What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

A translation of Elias Bouhéreau’s diary tells the story of the first keeper of Marsh’s Library, who fled France, travelled Europe and made Dublin his home.

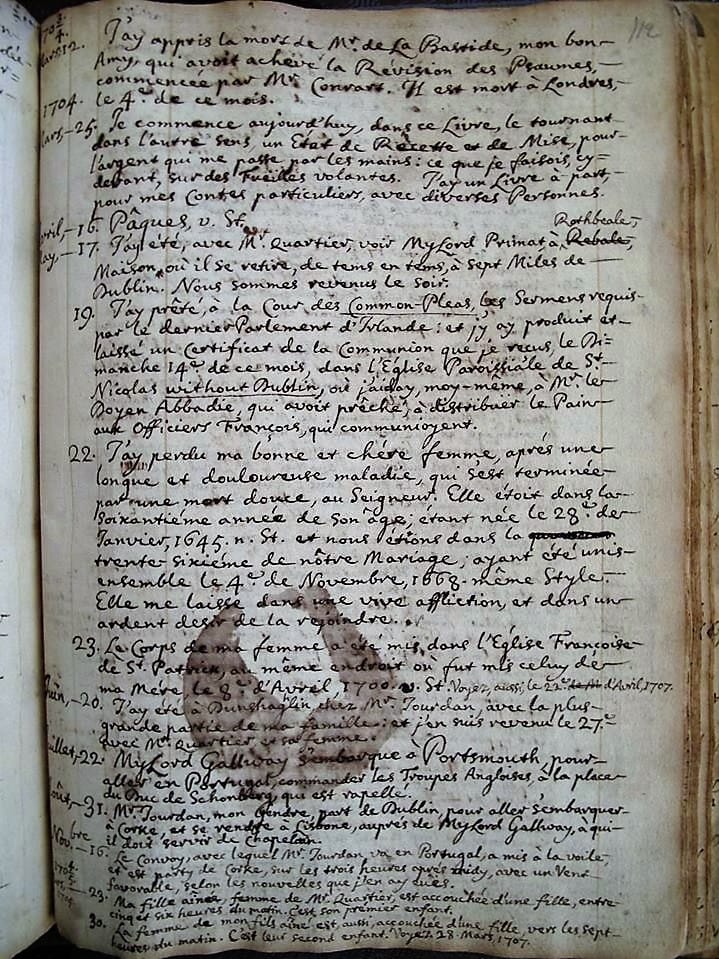

The diary of Elias Bouhéreau is yellowed with age, but the ink is clear and easy to read.

“He has this beautiful hand. That was one of the great things about working on this project,” says Amy Prendergast, who has spent more time recently with the text than many.

“You don’t quite know what to expect from the 1690s,” she said. “It could have been the worst few months of my life.”

Prendergast and another research associate, Marie Léoutre, have spent the last eight months at Marsh’s Library on Patrick’s Close, transcribing and translating Bouhéreau’s book from French.

In it, they say, are stories of travel, clues about seventeenth-century Dublin mores, and also a reminder that today’s refugee crisis is not the first that Europe has seen.

