What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

A short stroll from his Ringsend office, Fine Gael Paddy McCartan talks about the rise of the left in local elections, and how he gave up his car.

I rounded the corner at St Patrick’s Church just as its bells signalled 12pm. Ringsend seems a distinct village, apart from Dublin. The shops on Thorncastle Street resemble any town’s high street, lined with all of life’s necessities: a butcher, a pharmacy, a pub, a barber shop. And McCartan’s Opticians.

Paddy McCartan, Fine Gael councillor for Pembroke-South Dock, grew up in Ballsbridge and has worked as an optician in Ringsend since 1987. He comes out of his office to greet me before we set off for The Bridge Café, across the street.

As we cross, McCartan points to the whiteness of the Wicklow granite that forms the 200-year-old Ringsend Bridge. It used to be covered in black soot, he says. It took him more than six months of hassling Dublin City Council before they cleaned it up.

When we get inside, the waitress tells McCartan that they’re out of scones, apparently knowing what he would order. The Bridge Café is not hip, but seems reliable. The perfect place for a fry-up.

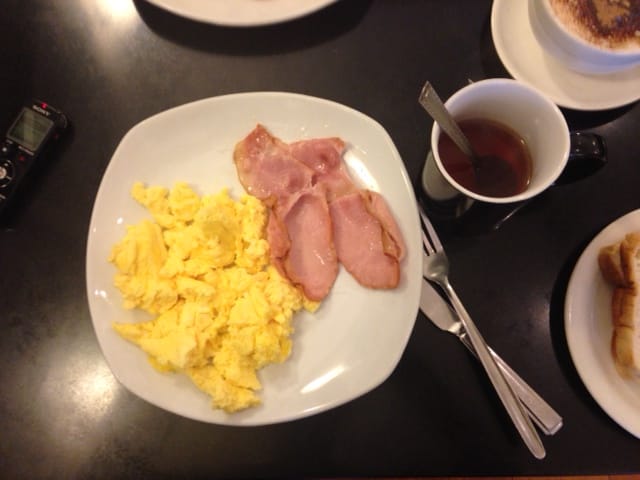

After a reminder that this meal is on Dublin Inquirer, McCartan decides on the bacon and eggs, one of the menu’s cheaper items, and a cappuccino. I choose the same, but with a tea.

Any rapport created in previous minutes disappears when the voice recorder is pulled out. Our words come slower and are more carefully weighed.

We start at the beginning. McCartan joined Fine Gael back when Garret Fitzgerald was Taoiseach in the 1980s. “It was a difficult time for the country, economically,” he says, and one of the main reasons for that difficult time, in his opinion, was the “economic profligacy of Fianna Fail and the malign affect Charles Haughey had”.

To an American, Irish politics can be baffling. There are two centrist-ish parties whose policies are hard to disentangle, but both parties would rather reach to the left to form a government than work together.

McCartan does mention the split during the civil war, but what really seems to differentiate the two parties, in his eyes, is the way they have conducted themselves over the years. “I would like to think that Fine Gael has always put the country first. I can’t say the same thing, from my perception, of Fianna Fail.”

The councillor says he has always been totally opposed to the thought of forming a coalition with Fianna Fail, and it seems he’s unlikely ever to change his mind.

McCartan believes Fine Gael is in a good position at the moment. “I would be very optimistic that, given what has happened in Greece, that the people will realise the steps that were taken by the government were the right ones to secure our long-term future.” But he warns that, “We still have an enormous debt,” which will be lessened, in his view, if we follow the agenda set by Fine Gael and Labour.

Most of the councillor’s criticisms seem to be reserved for Fianna Fail, but the thought of Sinn Fein in control of government, in league with other left-wing parties doesn’t sit well with him either. “There’s no point, in my opinion, of threatening to burn bondholders and saying that we’re going to, in effect, give the two fingers to Europe.”

While the thought of a left-wing coalition government scares McCartan, he doesn’t think the Irish people will vote that way in the coming election. “The Irish have a tendency to indulge themselves in local elections,” he says, and are more likely to vote for independents and fringe parties at that level.

When it comes to the general election and forming a government, he believes people will be more prudent. “I’m not being complacent about it,” he adds.

Fine Gael has been described to me as Ireland’s right-of-centre party. For this reason, I expected McCartan’s views on transport in Dublin to be more old-fashioned.

Not so. The councillor gave up driving 12 years ago, and now walks or takes public transport anywhere he needs to go. He says that, while he has no bias against car drivers, as a walker, he sees the effect “the motor car has on the city, and it’s a very negative affect.”

We spoke about the progressive new transport study released by Dublin City Council. McCartan points out that when the College Green Bus Gate went into effect, people were really against it, but now it is generally accepted to have had a positive affect. The changes outlined in the new transport study will, if adopted, provoke a similar response, he thinks.

McCartan hopes the public consultation will reach as many people as possible. He urges everyone vote. The thought of voting seems to kindle a fire in him. He launches into the subject: “One of my issues with elections is the number of people who don’t vote.”

In the last local and European elections, less than 50 percent of the Pembroke-South Dock constituency voted, he says. “Even in our last election, where our very future was at stake, the turnout was less than 70 percent, which still means that 30 percent of people, for whatever reason, didn’t vote.”

There are ways to engage more people: the voting period could be extended or there could be “more-imaginative use of postal voting” to reach those abroad. He wouldn’t, though, endorse compulsory voting. It “wouldn’t suit the Irish people”, he says.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.