What would become of the Civic Offices on Wood Quay if the council relocates?

After The Currency reported the idea of the council moving its HQ, councillors were talking about and thinking through the pros and cons and implications.

In response, a spokesperson for the council said that “An area’s affluence in no way bears influence on the strategic routing.”

The signs of an ambitious effort to build out Dublin city’s network of cycle routes are everywhere.

There are dashed white lines, rusty-red cycle tracks, bollards and bollards and bollards – and the massive construction project stretching from the city centre up to Clontarf.

At the moment, progress can look a bit uneven.

Cycle west from Clontarf – where this flagship cycleway project is being built – along the roomy segregated cycle track along leafy Griffith Avenue, and all this ends in Finglas. There, the cycle tracks, where they exist, aren’t up to these standards.

Will this disparity remain, though, when the network is complete? Zoom out, and imagine the planned network as a kind of spider’s web, spun by a spider with a pretty avante-garde sensibility.

Get out a ruler and measure the number of kilometres of cycle lanes planned for wealthier areas and for less well-off areas – and the calculations will show that a bit more are planned for wealthier areas.

Now, census figures show that the wealthier areas are bigger geographically, and more people live in them. But even accounting for this, they’re due to get a bit more than their share of the planned cycle network, an analysis shows.

A spokesperson for Dublin City Council says the network was planned based on data showing the routes that people want to travel, and the physical restrictions presented by streets and other factors.

“An area’s affluence in no way bears influence on the strategic routing,” a spokesperson for the council says.

But whatever the reason for this disparity, it’s unfair, says Patrick Dempsey, a Labour Party representative for the Ballyfermot-Drimnagh area.

“Places need investment even if they’re more affluent, they deserve good cycling infrastructure – but so does all of the city,” says Dempsey.

Measuring

On its website, Dublin City Council has an interactive map of its planned “active travel network”, including cycle lanes.

There’s a menu, too, that’ll add a second layer, showing the active travel network – cycle lanes and footpaths – included in the BusConnects redesign of the city’s bus network.

Together, these form the avant-garde spider’s web, the city’s planned network of cycle lanes. It’s already under construction, and due to be built out in the coming years.

To decide whether the area that each segment of this cycle network passes through is very disadvantaged or very affluent or somewhere in between, the Pobal HP Deprivation Index was the measurement.

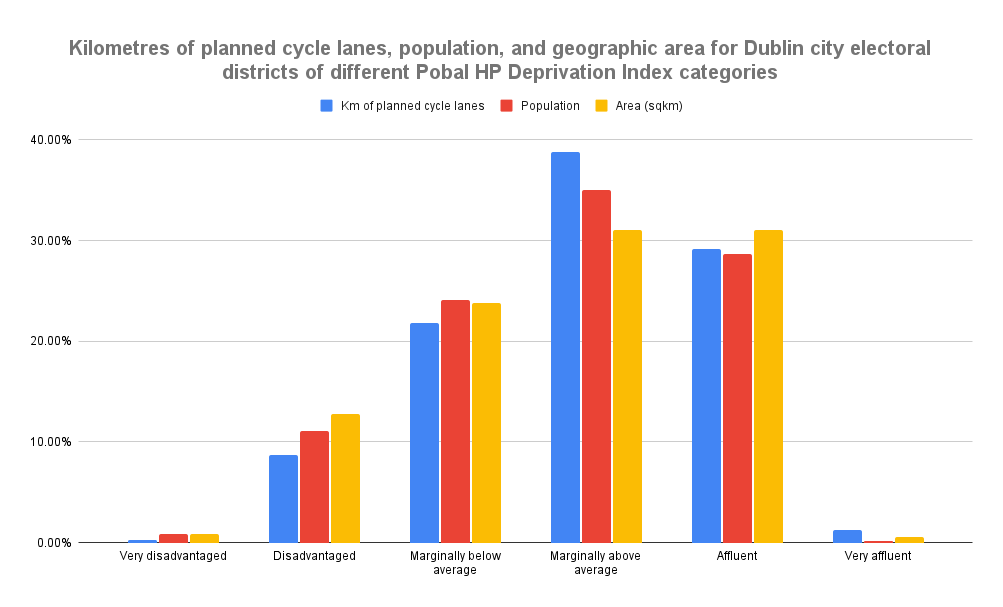

Colouring each of the Dublin City Council area’s electoral districts based on which of the index’s six categories it falls into, and measuring the number of kilometres of planned cycle route pass through districts that fall into each of those, shows a disparity.

Stretches of cycle lane that ran along the border of two electoral districts that fit into different deprivation-index categories were counted twice, once in each category.

In the end, there were more kilometres of cycle route planned for districts that rank as “marginally above average”, “affluent” and “very affluent” than there are for districts that rank as “marginally below average”, “disadvantaged” and “very disadvantaged”.

