What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

“This is a very visual place, and the poetry just illuminates that further.”

In a corner of the busy café in the Axis Ballymun arts centre, the centre’s programme director, Niamh Ní Chonchubhair, reminisces on the life of local poet and activist, Pat Tierney.

Known as the Bard of Ballymun, Tierney would stand at the top of O’Connell Street, Ní Chonchubhair says. There, he offered children 50p if they would create a poem on the spot.

The centre holds a collection of his writings, published and unpublished, says Clodagh Duggan, an actor and the Axis programme co-ordinator.

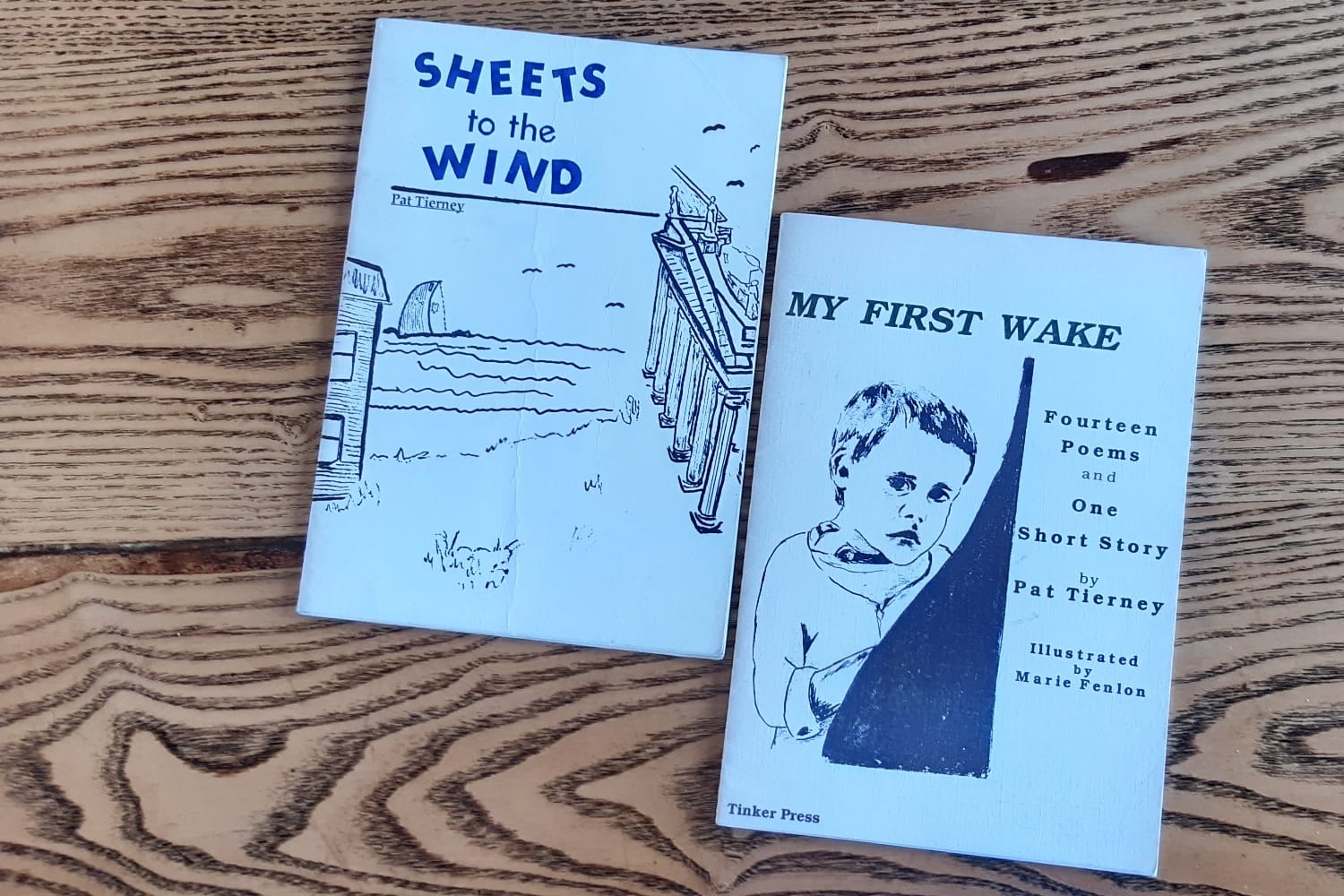

She hurries up to the centre’s first floor to grab two of his self-published poetry volumes, Sheets to the Wind and My First Wake.

The former’s cover features an illustration of the General Post Office juxtaposed with the sea and a two-storey house, the latter, a sad young boy.

Duggan is midway through preparations for the first Ballymun Poetry Day, due to take place on 30 June.

As part of the celebration, she and poet Chandrika Narayanan-Mohan have organised a project to commemorate Tierney’s life, work and impact on the north Dublin suburb.

Titled the Bards of Ballymun, the intention is to record and share the works of three poets, either local or who have chosen to write about the area’s heritage or culture.

“Poetry is really thriving in Ballymun,” says Duggan. “We wanted to make a piece that honoured that.”

Both the Poetry Day and the Bards of Ballymun project stemmed from what was a clear abundance of poets living in the area, Duggan says.

“We wanted to hear and see Ballymun through the eyes of different people. What it sounds like, what it feels like to them,” she says.

Herself and Narayanan-Mohan searched out writers who could represent the myriad facets of the suburb.

“The community garden is a big thing here,” Duggan points out, saying they wanted people who were exploring the area’s plants and often overlooked wildlife. “We received a load of poems about its nature and its sunflowers.”

