What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

The alternative media collective intends to put on events over the next few months to celebrate its legacy.

After seven years, 15 print editions, and thousands of social media posts, the team behind the non-profit alternative media collective rabble say they’re winding it up.

Responsible for gigs, merchandise, and a self-titled magazine, the rabble collective emerged from a network of young people who felt that the 2008 economic crash had robbed them of their futures, says Killian “Redmonk” Redmond, a founding member.

Club nights like Kaboogie, in the now-shut Twisted Pepper, were a meeting place for young people frustrated with the state of Ireland after the crash, and during the recession, he says.

Says James Redmond, another of the founders, and a driving force behind rabble, “We expressed a lot of what our audience were thinking and feeling, especially about the recession.”

“They didn’t see that reflected back in any of the other media out there, we wanted to give people something they could identify with.”

Those who got involved shared a sense of grievance that they had been stripped of promising futures after the crash of 2008.

They felt they’d missed out on the riches of the Celtic Tiger, says Killian Redmond. Most were coming out of college and finding their first jobs.

“It felt like if we can’t take things back through direct action, we can at least sort of critique what is going on and get that out to a wide an audience as possible,” he said.

Since it is a collective, everybody in the rabble camp “has a few strings to their bow”, says Killian Redmond. His main output was illustrations.

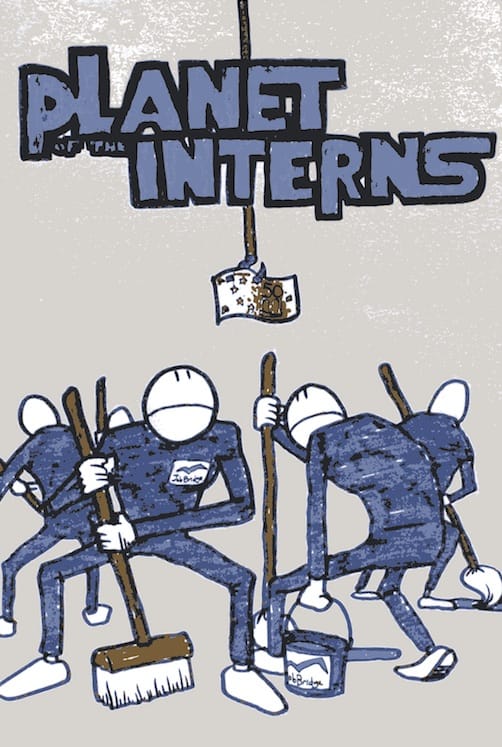

His favourite was “Planet of the Interns”. It depicts a group of interns in blue overalls bent over and mopping the ground – for the prize of a €50 note on a fish hook above their heads.

It was a shot at the JobBridge scheme that the government introduced in the years following the recession, under which people got a small top-up to their social welfare payments for serving as interns.

The dystopian 1984-esque perspective exemplified by the “Planet of the Interns” illustration is a hallmark of rabble magazine.

The rabble collective have no allegiance to any particular political party or doctrine. The publication was made by and for the generation left in the lurch in the years between the Celtic Tiger and the “recovery”, says Killian Redmond.

There was an atmosphere of apathy in Dublin when the recession kicked in, he says.

“People were confused, people didn’t know how to react to it, people didn’t see it coming and people were shocked then that bondholders were getting bailed out and everyone was getting bailed out except you know the bottom 90 percent,” he says.

“People were pissed off. The day-to-day news was so depressing a lot of people put their heads in the sand,” he says.

Rabble tried to give the voiceless a voice within Irish media. “There was a bit more … I don’t want to call it political awareness because it sounds like people subscribing to a certain political party or ideology. Party politics never came into it for any of us.”

Rabble went at topics like the anti-water-charge protests and the marriage-equality issue with no sense of compromise.

Every print edition had a featured “gombeen”, usually a political actor that the rabble team had decided was the most incompetent, which was the magazine’s way of taking a “potshot at illegitimate power”. In issue nine, in early 2015, that meant Labour Party leader Joan Burton.

Illustrations were often its weapon of choice. “The weird little looniverse of characters and cartoons that were created within the pages of the magazine is pretty remarkable,” says James Redmond.

Long before other publications copped on to the benefits of running activities offline, rabble were organising gigs and events.

More recently, they got an advert up in the stadium at Dalymount Park declaring the “system a fraud”.

“Seeing it pop up on so many goal highlight clip packages on RTÉ definitely spawns a personal chuckle,” says James Redmond.

At its best, rabble was probably “our best media incarnation of what resistance has looked like over the last decade”, says Harry Browne, a journalism lecturer at Dublin Institute of Technology.

That means “resistance to the hegemonic politics of the market, and especially to austerity”, he says.

It set a high standard visually, as well, Browne said. “It’s no slouch on social media either – though the resistance movements it has covered so well can easily speak for themselves nowadays, and therefore rabble’s excellent work may feel somewhat superfluous.”

Rabble was paid for through fundraising gigs, selling merchandise, and a once-off Fundit drive.

The team didn’t really have a business strategy, and the organisation was sustained through volunteers, as well as crowdfunding drives, merchandise sales and – most importantly – gigs with the Workers Beer Company.

“We would spend summers slopping out pints at festivals and pulling the wages back into the project,” says James Redmond.

A few good seasons with the beer company stopped them “nose-diving off a fiscal cliff for absolutely ages”, he says. But it also “contributed to a general malaise in terms of solving a funding crisis that was always brooding away in the background like a ticking time bomb”.

The Fundit campaign brought in €9,720 – enough to print four issues of the publication.

But nobody on the rabble team was ever paid for their work. And keeping up the project with volunteers became harder as time passed, as staff got older.

In February 2017, the team told readers they needed to find a way to “move the project towards a sustainable, structurally sound survival footing that covers all the costs involved”.

Not just the “fancy shit like bylines but also behind the scenes stuff like design, distro, editing and emptying the bins”, it said.

They surveyed readers, and decided to press ahead launching a Patreon, which has attracted 60 supporters and $322 a month.

Reader-supported journalism is viable, Redmond says. Patreon offers an easy way to do that.

But rabble’s Patreon wasn’t as successful as it should have been, he says. “Our own publishing rate had declined and you really need to be giving people something back on the well regular to keep subscribers,” he says.

Advertising didn’t work out, either. “We gave away more ads than we’d care to ever count,” he says.

Applying for grants and funding was a futile time-sink, he says. “I think by the end we were near convinced that those funding bodies exist just to suck up people’s time in applications and prevent them doing anything useful with themselves.”

Rabble decided to make issue 15 their last. Those behind the publication plan to focus on their own careers and, in some cases, start families, says Killian Redmond. (Full disclosure: one of the team has since joined Dublin Inquirer.)

“Personally, there comes a time when you want to work on other things, projects that don’t involve so many people and getting them across the line requires far less stress about having to coordinate that effort,” he says.

“We weren’t really getting the space to develop as a project, and when you can no longer see any horizons, sure then you are literally just falling to the ground,” he says.

In the months ahead, the collective want to celebrate rabble and its legacy. So they’re planning an art exhibition of some of the publication’s finer works, and a comic book of the best illustrations.

They are currently working through rabbles’s back catalogue to produce “some sort of posh-ass coffee table book”, says James Redmond, “that people can read on the jacks, use to fill out a Christmas stocking or batter their landlord with”.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.