Smears and threats against lawyers representing people seeking asylum ramp up

“Solicitors play a vital role in the administration of justice and any threat to them is an attack on the legal rights of every person,” said a Law Society spokesperson.

Harikrishnan Sasikumar’s exhibition of photos of these objects, At Home in Ireland, is on display now at The Hive at DCU’s U building.

On Saturday afternoon, a sticker on a traffic sign at the entrance of Hazelcroft Road in Finglas said “BEWARE OF THE IRISH” over a line in the shades of the Irish tricolour.

A flag rolled and danced on almost every lamppost on the road. They sprouted from the houses, too.

Dublin City Council is considering what to do about these flags, its chief executive has said, which have flown since April around Finglas. And in other areas, too.

The show of flags copies similar moves by the anti-immigrant movement in the United Kingdom, spearheaded by the likes of Stephen Yaxley-Lennon.

It also follows a regular appearance of racist graffiti in the area, says People Before Profit Councillor Conor Reddy.

One image taken in the neighbourhood shows a racist slogan that features the n-word written on the ground.

It’s been very upsetting for immigrant locals, who have written to Reddy, he says.

“It’s quite disorientating.”

Meanwhile, in nearby Glasnevin, Harikrishnan Sasikumar – a post-doctoral researcher at Dublin City University (DCU) – is displaying a sprawl of photographs showing objects in immigrants’ homes that embody their Irishness.

There are no flags in the final selection, but he had heard from someone who did keep one at home, said Sasikumar. His callout asked for participation from non-Irish people, but new citizens also wrote, he said.

“They were new Irish, but they had enough people telling them you’re not Irish,” he said.

Academics say immigrants have always been reminded that they are not part of the nation, even if they have lived here for a long time or have become citizens. In big or small ways, in the language used in official forms, and in hardened family reunification rules, they say.

Flying the flag as a way to exclude makes reminders of unwantedness just that bit more inescapable, they say.

