Did the council follow the correct process to name Herzog Park back in 1995?

Or has Rathgar been living with Orwell Quarry Park all this time?

“It seemed like a good idea at the time,” says Gareth Jones, standing over his own extensive collection, sprawled out over several tables.

“You get to know people quite well. It’s a small scene,” says Clara McGann as her hands rifle through a box of old football match programmes.

“St Patricks Athletic versus Drumcondra – Dalymount Park – St Stephen’s Day 1953,” reads one. “Shamrock Rovers Association F.C. versus Manchester United – European Cup 1957,” reads another.

McGann has just begun her rounds of the hall at St Andrew's Resource Centre on Pearse Street.

It’s Sunday 9 November and The Irish Football Programme Club is having its annual FAI Cup Final Day Fair.

McGann is on a mission.

Near her, at the hall door, an open biscuit tin sits on a table, containing dozens of €1 and €2 coins – the entrance fee.

“A euro, only if you have it,” the man tells anyone who wanders in.

McGann has a lot of boxes and stacks to rifle through over the next few hours. She is hunting for something particular, very particular.

McGann is writing a club history about the Limerick soccer team Breska Rovers AFC, previously known as All Blacks AFC.

She is searching for material relating to a friendly Junior/Amateur International, which involved the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland – played at Century Homes Park in Monaghan on 21 August 2004 – as one of the local Breska Rovers members played in it.

A team sheet or programme would be a huge find, she says.

McGann looks up and around the hall at all the tables she has yet to comb. “I’d better keep going.”

“It’s not a hobby, it’s a disease,” says Anthony Kilfeather, surrounded on all sides by rows and rows of programmes that he’s hoping to offload to fellow enthusiasts.

What he’s selling are just his spares, he says. His personal collection is around 20,000 programmes, and a lot of jerseys, medals and other memorabilia on top of that.

One smiling individual passes Kilfeather on his way to the door, and offers him a hearty “thanks so much again for that”, raising up a bag in his hand.