This disparity persists even when geographic size and population are taken into account.

Electoral districts that rank on the index as “marginally below average”, “disadvantaged” and “very disadvantaged” are each due to get a bit less than their share of cycle routes, based on how much of the city’s geographic area they cover, and population they host.

Districts that rank as “marginally above average” and “very affluent” are each due to get a bit more than their shares.

Green Party Councillor Michael Pidgeon said the planned network is an improvement on the previous more ad-hoc system of putting cycle lanes into the city.

“I definitely noticed that there were definitely, you know, richer parts of the city basically getting them first,” Pidgeon said.

“A lot of the richer areas would probably just see more organized groups, groups that are more effective in getting their point across or have media access, legal access, connections to councillors,” he said.

Also, “I find a lot of the time, bureaucratic systems, again, not necessarily consciously, are designed in a way that middle-class people and office workers understand. So, often, those communities are much better at leveraging and using those systems.”

There could also have been an issue of people in city government giving more attention to parts of the city around them, or the areas they passed through on their commutes, Pidgeon said.

“There’s sometimes just issues that I noticed that some people designing these things, not necessarily engineers, but like you might just get, you know … like, I’ve moved house myself and you’ll naturally find your attention is drawn to the issues and the areas around you,” he said.

“So that can be an issue that if you have a lot of city management that either doesn’t live in the city or the routes that would come into the city would be through these wealthier areas, you know along the coast or something like that, there’d be an aspect of that,” he said.

So, having a planned active travel network is better, Pidgeon said. “I think with the Active Travel Network, it’s substantially more fair minded,” he said. “Because it’s not like, ‘Where are we going to build a lane now lads?’”

A council spokesperson said that, when it’s all built out, it “will bring over 95% of people within 400 meters of the network”.

There will be areas where the network is denser, and areas where it is sparser, and the end result looks set to privilege more privileged areas by a bit.

But you don’t plan a network of cycle routes only to make sure all areas get their fair share of cycle lanes, said the spokesperson for the council, a spokesperson for the National Transport Authority (NTA), cycling advocates and some councillors.

Cycle lanes should take people where they want to go, they said. And, given the widths and layouts of different streets in the city, it can be a lot easier to put cycle lanes along some routes than others, they said.

“The NTA is of the view that all parts of Dublin City should benefit from safe and convenient access to services and employment by cycling, regardless of the socio-economic status of residents,” the NTA spokesperson said.

“Cycling investment, however, is not only targeted spatially on the basis of resident population – to which the deprivation index solely relates – but also towards the significant commercial, cultural and leisure attractors across the City, and on facilitating safe cycling to schools”, he said.

Indeed, the “most important criteria would be, like, where the demand is, where people are likely to use it”, says Colm Ryder, the Dublin Cycling Campaign’s representative on the council’s transport committee. “So the main artery routes would be a prime example.”

Another criterion might be whether there are people in an area who would use a cycle lane if it were built, says Mairéad Forsythe, former chair of the Dublin Cycling Campaign. People in better-off areas tend to cycle more, she says.

“A lot of the poorer areas are outside the M50, so it’s a longer cycle and it’s not really feasible to cycle from somewhere like Tallaght to town every day unless you’re very athletic,” she says.

“Whereas if you live in a more middle-class area, like Terenure, or even Crumlin, which is now middle-class, it’s easier to cycle in and out of the city,” she said.

“The other thing is that people in lower social classes tend to live in terrace houses and terrace houses carrying bikes through is awkward,” she said. “And leaving bikes out the front is not always a great idea in any area.”

Census data on social class shows that professionals and managers are over-represented among cyclists – but so are semi-skilled and unskilled workers.

“Professional workers” were about 9 percent of the population in Ireland, but about 16 percent of cyclists, and “managerial and technical” were 31 percent of the population and 34 percent of cyclists, according to data for 2016.

Meanwhile, “semi-skilled” workers such as roofers, brewers and postal workers were 13 percent of the population but 15 percent of cyclists, and “unskilled” workers such as labourers, car park attendants and cleaners were about 3.5 percent of the population but about 4.5 percent of cyclists.

The group that was most under-represented among cyclists were “skilled manual” workers such as bricklayers, plasterers, plumbers and taxi drivers, who were about 15 percent of the population but only about 11 percent of cyclists.

Aside from putting cycle routes where there’s demand, there’s also the issue of putting them where they can – practically – be put.

Active travel routes are based on “a number of factors including origin-destination data” – where people want to go – “and physical restrictions to name a few”, a Dublin City Council spokesperson said.

There’s plenty of space on some wide streets to add in a cycle lane without too much disruption. While on others, it’d require closing a lane of vehicle traffic, or buying additional land to widen the roadway, for example.