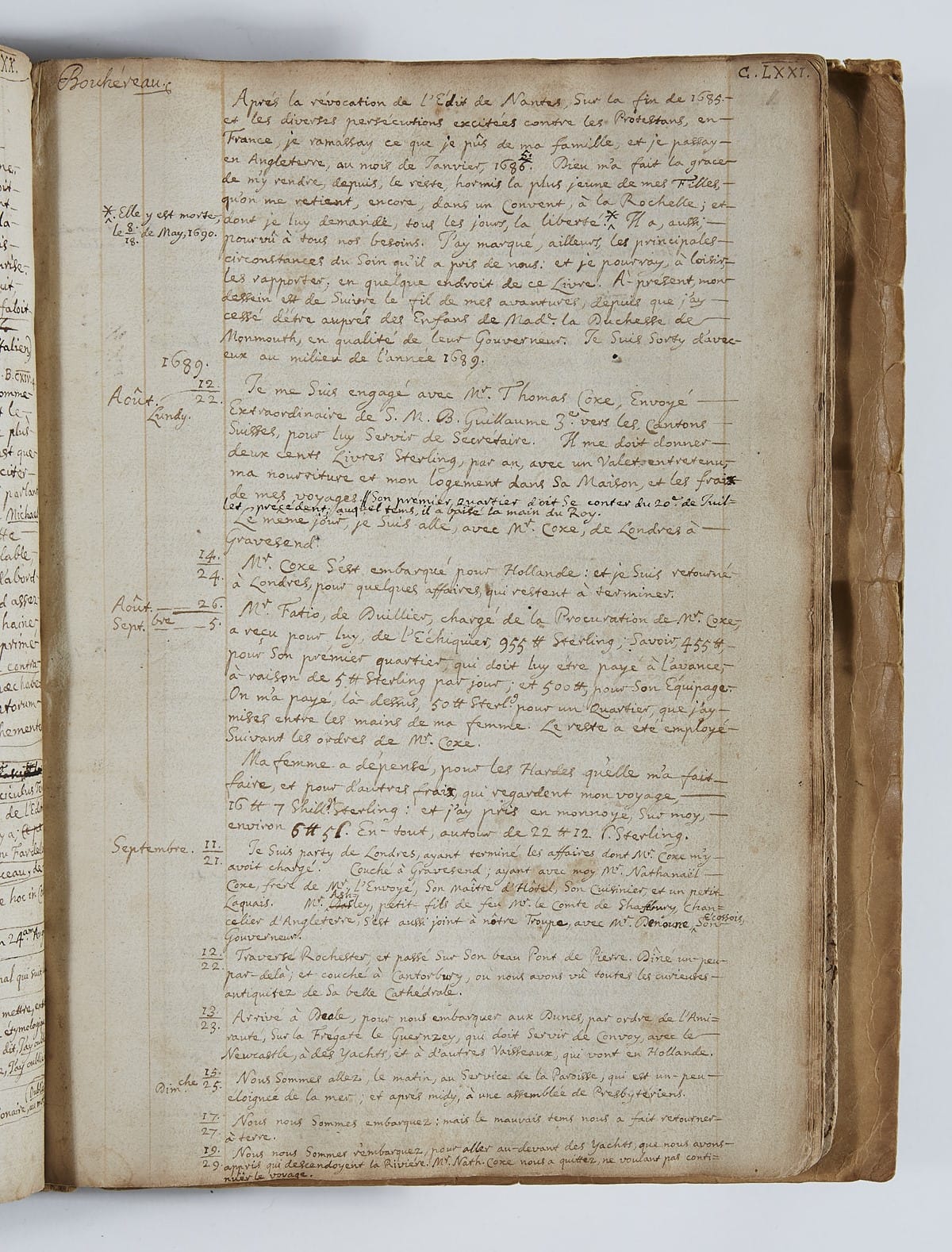

Bouhéreau was the first keeper of Marsh’s Library when it opened in 1701, but the 80,000 words that fill the tan book of his life tell stories that date from earlier and later: from 1689 until shortly before his death in 1719. Thirty years in the one book.

Librarians tend to live quiet lives, but not Bouhéreau.

The diary starts when Bouhéreau is in his 40s, just as he flees from France, says Prendergast.

Bouhéreau was a Huguenot. When King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, ending legal recognition of Protestants in France, it meant Huguenots no longer had the right to practice their religion without persecution from the state.

So thousands fled, including Bouhéreau, who went to England along with his family and his collection of books, which are housed in Marsh’s Library today.

As Prendergast sees it, there are roughly three periods in the diary.

First, Bouhéreau arrives in London, where he becomes a secretary to the envoy of William III, and sets out on diplomatic missions to the Swiss cantons. This features his observations on his travels.

“That bit I absolutely love,” says Prendergast. “You get his whole travel route and all the different towns he stops in. We see what he thinks of the inns, the food, women’s clothes.”

There, he spent time giving passports to French refugees.

The diary features the phonetic spellings of towns with German names, and Prendergast had to use Google Maps to figure out where he was. In one case, Bouhéreau used a word that Prendergast hadn’t come across before to describe the main feature of a town called Kalkar.

She found the town square on Google Maps, and at the centre of it was a linden tree. This was the word she was looking for. She realised that the square had changed very little since Bouhéreau had described it in the 1600s.

When he returned to his family in England, the number of diary entries subsided. “He’s off enjoying family life,” says Prendergast.

In the second section of the diary, Bouhéreau becomes a secretary once again, but this time for a man known as Lord Galway, another Huguenot exile, who was commander-in-chief of English forces in Piedmont, in Italy.

He records his travels once again, but this time the diary features details of Bouhéreau’s military excursions. “So it’s all digging trenches and people being decapitated,” says Prendergast.

Still in the service of Lord Galway, Bouhéreau finally arrived in Ireland in 1697, and his time here makes up the final third of the diary. In early 1701, he became the first keeper of Marsh’s Library, and the entries become much more personal, says Prendergast.