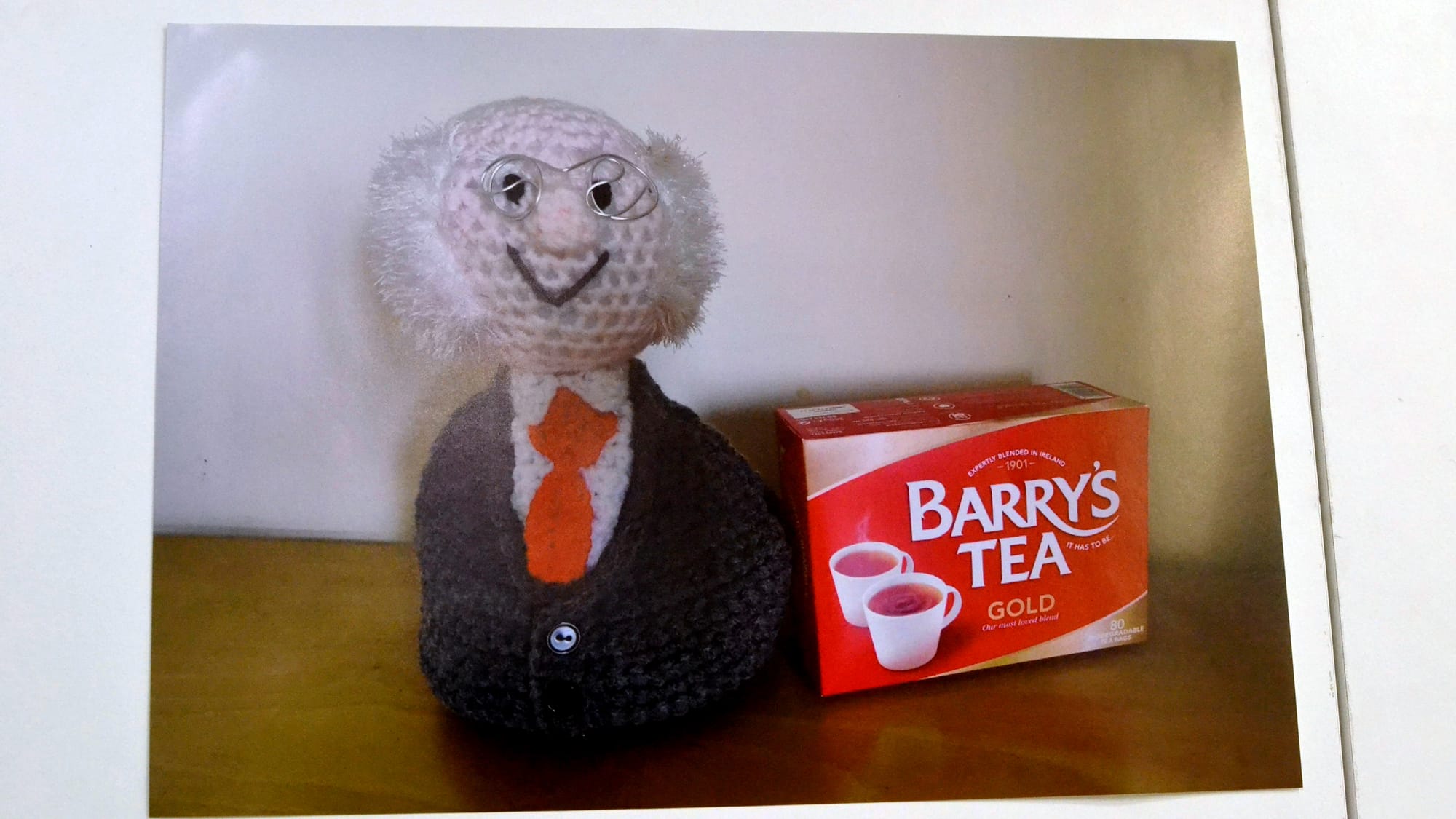

In Sasikumar’s exhibition, At Home in Ireland – currently on display in The Hive at DCU’s U building – one image shows a smiley crocheted Michael D. Higgins sitting next to a box of Barry’s Tea.

That’s from the home of Sheila Castilho, who was born in Brazil and lives in Drumcondra. She loves the president and drinking tea, Castilho wrote in her submission.

“Michael Tea Higgins is for me the most Irish thing I own,” she wrote. “I feel Irish every time I look at it.”

Another image shows a drying rack holding clothes in the home of Sahar Ahmed in Rathfarnham.

It’s always teeming with washed clothes because it takes so long for them to dry indoors, a constant feature of living the Irish life for Ahmed, she wrote.

“This indoor drying rack makes me feel more Irish than any passport ever could!” she wrote.

Alessandro Accogli, who lives in Smithfield, holds dear a fat green porcelain vase hand-made in a pottery studio in Co. Waterford by her partner’s father, ceramist artist Marcus O’Mahony.

A photo of the vase shows faded threads, like prickling veins, covering its surface.

“Looking at it takes me back to time spent in Marcus’s studio in Lismore, to his kiln, to the rhythm of both finished and unfinished pieces, and to the ever-present atmosphere of Irish creativity and craft.”

An email from a council official posted Friday on anti-immigrant Telegram channels asks council workers to prioritise gathering information on their whereabouts and urgently report back.

A council spokesperson has not yet responded to queries sent Saturday, asking what it has decided to do about the flags, if anything.

But on Monday, in reply to a question from Labour Councillor Darragh Moriarty, Richard Shakespeare, the council’s chief executive, said this is a “sensitive issue which requires a considered response”.

The risks are being weighed, he said, and area managers are meeting with senior Garda and local representatives in the coming week “to discuss the issue before any decisions are taken on the best way to proceed”.

In the meantime, the council is also working with councillors on thinking up a solution, Shakespeare said.

Meanwhile, some anti-immigrant activists seem to be already preparing to resist if the council decides to take them down.

Andrew Quirke, creator of the Dublin comedy act Damo and Ivor – who’s become an online anti-immigrant and anti-vaccine influencer in recent years – published a large picture of the council official who sent the email, saying if the flags were to be taken down, he’d go into “overdrive across Ireland”.

But some Finglas residents would be happy enough if these flags were removed, says Reddy, who represents the Ballymun-Finglas local electoral area.

He says he’s been getting emails from residents who aren’t thrilled about excessive flag flying in their area.

“Just even the aesthetics, with the wind and the rain. They get tattered and brown-looking,” said Reddy by phone. “We know what country we live in; we don’t need constant reminders that we’re in Ireland.”

On Saturday’s rainy afternoon, a drenched flag was stuck around a lamppost.

Threads of mini tricolours hung from a house on Hazelcroft Road. Just under its rooftop, it said on a larger tricolour: “You Can’t Beat the Irish”.

A flurry of flags lined the stretch of nearby St Helena’s Road, too. One tricolour standing on a house on the street danced over a Jolly Roger pirate flag.

Reddy, the People Before Profit councillor, says he is in favour of taking down the flags in Finglas.

He can feel tension and trouble welling up in the air, strolling on and around Hazelcroft Road, he said.

The council should have been more proactive before the situation escalated, he said.

He believes flying flags from lamp posts counts as littering, Reddy said.

The Litter Pollution Act 1997 has rules around displaying “any article or advertisement” from places like poles, doors, gates and windows that are public-facing.

On Tuesday, Moriarty, the Labour councillor, said he’s had mixed responses from council officials about the legality of excessive flag raising without permission.

“Depending on who you were speaking with,” he said by phone.

He said he’s been demonised online for speaking against it publicly, when it seems clear that the intention of some recent flag flying is to exclude people, sometimes accompanied by racist stickers or graffiti.