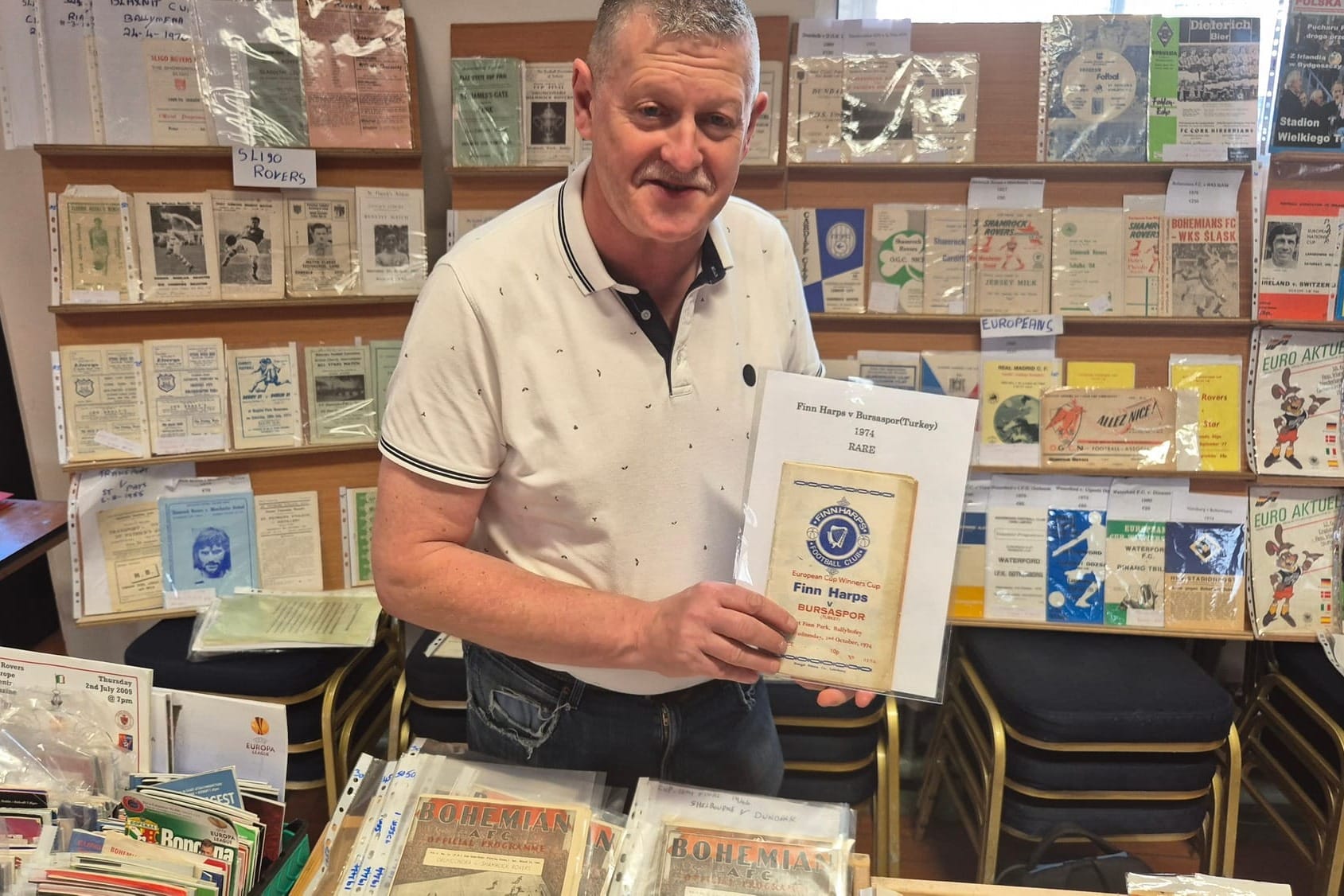

“This one is like hen’s teeth,” Kilfeather says, holding a discoloured white programme with simple blue and red text, wrapped in plastic.

It’s from a European Cup Winner’s Cup meeting of Donegal’s Finn Harps and Bursaspor, a team from Turkey, in Ballybofey, on 2 October 1974.

The programmes were late arriving in the stadium from the printers that day, he says. And when they did arrive, people weren’t interested and so a lot were dumped.

There’s maybe only five or six in existence now, he says. Although, he says he has only ever seen one come up at auction, around 15 years ago.

While the programme was priced at 10p in 1974, today a collector might expect to pay as much as €1,400, depending, he says.

A massive Sligo Rovers fan, Kilfeather will soon be donating much of his collection to a new museum the club is opening to celebrate its centenary year in 2028.

Another Sligo Rovers-related rarity that he’s proud to have in his collection is an unusual medal.

After they beat Drogheda 3-2 in the FAI Cup Final in 2013 and the medals were given out, people realised that Sligo had been misspelled as SILGO.

They had to be returned, and new ones given out.

But one club official slipped Kilfeather a misspelled medal before they were sent back.

“It has never happened before and probably never will again,” he says.

Just then another pair of happy punters pass by and say their farewells to Kilfeather. One bought something from him, on tick.

“You know us. There’ll be no messing,” he says.

“No bother, see you again,” Kilfeather says.

“Cork supporters,” Kilfeather adds, chuckling.

Opposite Kilfeather’s display, Gareth Jones is contemplating his life choices.

“It seemed like a good idea at the time,” he says, standing over his own extensive collection, sprawled out over several tables.

He started collecting 15 years ago, and amassed between 30,000 and 40,000 pieces. But has since sold about half of that, and is on a mission to offload it all.

He says that he has stopped buying and is only selling now.

“I keep the blinkers on. I don’t even look at other stock,” he says.

Moments later, he points to a stack of Norwich City FC programmes from the 1980s and 1990s and admits he’s only just bought them.

He can’t quite explain it.

“Norwich City. Why?” he wonders to himself with a shrug.

Although, Jones says, you never know what strange requests customers will make.

McGann is now much deeper into the hall, still hunting for anything relating to that Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland friendly in 2004.

No sign yet, she says.

But she happily shows off another find. A battered programme from 1951 for the clash of the FAI Amateur XI and Gold Coast at Dalymount Park.

