What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

For hundreds still left without shelter and exposed to exploitation, hostility and violence, how much of a difference will that ruling make?

On Thursday evening, Hassibullah Bic sat on a low wooden stool inside a makeshift carpeted corridor between two tents.

A shabby sheet curtained the small hallway. An orange was at his feet, and some banana and orange peels lay beside a white electric kettle on the floor.

Bic laughed at the sight of a tape recorder and grabbed a pair of sunglasses, sliding them on.

A crowd clustered around an asylum-seeking member of the Revolutionary Housing League (RHL), whose right eye was black and bruised after a clash with a group of anti-immigrant protestors minutes earlier.

In Persian, Bic said he’s been homeless since arriving in Ireland about a month ago. The member of the RHL – a campaign group focused on occupying vacant properties – had brought him and a few others from Mount Street to the backyard on Sandwith Street Upper, he said.

These men were among more than 570 asylum seekers who, as of 4 May, had been left homeless, according to official figures. The government said it could not house them because of a shortage of accommodation.

In the yard on Sandwith Street, Bic said anti-immigrant protestors would often turn up at night and hassle them, not just that Thursday. “Looks like it’s better if I found somewhere else.”

By Friday, an anti-immigrant crowd had burned out the makeshift shelters. On Sunday, a video of people cleaning up the site circulated on their Telegram channels.

Almost a month ago, the High Court ruled that the Department of Children and Equality had violated a European Union law safeguarding the right to shelter for asylum seekers.

