What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Magda Mostafa’s ideas for Dublin City University, drawn up with the help of students, include a quiet area near the canteen, and swings where people can find a moment of calm.

Struggles with an immigration status, or a second language yet to be mastered, are invisible factors affecting one’s experience of buildings, says architect Magda Mostafa.

Add neurodiversity into the mix, and a building’s design – whether it’s an airport, a university or refugee accommodation – can silently diminish somebody’s sense of well-being, she says.

“And, as designers, we can play a really big role in bridging that,” says Mostafa, who has contributed to the design of a centre for orphaned autistic children in Ramallah, a city in Palestine’s West Bank.

Closer to home, Mostafa is also behind a new guide, with a series of proposed design changes at Dublin City University (DCU) drawn from guidelines she created for inclusive design mindful of the needs of people on the autism spectrum.

Malene Lyngsø Larsen, who studies English literature and history at DCU and is autistic, says that international students like herself are more at risk of not having safe spaces where they live.

“Therefore, it can be even more important for them to have a safe space on campus,” she said.

A spokesperson for DCU said, “the publication will be used to ensure future infrastructural developments at DCU are autism-friendly and to also retrofit existing buildings, where possible”.

Before walking into noisy areas on DCU’s campus, Larsen tenses up, she says. “Like putting on armour before battle.”

DCU has three sensory pods – soundproof boxes as wide as beds with options for light adjustment and music. But when there is no time to reach them, Larsen stays in warrior mode, keeping her invisible armour on all day, she says.

“If I have not had enough time to recalibrate from the day before, too much sensory input can create more cracks in the armour,” says Larsen.

“I always strive to find alternative routes that bypass crowded places, even if I have to walk longer,” she says.

Lao?ín Brennan, a biomedical engineering student and founder of DCU’s Neurodivergent Society, says he actively avoids the chaos at the canteen during lunchtime.

“It has big queues, unclear signage as to which queue is for what food, a loud machine for carrying trays to the kitchen,” says Brennan.

“I have felt, while in the canteen, lost, bewildered and in pain from a stress headache, exasperated by the constant, complex mixture of noises and motion,” he says.

Not everyone with what is known as sensory-processing disorder has autism, but many do. These sensory issues can make some people experience auditory, visual or other stimuli in a heightened way.

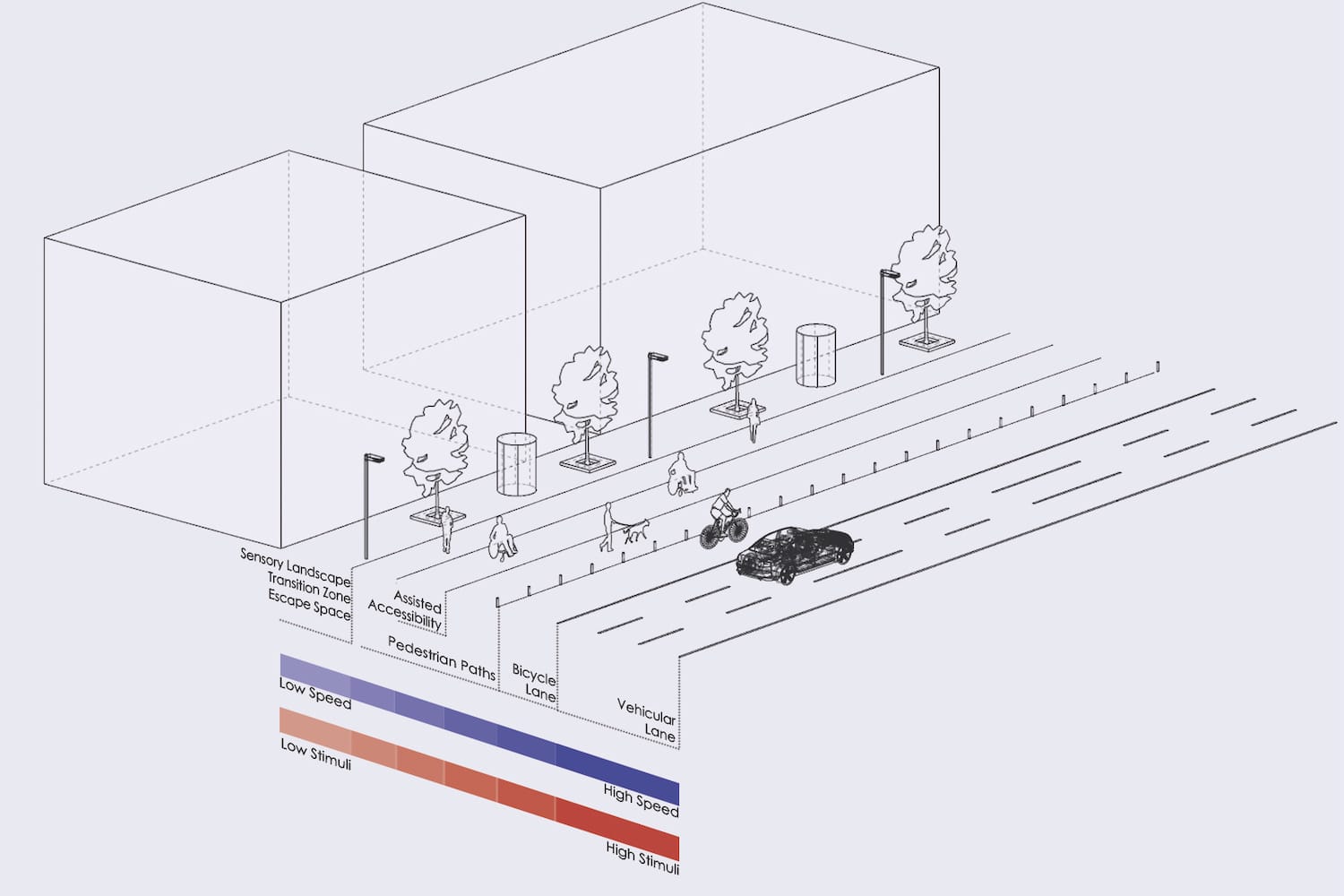

In DCU’sautism-friendly university design guide, Mostafa has identified sources of unwanted stimuli on campus, proposing simple design changes to fix them.