That the campaign follows a similar one organised by English nationalists in the name of Irish patriotism is ironic and problematic, said Moriarty, and he’s baffled that this is lost on those putting up flags.

Joe Mooney, historian and community activist in East Wall, said the tricolour affair is orchestrated and “manufactured” by anti-immigrant organisers in conjunction with ringleaders in the United Kingdom who are flying the Union Jack in part to foment a reaction and publicity around their takedown.

That’s why he feels conflicted about saying they should descend. “It’s a win-win situation for them,” he said.

“If the flags are taken down they would present themselves as victims of anti-Irish, you know, oppression, which is complete and utter nonsense,” said Mooney.

Then again, Mooney says, he’s a White Irish guy, and not one of the people those tricolours meant to exclude and intimidate.

“I know what it was like when my family lived in England and people would wave Union Jacks at them,” he said.

Says Moriarty, the Labour councillor: “It feels like a trap. They’re looking for the visual of a city council staff member or subcontractor taking down the flags to film them and spread like wildfire on social media.”

There could be a solution in posting reassuring, welcoming messages on the poles featuring tricolours, says Mooney.

Similarly, some anti-racist community activists have been carrying or flying the tricolour as a way to “reclaim” it.

Back in July, Damien Farrell, who lives just off James’s Walk in Dublin 8, pointed to a few flags around the neighbourhood, saying he noticed whoever had been mounting them had avoided the lamppost outside his street – so he put up his own tricolour.

Sasikumar, the DCU researcher behind the At Home in Ireland exhibition, says there’s nothing inherently wrong with "performative nationalism” such as displaying flags.

“The intention with which it’s being performed is important,” he said.

But not taking down the flags proliferating in Finglas and other areas also means the flag fliers are treated as if they’re above the law, says Mooney.

A few years back, when he and other locals raised banners advertising a play in the local community centre, the council took them down, he says.

“We put them up on the bridge at Fairview, and they were taken down. We weren’t happy about it, but we had unbeknownstly or carelessly breached the laws around hanging signs,” Mooney said.

Earlier this year, Lorenzo Posocco, a nationalism and immigration academic, co-wrote an article with Iarfhlaith Watson, an associate professor of sociology at University College Dublin (UCD), exploring the erosion of national identity in Irish society a century after it won independence.

While being Catholic and speaking Irish have long been markers of Irishness, fewer people practise the religion and speak the language now, they write.

There’s also been “a weakening of shared commitment to civic markers such as citizenship, political institutions, and laws”, they write.

“Looking ahead, the challenge for Irish national identity will be reconciling its symbolic endurance with the practical implications of its hollowing out,” they write.

In this context, some exploit the “flexible” nature of nationalism to promote a violent exclusionary format of it, Posocco said on Friday on a video call.

In Ireland, he says, the government’s failure to address the housing and cost of living crises and issues around access to healthcare also erodes national pride as citizens feel ill-treated by those in charge.

“The way they react is that, you know, they turn to extremist ideologies,” said Posocco.

Mary Gilmartin, a geography professor at Maynooth University, says none of this is new.

There has been momentum around this kind of nationalism before, which came to a head with a referendum that stripped children of undocumented people of the right to citizenship by birth in 2014, she said.

A 2002 letter to the editor in the Irish Examiner from Vincent McKenna of “Residents Against Racism” criticises then Cork Fianna Fáil TDs Noel O’Flynn and Batt O’Keeffe for “giving out about asylum seekers” as a way to garner votes.

“It seems playing the race card works wonders when it comes to wooing some of the more hard-line voters,” wrote McKenna.

O’Flynn’s son, Kenneth, who ran as an independent and became a TD last year, has also taken an anti-immigrant stance.

Politicians, seeking ways to conjure support, have always latched onto divisive movements like that to gain political power, says Gilmartin.

“Whether Ireland moves toward a more inclusive, civic-focused national identity or experiences increasing fragmentation and disengagement will depend on how these

evolving tensions are negotiated in the years to come,” says the paper co-written by Posocco and Watson.

In a 2012 column for the City Tribune, writer Charlie Adley recounted how watching two little “Indian” girls clutching a Union Jack in the Tube in London on their way back from an Olympic game stopped him short and calmed his contempt for flags.

“For those few precious moments on that tube train, all was right with the world,” he wrote.

“How long will it be before a similar Indian family in Galway City would feel proud and comfortable and so wholly included that their children would not raise a single eyebrow waving the Irish flag?”

Mooney, the community activist in East Wall, says the Indian community, holding vigils in response to recent reported episodes of violence, had also brought tricolours to show they are proud to be here.

If people and governments could accept that someone who lives in a country is part of the nation, then the focus could’ve been shifted towards working to overcome shared struggles and finding pride in small community triumphs, said Posocco, the academic.

“You’re a person, that’s enough,” he said.