At the far end of the hall, the programmes give way to colourful chorus lines of retro football jerseys.

There are racks labelled “UK”, “World”, “Irish”, and “Kids”.

Each one packed to capacity, as punters leaf through them like pages of an encyclopedia.

A Manchester United home jersey from the 1998–99 season will cost you €200. More recent tops are priced at €60.

Every jersey has a great story, says Barry Rojack, of the Irish Sports Museum, who are running the jersey portion of the fair.

He pulls out a Team GB kit from the 2012 Olympics. It’s unusual because the UK countries ordinarily compete as individual nations at the Olympics, but made an exception when it was held in London.

Then a sleeveless Cameroon jersey that the team wore in the African Cup of Nations, but weren’t allowed to wear in the World Cup.

Rojack points to another favourite of his, a Shelbourne FC jersey, red with blue sides and a large Maximuscle logo in its middle.

It wasn’t the sponsor for the main season, but was used in a smaller tournament, he says.

The club’s former chairman Ollie Byrne, who died in 2007, would organise a different sponsor for non-league matches, to bring in more cash for the club, Rojack fondly remembers. “Just great memories.”

Rojack started the Irish Sports Museum in 2020 with fellow collector Graham Keogh.

The pair also have another company, Irish Sports Collectibles Ltd, through which they sell items. But never online, only in person, Keogh says. “That’s the USP of it.”

What is on display is only the tip of the iceberg, says Keogh. While for this event they just focused on football jerseys, they will often have special displays focused on a particular thing.

Like a collection they had on display of Jordan Grand Prix gear, between the years 1991 and 2003, he says.

Or a display focusing on 150 years of medical doctors playing international rugby for Ireland, he says.

There’s also a sustainability element to what they’re doing, Keogh says.

What they are selling are garments that people still like to wear and would otherwise end up in a landfill, he says. “We rescue what we can.”

What serious collectors are really looking for are the actual players’ jerseys, says Rojack.

He holds up an iconic green Irish football jersey from Italia ’90.

He points at the crest. Embroidered, he says, and not printed like the versions sold to fans.

This particular jersey is numbered 11, which would have been Kevin Sheedy’s, says Rojack.

But it was never worn because it has long sleeves and the weather was too hot for the players to wear them.

How much is it going for now? “Oh, that one’s not for sale,” he says.

People are often surprised at how much he’s willing to pay for old jerseys, he says. “But I look at people shopping in Brown Thomas and think ‘What the hell are you paying that for?’”

There is a funny difference in taste when it comes to match programme collecting, Rojack says.

For people who collect jerseys, they love to see programmes with the player numbers hand written beside their names, he says.

Back in the day, the players’ numbers might not have been printed in the programme, but as they were called out by the stadium announcer, fans would scribble them in themselves.

While this is bad news for programme collectors, for jersey collectors it might be the only way of identifying who wore what, on which day.

