What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Michelle Boyle’s show “Outside the Urban” is on at Axis Ballymun until 24 August.

In the 1980s, there was a vote on where Cedarwood Road was, exactly.

Was it in Ballymun? Or was it in Glasnevin North, perhaps? Or part of one of the other neighbourhoods that spread out around it.

The exurb seemed unsure of itself. Locals disagreed over where they were.

“It was so divisive,” says Michelle Boyle, an artist who lived as a child at 102 Cedarwood Road in the 1970s and 1980s. “I guess I felt I was mirroring that in my own sense of identity.”

Boyle had been adopted at a young age. She grew up mixed-race in a largely white neighbourhood.

“There was an oddness of that. I did feel on the outside of things,” she said, on a recent Monday at the kitchen table of her home in Virginia in County Cavan.

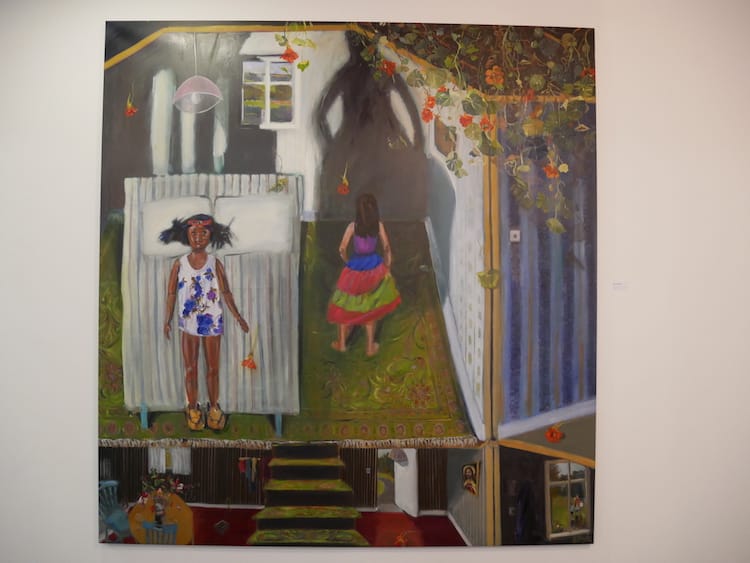

In the exhibition “Outside the Urban” – which is on at Axis Ballymun until 24 August – Boyle explores her uncertainty about her identity during her early years, and her resolution of that through a search for her birth parents and discovery of an Indian inheritance.

Boyle had little formal training in how to draw and paint, she says.

As a child, she would take the 19N bus into town for free drawing classes at the Hugh Lane Gallery on Parnell Square. “That was where I learnt to draw,” she says. “With big sheets of paper on the ground.”

In later years, she would travel to galleries and sit in front of paintings to reflect on how the artist had constructed them. “That has been my art education,” she said.

Boyle says she thinks a lot about the difficulties that those born and adopted in Ireland have in tracing their pasts. As she was born in England – and sent to Ireland for adoption – it was easier for her to find her birth parents, she says.

Since her paintings are hanging on the walls of the Axis Ballymun, Boyle flicks through images of them on the laptop on the kitchen table as she explains where they came from.

One, Strangers now, foster children, is of a woman, with a blank and emotionless face, in a huddle of babies. There are three bunched at her feet. Another three in her arms. It is painted in muted pinks, blues, and browns.

The painting is based on a photograph, Boyle says. She heard a man on the radio name a foster home in Donabate and recognised it from her adoption papers. She had been there as a baby.

She hadn’t known about the place and learnt only later that it was a badly run private institution. “The children were very neglected and starved,” she says.

Boyle lived there for four or five months before her adoptive mother picked her out.

“It’s almost like an advertisement,” she says of the image. “These are the babies we have in stock at the moment.”

The title is a reminder, she says, of how tough it is for people who were in foster homes to get their records. Often, they didn’t even know where they were.

For Boyle, the exhibition and her works were one way to take control back from those who would refuse to share what they held of others’ memories.

“For me it felt very important was that I created a visual record of a history that I didn’t feel I had any ownership to,” she says.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Cedarwood Road felt neither urban nor rural, she says.