They also looked for poets who lyricised aspects of the locale that were stigmatised, such as its seven tower blocks, constructed in the mid-60s.

“When they were put up or taken down, the smells of the towers, their sounds,” Duggan says. “There was one poet who discussed her mam going up the stairs even though she was afraid of heights.”

From the deluge of submissions that came in, Duggan says, there was a slew of images that came up again and again.

“It was the community coming together to eradicate that sense of loneliness felt through the lockdown, the nature of the area and its parks, things what people found solace in during isolation,” she says.

One of Duggan’s colleagues, Kate O’Neill, a marketing and sales coordinator interjects. Neither herself nor Duggan are from Ballymun themselves, she says.

“We were seeing Ballymun through other people’s lives,” O’Neill says. “We learn through them, and it’s such a mix of generations. This is a very visual place, and the poetry just illuminates that further.”

Among Ballymun’s most distinguishing landmarks today is the Rediscovery Centre, made from the refashioned former Boiler House, still with its red-and-white chimney hoops.

The striped chimney looms over the new facility, which promotes recycling and low-carbon living.

On its rooftop is a sensory garden. On one wall is a vertical garden. On another is a recreation of the 19th-century Japanese woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, fashioned from plastic refuse.

Waiting inside the centre’s main entrance is the poet Martin Holohan, one of the participants lined up to give a reading for the Ballymun Poetry Day.

A resident of Fingal and a local social worker, Holohan recently published his debut poetry collection, Hello Hinterland, which includes a piece called, “I Can and Will go out to Ballymun”.

Holohan reads the poem aloud, gesticulating with vigour, and speaking each verse with fervour.

“I can and will go out to Ballymun,” he says, his voice emphasising each verb.

“This is the future, the past is run/ No longer labelled with your wrongs, it done/ Ballymun now belongs to everyone.”

The poem nods to local characters, such as Ron Cooney, a music teacher featured in director Frank Berry’s documentary Ballymun Lullaby.

It is a piece he classifies as a work of social history, referencing certain streets, the Poppintree Park and the controversial, stagnant regeneration project.

Holohan says he spent years travelling the world, before becoming involved in a homeless charity.

He wrote on the side for a long time, but struggled to figure out a way to present his ideas. “Was it going to be a novel, what was it going to be?”

“The penny had been dropping slowly for a long time,” he says. “I hadn’t found my medium until I started to work in Ballymun.”

Ballymun, he calls, “a marvellous underbelly”. “This could be like Salford, attached to Manchester, and that is the place that produced the poet John Cooper Clarke.”

“Where you have an underbelly of poverty, or worse, people being told, ‘Don’t tell anyone you’re from Ballymun or you won’t get a job,’” he says. “That is what Ballymun is coming out of.”

“But when anything is forced underground, that is what gave us something like punk in the 70s.”

One of the people Holohan calls integral to bringing to light the spate of poets currently in Ballymun, is David Rooney, the organiser of Teapot Tales, a monthly poetry afternoon.

“He’s like the conduit,” Holohan says.

Rooney is a practising Buddhist from Marino, whose written output is often presented in a video format.

He combines illustration and painting with short dramas, part-autobiographical, and which interpret Buddhist teachings, notably one of the Buddha’s 10 principal disciples, Subhuti.

“I always loved storytelling and creating pictures from stories,” Rooney says. “But for me to make sense of something, I need to put a picture behind it.”

Fresh from an early morning visit to the Dublin Buddhist Centre on James Joyce Street, Rooney arrives at an Insomnia coffee shop on Talbot Street at 8am.

He says that he first went to Ballymun to open a business, which he operated out of its civic centre.

The business didn’t take off, he says. But he took to teaching tai chi and dance, before the Axis Centre encouraged him to stage an event that celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2021.

From this came the idea for Teapot Tales, which encouraged locals to read their poems, short stories or spoken-word pieces.

The sessions became a melting pot of people, whether they were social workers, accountants or students, he says. “They were looking to get back into writing.”

“It is all rough and raw,” he says. “But, like with myself, it’s from people who need this to come out of them.”

Says Duggan of the Axis Centre: “We’ve seen so many people come to Teapot Tales who are incredible poets, but who may not have had the confidence or space before.”

Tanya Ray, a local drug outreach worker, met Rooney through the civic centre and says he hounded her to read some of the pieces she had quietly worked on for several years.

“I was a bit nervous,” Ray says. “But it’s very supportive, and we had students from the Trinity Comprehensive School come along. It was absolutely amazing, the quality of their work.”

Outside the front gates of the Trinity Comprehensive School, four rectangular boards are mounted to the brick walls.

Greeting pedestrians as they walk into the centre of Ballymun, each one displays a poem and an accompanying work of art by Transition Year students.

“Read them,” says Holohan enthusiastically. He references one by Thembi Nkosi. “It has the line, ‘This is the performance of a lifetime, smile.’”

Nkosi talks about putting on an act for her friends and teachers, regardless of the pain she feels herself.

“She lists all of the performances. She gives like a shopping list,” Holohan says, “She does this act in order to graduate, and I mean, wow.”

Kate O’Neill of the Axis Centre, says it was fascinating to discover that the neighbouring school was teeming with such articulate young writers. “We had been unaware of those budding talents.”

The Bards of Ballymun project and the Poetry Day, she says, is to bring them out into the open.

“It’s to bring people like Pat Tierney out of the woodwork, whether they are new to poetry,” she says, “or whether they’ve been here for 40 years.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.