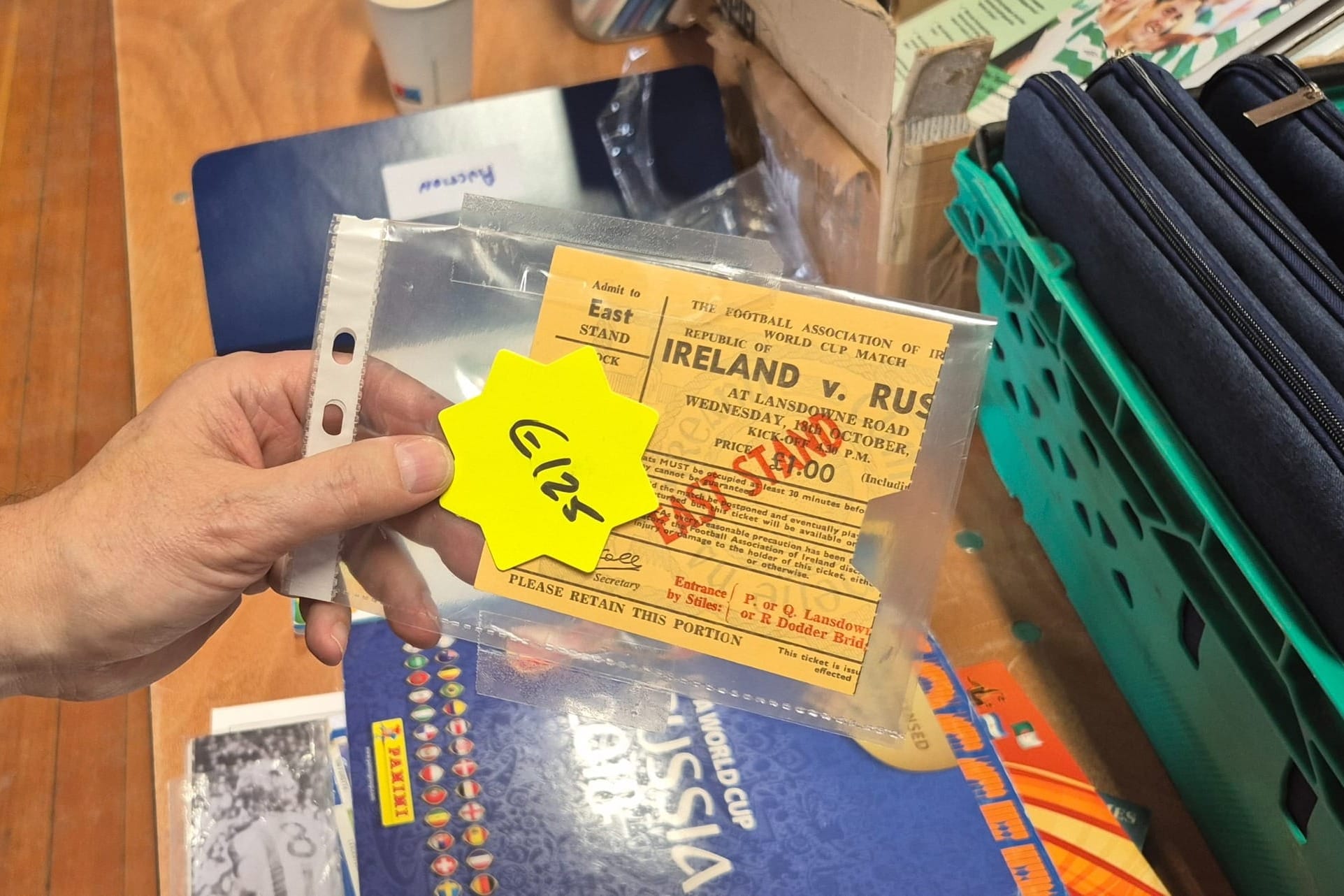

While programmes are the main attraction of the fair, some other items are gaining popularity in collector circles, says Gerry Cunningham, at his own stall.

Because bulky programmes can lead to obvious storage issues, match tickets are all the rage now too, he says.

One ticket in his collection is priced at €125. It was for the Republic of Ireland versus the Soviet Union in 1974.

“When Don Givens scored three goals,” he says.

The ticket is for the old East Stand at Lansdowne Road, so only 5,000 were printed. Now, there’s maybe 200 in circulation, he says.

How do you work out what something costs? Well, he says, when two people want the same thing at the same time, the price becomes apparent fairly quickly.

Cunningham collected as a child, and there has always been a community element to it for him. From the age of 7, he had pen pals around the world that he would exchange memorabilia with.

While the hobby faded as he got older – “you get married” – he couldn’t stay away from it forever, and is now back as passionate as ever. “It’s all about the chase.”

Just then, a man stops and asks for a selfie with him, which he gladly obliges. “He’s over from Scotland.”

At the final table, Clara McGann is nearing the end of her search.

While she hasn’t snagged her prize today, she found a few curiosities to make the day worthwhile.

“Sure, there’s another fair in June. That one’s even bigger.”

For more information on the Irish Football Programme Club, visit their Facebook. The Irish Sports Museum are holding a pop-up shop in Dun Laoghaire Shopping Centre between 8 and 14 December.

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.