She’s used an index she created called the ASPECTSS™ design index, each letter standing for one principle.

“The outside area of the canteen is unutilised, could be used as a covered outdoor eating area to be a quieter place for the autistic community,” says DCU’s design guide.

The autism-friendly solutions in the guide will be applied to a proposed student accommodation on-site, DCU’s common student area, and parts of campus, including the canteen and cafeteria, Mostafa says.

Autism-friendly architecture is still a fringe movement, but Mostafa says she hopes it would go mainstream because mindful architecture intended to help one disadvantaged group often ends up helping many.

“Adopting the ASPECTSS index and a lot of strategies that we put in place actually benefits other groups too,” she says.

Autistic students are more likely to drop out of university, and sensory overload on campus is one reason they do, found a recent UK study by researchers at the University of Stirling and Royal Holloway, University of London.

“Although participants had different sensory aspects that affected them, common sensory challenges were noise and processing movements of people,” the study says.

Ian Lynam, an information officer for AsIAm, the Irish autism charity that reached out to Mostafa first about creating a design guide for DCU, says autistic students – like any other students – can be intense and passionate about the subject of their studies.

Supporting them to stay and finish their education is worth it, he says. “While autistic people’s needs may change as they enter adulthood, they are no less autistic and support should be available accordingly.”

Mostafa, who is an associate professor at the American University in Cairo in Egypt, says she has made design changes in schools throughout her career that boosted the productivity not only of autistic students, but of their neurotypical teachers.

“The very first set of responses I was getting was from the therapist and teachers themselves because they could suddenly do their jobs so much better because they didn’t have to handle the background noise and the filtering out of distracting noises,” she says.

Mostafa’s ASPECTSS guidelines have also shaped the design of the Calm Zone, an autism-friendly area at University College Cork.

Mostafa is especially proud of the DCU project because it was led and shaped by the voices of autistic students, she says.

“We worked with their neurodiverse student organisation. I had autistic students in focus groups and design workshops that we did,” says Mostafa.

“The guide itself was peer-reviewed by autistic architects and autistic students and parents of autistic students.”

Autistic people are so used to making minor adjustments to space to make things easier on themselves that they have gained a wealth of knowledge about space solutions and reconfiguration, she says, “that throughout my work I’ve always drawn from”.

Larsen, the international student at DCU, says her ideal campus has shortcuts to avoid bustling areas and spacious lecture halls where her personal space is respected.

For Brennan, founder of the university’s Neurodivergent Society, an ideal campus means plenty of quiet space and lots of greenery.

“I love trees,” he says. “Given my way there would be access to benches, tables and shaded areas under trees between buildings and a larger area at the end of campus that has least passing traffic with more extensive green space.”

Mostafa’s illustrations for DCU show an “escape space” near the green areas of campus. There would be swings on campus, too, another useful escape for autistic people, she says.

“Swing is a tool that can be used to provide an escape for individuals that are on the spectrum. Particularly, if it’s an individual swing, it gives you a space that’s just your own for the moment,” she says.

One can rock back and forth on a swing, another way to calm the mind into efficiency for autistic people.

“Autistic individuals, one of the self-stimulation things that they do is to rock or to flap or to bounce or to be on their tippy-toes, and that sometimes means that they are craving that kind of vestibular stimulation,” Mostafa says.

Mostafa is not big on calling it a design mistake, but she says inattention to acoustics is where designers often fail autistic users.

The “A” in acoustics makes up the first letter and principle in Mostafa’s ASPECTSS design index. But many designers these days tend to pay laser-sharp attention to visuals, she says, ignoring the way sound is transferred and echoes within a space.

“Unfortunately, architecture has become a very visual act, and it’s all about the image, and it’s the Instagrammability of a space,” she says, smiling.

Mostafa has a real-life example to drive her point home. At a meeting about autism once at a global health organisation alongside an autistic colleague, she saw someone who was otherwise articulate and precise struggle to be himself because of the auditory overload in the environment.

“He was shut down and unable to really participate,” she says.

In autism-friendly design itself, lack of diversity can be problematic too. That’s assuming all autistic users are stuck in one stereotypical mood all the time, says Mostafa.

“I think you have to think along the spectrum, and even a single autistic person themselves doesn’t have the same needs every day. Like all of us we have our days and our moods and triggers, we have our moments that influence how we feel within the space,” she says.

Adam Harris, the CEO and founder of AsIAm, says he’s hoping that autism-friendly design becomes a standard process in any architectural project in Ireland.

Having more autistic workers and policymakers across the board would help to achieve that objective, he says, but a recent study carried out by AsIAm and IrishJobs.ie showsthat autistic people struggle to land jobs.

There is a lot to be done to make recruitment practices more accessible, says Harris. “I think when any minority is excluded from any aspect of society, that insight is going to be lost. That’s why diversity is so important.”

“It is really about bringing different perspectives to the table, and with these perspectives, you’re actually designing better for everybody,” he says.

Mostafa likes to encourage all designers to keep looking back at finished projects and ask for feedback on how users experience them.

“I think it’s important as a designer to have the courage and honesty to constantly look back at your work,” she says.

DCU is going to make its autism-friendly design guide available to “all higher education institutions in Ireland and further afield”, they said.

Some of Mostafa’s projects, including her work with DCU, are currentlyon display at the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.