Her adoptive parents came from Donegal, she says. “So they were rural people, as were a lot of other people on the road.”

Some of the paintings in the exhibition show her family stood in the garden, the landscapes of Ballymun with its fields and towers in the background.

The largest canvas shows her home at 102 Cedarwood Road, segmented as in a doll’s house. There’s a Sacred Heart on the wall, as there always was, she says.

A large Indian doll lies in the foreground of the painting. It was a Christmas present one year that became symbol of her confusion when she was younger over who she was.

She overheard her mother tell a neighbour that Boyle was half Indian, she says. Boyle understood that as Native American Indian.

It was only years later that she began to question that. “I was getting it all muddled up, it was getting confused.”

Aifric Ní Ruairc, the project coordinator at Axis Ballymun, said the exhibition reflects how the suburb has faced challenges in its own identity. “We have that here in Ballymun,” she says.

Now that the towers are gone, and with the landscape still blighted by the empty shopping centre, many in the community are still trying to figure out what the suburb is now, she says.

In her twenties, Boyle says she wasn’t too interested in tracking down her birth parents or wondering about where her origins lay. She travelled the world and was having too good a time, she says.

That changed in later years. “When I started to have my own children, it became an issue. Where I was from, and all that,” she said.

It took her eight years to track her mother to Mexico and when she found her, she wasn’t interesting in building a relationship. Her father in India, though, when she found him, was different.

“It took me on a very different journey,” she said. “For the first time, I recognised myself in his family and in his children. For the first time, I saw myself.”

“It was like drawing a circle around myself. It was for the first time feeling centred, and as if I had an identity,” she said.

That then opened up a whole new world, she says. “I hadn’t really realised I was half Indian, I hadn’t embraced that part of myself at all,” she says.

For the last five years, she has been going over to India to paint for periods of time and developing her work there.

Much of her work had always been about identity and absence, and the absence of a mother. But in the last couple of years, she has reconciled this, using her art as a medium to work through the issues that the blanks in her early life threw up.

Now she has several projects on the go in the spacious studios at the back of the house. One room has tables for yarn and other materials for days when she is feeling more tactile.

In another, she shows the larger “Incidental Icons” she has worked on. The portraits are painted on blocks of wood, inspired by the Fayum portraits of Egypt, and taken from the faces in the photographs that fill daily newspapers, which are disposed of as the news cycle moves on.

“There was something for me about giving a permanence to those images. It’s an ongoing project,” she says. The faces are anonymous, yet people can relate to them.

“The distance of space and time closes when you’re looking at an image,” she says.

She has also started to work a lot more in watercolours, she says.

She spreads out some watercolours on the large table in her studio: there are bright blue skies, and the sandy yellows of a Portuguese landscape. Some show the rocky shores of Maine, others the bright-green plants in an Indian garden.

Her work has changed with her visits to India, she says. She works more in watercolours because they are mobile so she can sketch and paint on the move, but also because of the vivid colours and the fluidity of the paint.

“It’s so giving, it’s such a beautiful medium to work in,” she says. “There’s definitely more of a joy coming into the work, I’d say.”

After tracking down and learning more about her birth parents, Boyle feels at ease. “I needed to know those things,” she says.

The change in sense of belonging can be seen in her work now. Going forward, she is more focused on other people’s narratives, she says. “It’s not about me anymore.”

The sombre shades and darker works of a decade ago have made way for more brighter colours, too. “I can’t anymore truthfully stay in that way of painting because it’s not where I am anymore,” she says.

Boyle has a background in archaeology and anthropology. So, she says, much of her education had focused on the impact of culture and context in making us who we are.

But she thinks slightly differently about it now as her relationship with parts of India grows. “There’s also a much deeper level of inheritance, I think,” she says.

It’s something she describes as almost non-verbal. “Is it possible that you can actually inherit a sensibility for a place? I definitely feel that,” she says.

Boyle says she has found a peace. But it struck her as she put together the “Outside the Urban” exhibition, that she couldn’t say the same for Ballymun.

The suburb still seems lost to her. She felt as if she has arrived in a place of knowing her identity. But “it’s terrible that a place can almost go through the same sort of traumas”.

The exhibition is showing at Axis Ballymun until 24 August.