It still doesn’t feature feelings and emotions, like a diary would today, but there’s lots about his grandchildren, births, baptisms, and godparents.

When his wife, Marguerite, died in 1704, it spawned a somewhat emotional entry in the factual diary. The page is marked by the stain of what looks like a wine glass or wine bottle. It is the only page marked with a stain and running ink.

Bouhéreau is perhaps most demonstrative when he writes about travelling, and describes in detail the length and hardship of the journey. He talks about the conditions of inns with some passion, says Prendergast.

“It’s like TripAdvisor in the 1600s,” she laughs.

Though Bouhéreau didn’t share his emotions in his diary, it’s possible to deduct certain things from his writing.

When he’s in Dublin, he keeps hiring new butlers. “So you can ask if he was an easy man to get on with,” says Prendergast.

He records of the births and deaths of his grandchildren and many of them died, giving an insight into infant mortality in Dublin. “Smallpox was a problem at the time,” says Prendergast.

There are insights into the rules of diplomatic sociability, and the cost of clothes, college fees and food in Dublin at the time. One entry shows he spent £1 6s. on cider.

It also often mentions the Huguenot community in Dublin. Those who conformed with the Church of Ireland worshipped in the cathedral, says Prendergast, and those who didn’t worshiped on Peter’s Street where the National Archives are today.

Marsh’s Library has had the diary since 1915, but it wasn’t just the centenary of that acquisition that made them decide to translate and publish it now.

“We thought it was appropriate in 2015 with questions of what the nature of Europe is and what the nature of national identity is and also about asylum and refuge,” says the current keeper, Jason McElligott.

The diary describes, in parts, the plight of refugees and asylum seekers at this time.

McElligott compares the displacement of people across Europe in the 1680s and 1690s with today’s crisis, and says integrating Irish and French people then would have been like integrating the Irish and Syrians today.

There are some broad lessons from the text. “That it’s a perennial human problem, I suppose. That people are persecuted and they flee and that this is something that we dealt with in the past,” says McElligott.

He points out that even 300 years ago, there were those who didn’t welcome the Huguenots, as well as those who were happy to save them from persecution.

The publication of the diary will be academic in style so it won’t feature contemporary politics, but it is interesting to see history repeating itself, he says.

The Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland says about 50,000 Huguenots arrived in England, and estimates that maybe 10,000 moved to Ireland, although this figure is more contested.

“It’s possible to see that the sky didn’t collapse,” says McElligott.

Although it’s never stated outright, Prendergast says Bouhéreau and his family seemed to settle well into life in Ireland.

Bouhéreau was well-educated and already spoke English by the time he arrived in Ireland.

Prendergast notes the transition of his son’s name from Jéan to Jean, and his own name from Élie to Elias. English words start to pop up more often in the French diary, as does the odd bit of Irish, like uisce beatha.

He refers to “us” and “them” when talking about the English and the French. “He doesn’t see himself as French anymore,” says Prendergast.

The integration of his children and grandchildren is noticeable, she says.

His daughter married a man from Dunshaughlin in Meath. One of his grandsons, meanwhile, is sent to brush up on his French at Portarlington in Laois, where there was a large Huguenot community.

When fleeing from France, Bouhéreau managed to get his collection of 2,200 books out through Paris, while his family left through La Rochelle.

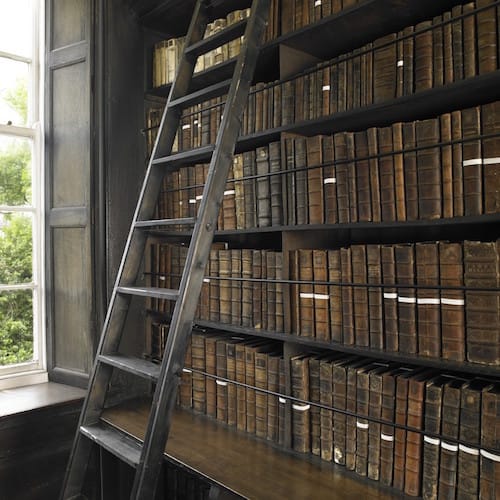

The books made it to England and followed him to Dublin, where the varying shades of brown book spines can still be seen on the shelves of the central reading room in Marsh’s Library.

Many of his books deal with French Huguenot history, and the library still keeps 1,200 of his letters.

Bouhéreau wrote two gigantic volumes on the history of the Huguenots, and the massacres of them, which include some first-hand witness statements.

Perhaps transcribing these will be another project in the future, says McElligott.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.