What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

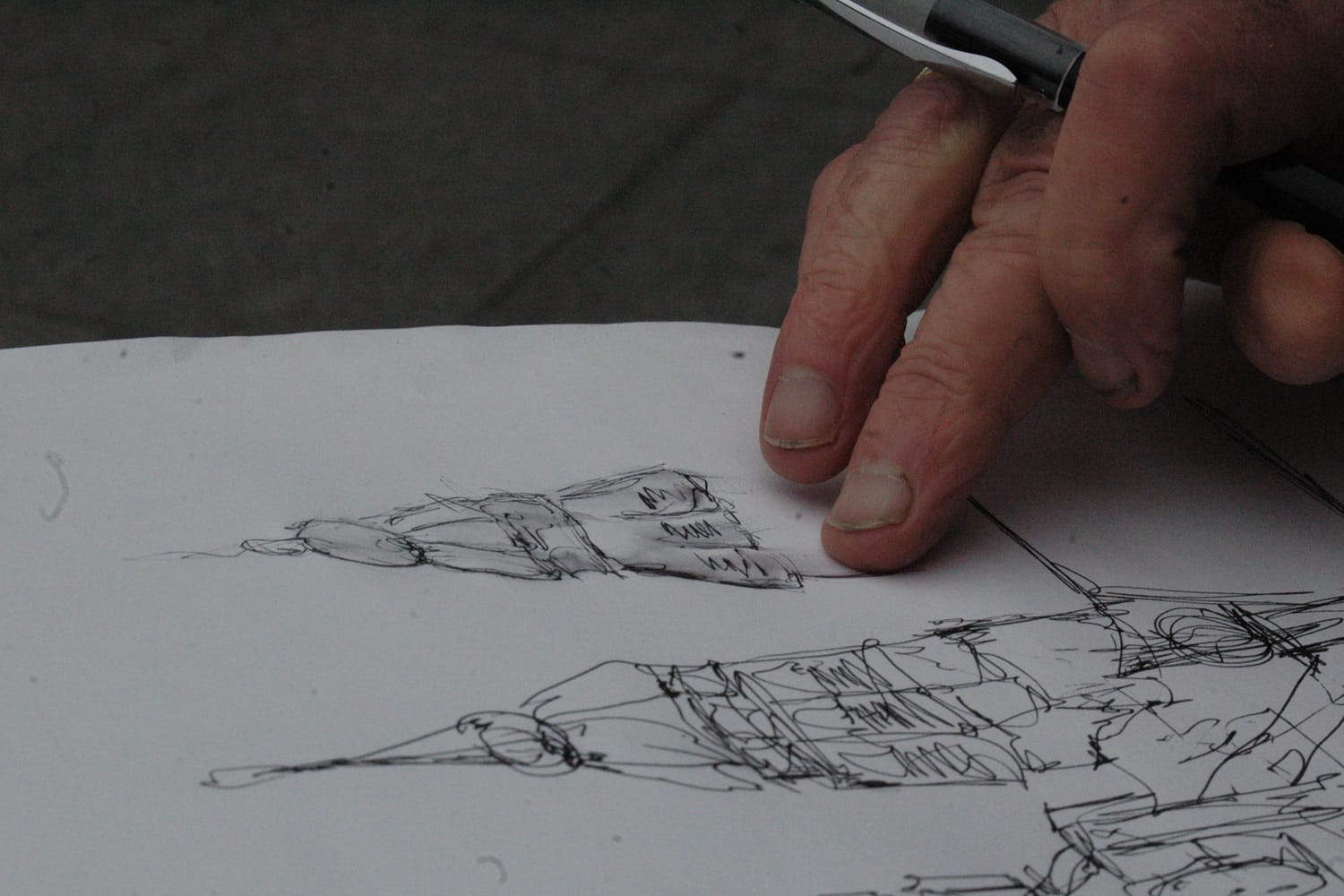

With a pen, “you can’t mess around. You can’t rub it out. You have to go for it,” he says. “I love that bit of danger.”

John Carpenter was leaning against the railing outside a terraced house at the corner of Pearse Grove, a cigarette in one hand and a sketch pad in the other.

He had been eyeing up St Andrew’s Resource Centre, with its yellow brick and curving Dutch gables.

It was built in 1895, according to the gilded numbers on its red sandstone peak.