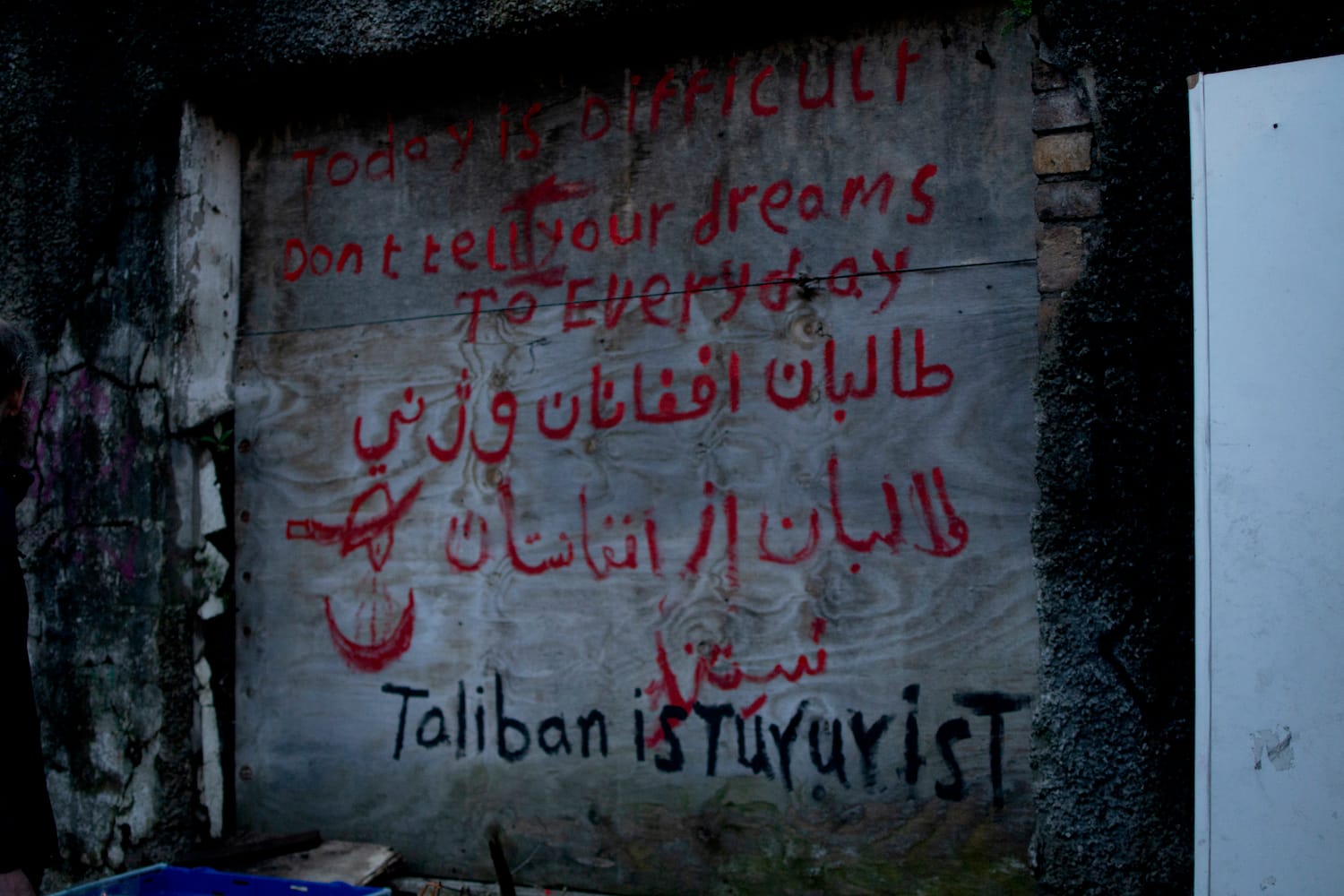

The High Court judgment focused on a 17-year-old Afghan boy who had come to Ireland after his father was killed by the Taliban and left to sleep on the streets here. “Whilst he was sleeping rough, the applicant felt constantly scared and in danger,” the judgment noted.

But for the hundreds still left without shelter and exposed to exploitation, hostility and violence, how much of a difference that ruling will make is complicated by the extent of the court’s powers and the willingness and capacity of the government to help.

Mohamed Tienti has been homeless for more than 70 days now, he said on 30 April.

He had a space in a city hostel, but was evicted. Clothes had gone missing, he says, and he complained to the hostel manager.

Gary Daly, a partner and solicitor at Daly Khurshid Solicitors, says people in situations like Tienti’s may be able to legally challenge the government’s failure to accommodate them.

But it wouldn’t be straightforward, he says. It would depend on how reasonable the courts considered his eviction from the direct provision centre, says Daly.

Under laws governing the rights of asylum seekers to housing, what is considered housing is broad, and who is considered homeless is narrow. And it’s more about shelter, than a home.

The government had met its legal obligation to house him, Daly said.

“The definition of homeless as extended to people born here is completely different than what we have for asylum-seekers,” says Daly.

For asylum seekers, the law only accepts them as homeless if they have no roof at all over their heads – no matter what the kind of accommodation – and the government has never offered them any, he says.

How the government defines homelessness – and who it counts as homeless – among those who live in Ireland and aren’t seeking asylum is also problematic. But in a different way.

The Housing Act 1988 says that a person is considered homeless if, in the council’s opinion, there is no accommodation they can reasonably be expected to live in.

If they live in a hospital or emergency shelter, for example, they are considered homeless, it says, and if they can’t provide for themselves out of their own resources.

Housing-rights charities have said that gives councils ultimate discretion to judge whether someone is homeless or not, and they can judge wrongly or push back against providing accommodation.

Daly also says that another difference between asylum seekers and others is that turning down an offer of accommodation is not an option for those who want to challenge the government in court over homelessness.

“Once the government gives you any kind of accommodation, anywhere in the 26 counties, they have complied with their obligation,” he says.

A spokesperson for the European Commission said on 28 April that it is aware of the recent High Court ruling that found the Department of Children and Equality in violation of European Union law.

“The Commission is in close contact with Irish authorities regarding the reception conditions,” they said.

It’s up to member state authorities to enforce the judgements of national courts, but the European Commission has been helping Ireland with “the management of migration” via funding, the spokesperson said.

It gave €79.5 million from 2014 to 2020 and €66.9 million from 2021 to 2027, they said.

Asylum seekers sleeping rough who haven’t been offered anywhere at all have clearer cases to take than Tienti, who was given accommodation and then evicted from it.

During the recent high-profile challenge by the young Afghan asylum seeker, lawyers for the Department of Children and Equality tried to argue that the judge shouldn’t hear the case because the government had, by that stage, housed him.

But in his judgment, Mr Justice Charles Meenan said that was irrelevant. Because the case was one of many, he says.

“Unfortunately, it appears that some or all of the “many” have not received the accommodation to which they are entitled,” Mr Justice Meenan said in his ruling.

Mr Justice Meenan acknowledged that the government had failed the applicant beyond housing by not meeting other basic needs under EU law.

When the young Afghan asylum seeker first arrived, social workers disputed his age, told him there was no shelter available, and gave him a voucher worth less than €30 for Dunnes Stores to buy bedding, the judgment says.

They told him to go to Capuchin Day Centre for homeless people on Bow Street to meet his basic needs, says the judgment.

“Clearly, giving the applicant a €28 voucher for Dunnes Stores and the addresses of private charities does not come close to what is required,” Mr Justice Meenan ruled.

Cathal Malone, an immigration barrister in Dublin, says off the back of that ruling, the government now has to provide more to homeless asylum seekers.

“No effort had been made to give that poor Afghan lad a sandwich, a bottle of water, a bar of soap,” Malone said.

The government had shrugged off its responsibilities, putting them on homeless charities, Malone said. That’s legally unacceptable, he said.

