What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Last month, staff at the Guinness archive discovered this 19th-century map of the city’s drinking establishments.

Guinness archivist Fergus Brady leads the way past visitors gathered near the staircase below, and into a small room that faces out onto James’s Street.

A map is laid on the table nearest the window – one of the 200,000 items held at the archive at St James’ Gate. It’s in pristine condition, between two thin plastic sheets.

Red dots mark dozens of locations around Dublin in 1892. This is, its title announces, a “MAP SHOWING DUBLIN’S GREATEST EVIL (PUBLIC HOUSES)”.

When they discovered it last month, says Brady, “(they) had a good laugh. Why does Guinness have an advertisement against Guinness?”

Some Dublin neighbourhoods were littered with pubs back then, it seems. There are clusters of red dots either side of the Liffey.

There’s “absolutely loads on Thomas Street and James’s Street”, says Brady, pointing to a clump of red dots there.

Public houses had spun off from the distilleries in the Liberties that had earned that part of the city the nickname the Golden Triangle, he says.

Brady points to the bottom of the map. “It shows that Guinness were aware of the bad guys, from their perspective,” he says. It wasn’t themselves.

The map was printed, he says, by the Dublin, Glendalough and Kildare Diocesan Association of the Temperance Society. And it wasn’t so much beer that they look to have been targeting, as whiskey.

In 1892, beer was seen as a more modest poison than whiskey, says Brady. “So Guinness tapped into that and were able to portray themselves as purveyors of a much more wholesome beverage.”

Some on the Guinness board in 1892 were members of the Church of Ireland too. So, they may have looked “favourably” on a temperance map, says Brady.

Guinness, owned by “temperate, thrifty and industrious Protestants”, approved of moderation, writes historian Diarmaid Ferriter in A Nation of Extremes: the Pioneers in Twentieth-Century Ireland.

“It’s trite to assume that all brewers and distillers saw it in their interests to preside over a drinking culture predicated on excess,” Ferriter writers.

Father Theobald Mathew founded his teetotal society in 1838 and encouraged people to take a pledge not to drink alcohol. But by the end of the 19th century, most temperance reformers backed changes in Ireland’s licensing laws as the route to tackle the demon drink, writes Ferriter.

It wasn’t a just a debate going on in Ireland at the time, but all around the world. The map ties into that growing global movement, which most famously begot prohibition in the United States from 1920 to 1933, says Brady.

By 1892, Dublin city had a total of 747 licensed premises, each marked and “shewn thus” by this temperance map.

Six years later, James Cullen, an Irish priest, founded his Pioneer Total Abstinence Association, commonly known as “the Pioneers”.

A handful of these pubs still serve Dubliners today. (You can see a larger version of the map here.)

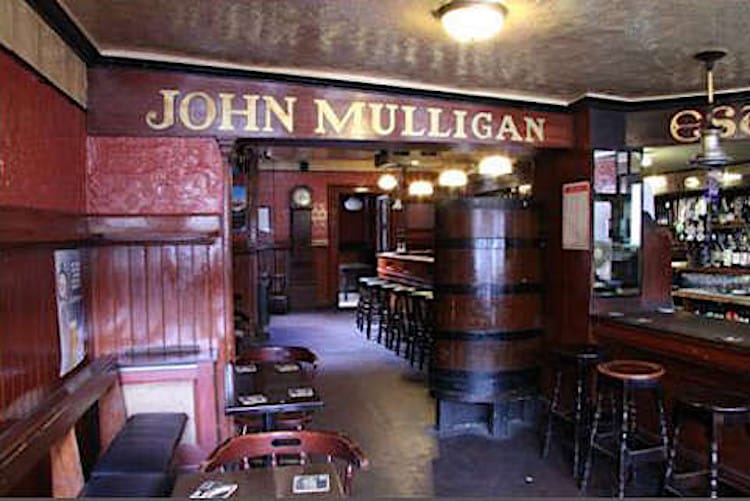

On Poolbeg Street, a red dot marks Mulligan’s pub. Operating since 1782, says manager Gary Cusack, little has changed.

Similarly, the Swan, marked by a red dot at the corner of Aungier Street and York Street, “hasn’t changed much”, says manager David Forte.

It was originally constructed in 1661 as a tavern, says Forte. The pub’s current furnishings were built in 1897.

“They say the safest drink was alcohol because you couldn’t drink the water in Dublin,” says Forte. “People came to public houses for refreshment, an awful lot of workers to cash their cheques.”

Arrests were frequent in the late 19th century, though.

In the top right-hand corner of the map, Dublin Metropolitan Police figures show that there were 11,651 arrests for drunkenness and 3,870 arrests for drunk and disorderly conduct in Dublin city in 1891.

Drunkenness can lead to more serious crimes, so can be hard to find in headline figures. But based on the best available data from the Central Statistics Office, the number of arrests for disorderly conduct in Dublin city in 2017 pales in comparison: there were 3,917.