He adores sketching the city’s old architecture, he says – and especially roofs. “You know, even when I’m walking down Henry Street, if you look up the top of the Penney’s building. It’s amazing.”

The pensioner, children’s author and art tutor’s reputation as a local artist with a keen eye for the architecture around Ringsend has been doing the rounds.

Susan Gregg Farrell had been searching for an artist to draw the Poolbeg chimneys and the local church for the community centre memorial wall.

She had put the feelers out on a local Facebook forum the Friday before. Carpenter’s name came back again and again.

Carpenter flips through his pad of sketches and watercolours. Figures laze on Sandymount Strand. Figures wait by bus stops, all around Ringsend and Irishtown.

Like one of his major influences – the Mancunian street artist L.S. Lowry – Carpenter draws with a pen.

He began to favour it after a session sketching the canal, he says. “I had a pen. I had a pencil. I was doing the locks with a pencil.”

Somewhere around Mount Street Bridge, he dropped the pencil, he says. “So I only had the pen and you can’t mess around. You can’t rub it out. You have to go for it.”

“I love that bit of danger,” he says.

Sometimes, Carpenter gives his work the soft touch of watercolours.

He turns the page over to show the terraced homes as they wind along Bath Street, the fronts of the homes washed in pale blues and yellows.

That’s where he lives, he says. “My wife was in the dentist, so I took a half hour and did this yesterday.”

But mostly, his work is bold black pen and frenetic scratchy lines.

Carpenter grew up across the city on Francis Street, he says. “Went to Francis Street School, went to Clogher Road Tech.”

And he had done well at Clogher Road Technical College in the early 1960s, he says, particularly in art. “Then I went to the careers guidance officer and he said, ‘Aw yeah, absolutely: fitter-welder.’”

Art school wasn’t something he considered at all, says Carpenter. “That wasn’t going to happen.”

“So I went off to become a fitter-welder, and I hated it. Working in ceilings. Putting radiators in hotels. Working on the American embassy,” he says.

He joined a few bands in the 1970s, performing in clubs like Sloopys and Club Arthur, he says. “Then I jacked up the job and got a job in retail.”

For more than 30 years, he worked in sales, until a heart issue in his mid-50s prompted him to get back to drawing, he says. “I just started again, getting gigs, doing classes.”

Carpenter made a name for himself during the pandemic. He used the time in lockdown to create a children’s book.

A Chimney Adventure was inspired by news reports about how the iconic red and white Poolbeg Chimneys were facing demolition.

A fictionalised version of Carpenter himself hatches a scheme with his two Cavalier King Charles Spaniels to turn them into an amusement park.

He would sell it outside Books on the Green in Sandymount, says Brian O’Brien, the shop’s owner. “He’d do a few Saturday mornings out there with the dogs.”

It was his first and last book, Carpenter says, and he hasn’t gone near the chimneys much since. “I’ve done them a few times. But I’m looking for something a bit more quirky.”

“Wait Mr Bus!” said a woman in a puffy coat, walking briskly past Pearse Square after a bus that looked set to leave.

Carpenter looked up from his sketchpad.

“I’m talking to the bus,” she said in a flat monotone.

Carpenter was now across Pearse Street, a better position for his sketch of the St Andrew’s Resource Centre.

Leaning against one of the pillars by the gate into Pearse Square, he drew a speedy outline of the centre’s gables and white cupola. He wet his thumb to smudge the ink, shading the building.

Once he had left his sales job, Carpenter started to tutor people of all ages, he says. He taught them about L.S. Lowry, did classes on manga.

“You’ll see kids who are very good, and then you’ll come across people in their 60s who say they were told in school they were no good,” he says.

He sees so much talent, stifled for years, decades even, he says. “They’ve been robbed a little bit. Sixty years of age and they say they can’t do it. But they can.”

There’s a young lad, about nine years old, who he’s been teaching recently, he says. “He plays football. I believe he’s very good. But he doesn’t have to be a Ronaldo, otherwise the pitch’d be empty. It’s about going out and enjoying it.”

Carpenter glances up at the roof of St Andrew’s Resource Centre. His style has a looseness to it at the moment, he says.

He kept his pen on the page as he added vents to the round cupola, keeping a flow, with the occasional inky squiggle to give the building more personality.

A single take, he said, pen nub still pressed against the paper as he moved it about. “You just sort of run with it, and I want to hold onto that.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.