“Looking at the areas that don’t, that aren’t getting cycle provision in the Active Travel Network, even just looking at the map, a lot of the areas that aren’t getting as much are ones where it’s genuinely just physically very difficult to see what you could do,” said Pidgeon, the Green Party councillor.

“I think a big part of that is ultimately that you have these estates that don’t necessarily have roads which would be conducive to segregated cycle lanes because they’re through residential areas where there’s a lot, a huge number of driveways and parking spaces,” he said.

“You’ll see there’s a big hole in the map, basically, around Crumlin and Drimnagh,” he says, by way of example.

Another area that looks a bit left-out on the map is Ballyfermot.

A lot of the parts of Dublin that are getting – and are due to get more – active travel infrastructure “already are within walking distance of the city, so they can walk in”, says Dempsey, the Labour representative in Ballyfermot-Drimnagh.

“They already have a Luas, so they have tram infrastructure. They have frequent multiple buses,” he says. “Ballyfermot, people have a bus – the G1, G2 and 60 – and very poor cycle infrastructure.”

People in more affluent areas have better access to cars, too, says Dempsey. “People in Ballyfermot are far more reliant on public transport and public infrastructure because of levels of deprivation and unemployment.”

Unemployment is high in Ballyfermot-Drimnagh, so the government should be working to make it easy for people to get into town for work, he says. And, of course, also to enjoy the leisure and recreation options the city centre has to offer, he says.

“Good infrastructure is a matter of equity and equality,” Dempsey says. “And really what we’re trying to do is ensure development in public infrastructure is balanced across the whole city.”

The roll-out of active-travel infrastructure has definitely, so far at least, not been balanced across the city, says independent Councillor Vincent Jackson, who represents Ballyfermot-Drimnagh.

“The more affluent areas seem to get the lion’s share of the resources that are available,” said Jackson.

“I know there about a year ago with some of the money that came down from central government, jaysus we hardly got to look in in the South Central Area of the city [which includes Ballyfermot] from what was available to the South East,” he said.

In 2022, Labour Councillor Darragh Moriarty did an analysis of how much money in grants for that year from the NTA each of the council’s administrative areas was getting.

The South East Area has gotten €7,825,000 for projects within its boundaries, while the South Central Area has received €550,000, according to Moriarty’s analysis.

“Where there’s already been heavy levels of investment in good-quality infrastructure, places like Ballyfermot and Drimnagh have been left behind,” says Dempsey. “So it’s about catching these communities over what’s already there in other areas.”

While acknowledging that some areas look set to get more cycle lanes than others, Pidgeon, the Green Party councillor, says he just wants to see the planned network built.

“There’s huge changes coming and a part of me wants to improve them and make them right, but I don’t want to put any more roadblocks up, we need to just start building good cycle infrastructure everywhere,” Pidgeon says.

Ryder, of the Dublin Cycling Campaign, suggested he’d like to see the network built out faster.

“I think the council are doing what they can do,” he said, “although it’s not as fast as anybody would like.”

Would people in Ballyfermot cycle more anyway, if more lanes were built there? It depends on whether they were good quality and well-maintained, says Dempsey.

“The truth is that the cycle lanes in Ballyfermot are already underutilised and that’s not because there are no cyclists, that’s because people just do not feel safe cycling,” he says.

Because of construction along the Ballyfermot Road, sections of cycle lanes protected by bollards are “full of boulders, rocks, dust from construction and building sites”, he says.

“People in Templeogue probably cycle quite a lot because there is good infrastructure there,” he says. “You will not cycle if it’s not encouraged by good public infrastructure.”

Even despite the obstacles, Jackson, the independent councillor representing Ballyfermot-Drimnagh, says the numbers of people cycling in the area are increasing.

“Nothing like the level of people who use cars,” Jackson says. “Because for a lot of people cycling will never, you know, will never trump the opportunity to use a car or to use public transport because of people’s age profile, etc.”

But for people who are able, he says, cycling is becoming more popular.

“We have one school in Ballyfermot that has nearly nearly 1,100 students in it,” Jackson says, referring to St Michael’s, St Gabriel’s and St Raphael’s at the corner of Kylemore and Ballyfermot roads.

About two years ago the council put in secure bike parking, and also bollards that look like giant pencils, to keep people from parking their cars on the footpath at the drop-off and pick-up area, Jackson says.

“And that has led to a big improvement in the level of kids cycling,” he says. For most people, it’s not an identity thing to not cycle, he says.

“I think people are wrong” about that, he says. “When you do provide it [cycling infrastructure], if people feel it’s safe, people will start to see it as a potential option.”

“There are some people who you will never encourage, but I have to say, where we do provide the infrastructure, we have lots of kids now cycling to school,” he says.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.