ghana, says that cars go a lot faster than 50 kph. He estimates that the average speed of traffic there is somewhere between 60 and 70 kph.

When I ask Eddy if he would let his kids, who had just run up the stairs behind him, go outside to play, he laughs at me as if I had asked if he’d let them play in a snake pit. “No,” he said with a bemused smile, and motioned towards the passing traffic in explanation.

That’s another reason why Dublin Cycling Campaign is pushing for lower speed limits.

“There has been a huge change in how children’s lives are led and we feel that lowering speed limits could contribute to reversing that trend, so that children could come back out onto the streets,” says Forsythe.

At the group’s September meeting, Jackie Bourke, founder of Playtime, an organisation that “works to improve the quality of children’s urban environments”, gave a presentation on children’s right to play in the city.

“Early in the twentieth century, the street was seen, increasingly, as threatening to children,” says Bourke. It was during that time, she explains, that “safer, supervised playgrounds began to spring up to move children off the street.

Bourke references research by Geographer Denis Wood, who argues that getting children off the streets and into playgrounds was done in the guise of concern for their safety, but in reality it was to serve the interests of car drivers – so that they could have exclusive control of city streets.

“Children have a right to play,” says Bourke, who argues that a child should have the “freedom to roam”. Roaming the neighborhood is important for a child’s sense of independence. It helps them grow into well-adjusted adults.

The danger that traffic poses to children, alongside other perceived threats like “stranger danger”, has led us to a situation where parents ferry kids to safe places to play at strictly scheduled times, and the space in between becomes off-limits.

The Dublin Cycling Campaign believes that reducing speeds in the city to 30 kph would make public spaces safer for children to use again. Maybe safe enough for parents to let their kids romp around outside again.

“I think it’s not necessary,” says Giovanni Maieli, another resident on Mount Brown. “Why do you have to go that fast on this part of the street?”

Maieli explains that all the traffic that shoots past his house ends up stopped at the light at the intersection of Old Kilmainham – the continuation of Mount Brown – and South Circular Road.

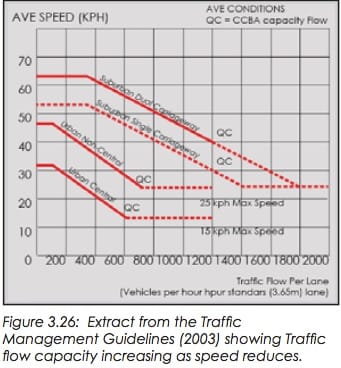

There’s something to that, says Jason Taylor, urban designer and co-author of the Irish Design Manual for Urban Roads and Streets (DMURS). “Generally if you look at getting from A to Z in the city centre, you’d be lucky to average 20 kph,” he says.

Although people go fast when they can, they spend a lot of time stopped at traffic lights. Whether you speed or saunter between traffic signals, your overall journey time won’t be greatly affected.

“In the UK, they’ll drop the speed limit on motorways because it actually increases traffic flow,” says Taylor. It seems counter-intuitive, but Taylor says going slower can increase a street’s traffic capacity, and was recently suggested to ease congestion on the M50.

So reducing speed limits might not significantly affect journey times through Dublin after all.

“There is scope for imposing 30kph speed limits at certain locations in Dublin, however, in our experience a blanket imposition is rarely successful,” says Orla O’Callaghan, a public relations assistant at the Automobile Association, in an email.

“Speed limits need to be in sympathy with the engineering of roads, and should be properly designed,” she says. Strangely, this seems to be a point on which everyone agrees.

“Drivers are primarily influenced by the characteristics of the street environment,” says urban designer Taylor. Drivers go at a speed they think is appropriate for the street, which is why changing the number on the sign won’t have a huge effect on the speed of traffic. A concept that the cycling campaign have copped on to.

“We believe that insofar as possible those speed limits should be self-enforcing,” says the cycling campaign’s Forsythe, citing DMURS.

“A lot of the enforcement should be done by means of changing road layouts. You’d have a narrower road or perception of a narrower road by installing plants and trees,” says Forsythe, which will force drivers to slow down.

Forsythe says the campaign to slow cars down is in its early stages. They are currently reaching out to potential allies like local residents’ associations. The next move will be to put pressure on local politicians to get lowering speed limits on the agenda.

Lowering city-centre speeds, in Taylor’s opinion, “should never be viewed as being anti-car whatsoever, you’re talking about areas where pedestrian activity is particularly high, and a lot of vulnerable users are around – a lot of kids, a lot of elderly, a lot of cyclists. It’s about safety.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.