Malone says that if the state really wanted to house people quickly and get them off the streets, it could.

“I can open booking.com right now and book myself into the Shelbourne or a hostel,” he said on a phone call on Friday night.

One thing Ireland isn’t short of is hotels, Malone says.

“For the government to credibly make this case, they would have to actually aver in an affidavit that there weren’t 578 hotel rooms available in the state at any given night,” he says.

“So I don’t understand the accommodation argument, and if you leave accommodation out of it, the minister didn’t even put forward an argument as to why a sandwich couldn’t be provided,” he said.

In cases where the court finds an EU government in breach of European law, people can get compensation under the law – or what it refers to as “Francovich damages”, says Malone.

“And this is a sum of money that the country can pay to you for its clear and knowing failure to comply with European Union law,” he says.

But generally, it’s unfeasible for courts to ensure homeless people are housed or other similar things that involve heavy intervention in government expenditure and future follow-ups, he says.

“It’s generally inappropriate for the courts to tell the government how public money is to be spent because it’s a breach of the separation of powers,” he said.

Even if the courts did that, Malone says, then they would have to keep following up with the government to see if it complied with orders. “The courts don’t like having to have ongoing supervision like that.”

The High Court seems to be doing that in this case, though.

A spokesperson for the Department of Children and Equality said the government is already accommodating 84,000 people at the moment.

“This compares with 8,500 at the beginning of last year and is equivalent to the population of Galway City,” they said.

“Since the beginning of January 2023, more than 6,000 new beds have been contracted,” they said.

The government is doing whatever it can to provide more shelter, the spokesperson said.

“[Ninety-eight] people previously unaccommodated were offered accommodation over the weekend, and several large facilities are due to become available in the coming weeks.”

“Also, IPAS has an agreement with Mendicity to make its drop in day services [for homeless people] available to non-accommodated persons,” the spokesperson said.

They are able to access information, food, Wi-Fi and shelter there, they said.

“While demand continues to outstrip supply, particularly for adult males, the Department has managed to ensure that all families and children have been accommodated,” the spokesperson said.

It’s making use of every accommodation offer made to it to address the shortfall, even repurposed buildings and tented accommodation, they said.

Nick Henderson, the CEO of the Irish Refugee Council, whose organisation has filed judicial reviews on behalf of two asylum seekers who have been left without housing, said the state presented “a long affidavit” to the judge on 12 May.

A barrister for the state said that the situation for homeless asylum seekers had improved, said Henderson, because new beds were becoming available.

Things had gotten better in terms of access to a daily expense allowance and support services, they had said.

Not everything they said necessarily reflects reality, though, Henderson says. “And ultimately, we still have 475 people on the streets,” he said on a phone call on Monday. The judge accepted the affidavit and adjourned the case until 24 May.

But the fire at the makeshift shelter on Sandwith Street on Friday and the events on Saturday – when a group of anti-immigrant protestors seem to have got the go-ahead to march past homeless asylum seekers outside the IPO offices – clashes with the state’s argument that the situation had improved, says Henderson.

“What was said in the affidavit is in stark contrast with what happened on Friday and Saturday,” he said.

A video from the march on Saturday, shows a group of men and women marching past asylum seekers’ tents carrying tricolours. One woman can be heard repeatedly shouting: “Ireland for the Irish”.

Another woman with short pink hair and a megaphone says: “You’re not welcome, get out.”

At one point, a young man flings his lit cigarette towards asylum seekers.

Gardaí can be seen walking in front of the crowd too.

The recent judgment in favour of the young Afghan asylum seeker mentions how his case is one of many brought by those entitled to “material reception conditions” under European law.

That “material reception conditions” means access to housing, food, clothing in kind or as financial allowances. Plaintiffs in these cases are young lone asylum-seeking men, it says.

But not all homeless asylum-seekers can access legal representation to bring cases to court.

The Legal Aid Board doesn’t pay lawyers to file judicial review applications at the High Court on their behalf.

Some lawyers work for asylum support non-profits and can take some cases to the High Court free of charge. Some may do it out of legal interest, and some out of kindness.

In the recent court case, for example, a youth worker at the Irish Refugee Council had filed a judicial review on behalf of the young asylum-seeker.

The Irish Refugee Council has its own legal department too.

Tienti, the asylum-seeker who lost his accommodation after complaining about missing clothes, says he asked his legal aid solicitor if they could focus on his need for re-accommodation and fight for that on his behalf.

“My request was to ask her about my re-accommodation, some sort of solution to this,” he said on Saturday.

But his lawyer just passed on the details of a private solicitor who’d charge him for representation, he says. “She said she’s private, and she would charge you like a €1,000 or something.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.