What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

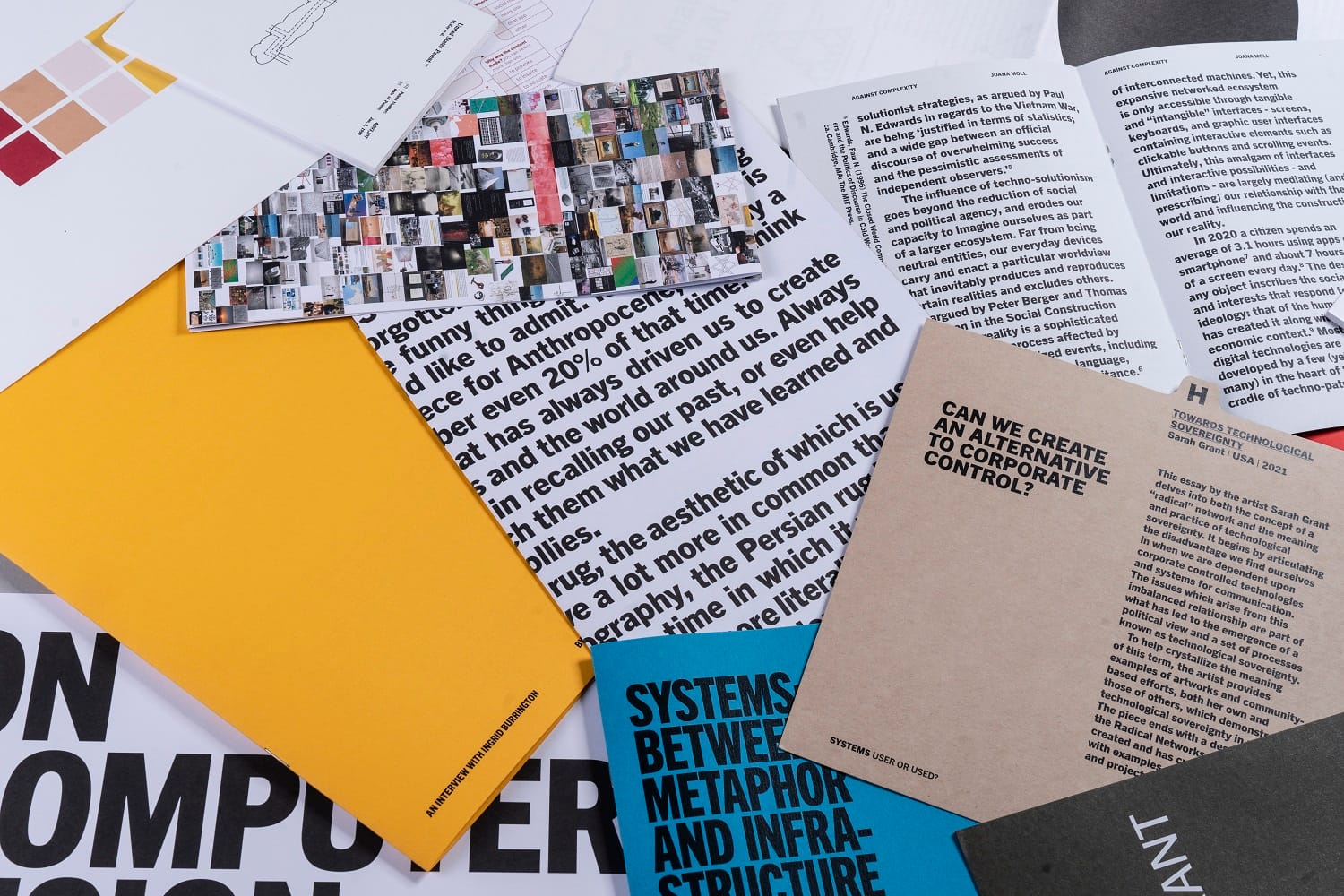

Presented in a red folder, SYSTEMS is a rummage of artworks, essays, maps, interviews, and toolkits that interrogates the often invisible systems that shape our everyday life.

Many exhibitions moved online during the pandemic.

“We said let’s do the opposite of that,” says Mitzi D’Alton, one of the producers behind the Science Gallery’s SYSTEMS exhibition.

They opted for paper.

Presented in a red folder, SYSTEMS is a limited-edition exhibition, a rummage of artworks, essays, maps, interviews, and toolkits that interrogates the often invisible systems that shape our everyday life.

Those include the networked system of the internet, the breakdown of Earth’s ecosystems, and the bureaucratic system of asylum.

It’s about offering unusual avenues to explore those systems working away around us, whether digital or analogue, says D’Alton. “That are both positive and negative.”

A big focus is on the digital, and a critique of the system perhaps we engage with most continuously – the internet. What is it? Where is it? How does it work? How can we garner more control over it?

“In the past two decades the internet is the thing we’ve all become completely integrated within,” says Paul O’Neill, co-curator and lead researcher of the exhibit, yet it’s something that is incredibly hard to explain.

People understand likes, emojis, how to binge on Netflix, he says. “But underneath that surface, that sort of interface, we don’t really have a command where all this stuff is.”

Open the folder and the eighteen art works inside are separated by coloured tabs. Each tab gives the title, the artist’s name, and a brief synopsis of the work.

“It’s kind of like a Christmas stocking in that there’s so many different pieces in it,” says Rory McCormick, who designed it.

The works reveal themselves differently as they unfold. They’re printed on different paper.

“We tried to make everything different so that they’d all have their own voice,” says McCormick.

The folder itself is like a secret dossier, which is apt for an exhibition dealing with the invisible systems that govern our daily life.

Paper, says O’Neill, is an appropriate form for an exhibition that takes a highly critical stance towards the increasing dominance of the internet in our lives.

“One of the themes in SYSTEMS is we don’t always need a digital solution. There are other ways,” he says.

Many of the artworks share a concern with relying heavily on technology to solve the complex societal and environmental problems that face humanity.

In “ASUNDER”, the artists Tega Brain, Julian Oliver and Bengt Sjölén discuss a fictional supercomputer of the same name, employed to solve the world’s climate and ecological crises by generating geoengineered interventions in the Earth’s natural environmental processes in order to solve climatic issues such as flooding.

The work, according to the artists’ statement, aims to question our assumptions around computational neutrality and the inputs that go into building artificial intelligences.

For “Anatomy of an AI System”, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler made a detailed map that charts the making of an algorithm from the materials that meld into its hardware, that originate beneath the earth’s surface and journey from mines through factories and into the internet infrastructures that make machine-learning possible. An essay acts like the map’s key.

Vukašin Nedeljkovi?’s “Asylum Archive” is a series of postcards from life inside Ireland’s direct provision system for asylum seekers, as well as Tactical Tech’s Data Detox toolkit, a handy guide for taking control of your life online.

Understanding the nature of the internet is one of the exhibit’s chief concerns.

The internet is hard to explain, says O’Neill. “There’s this idea that the internet is an immaterial thing but, as discovered by a lot of the artists in the project, really it’s not.”

Within the red folder, Mario Santamaría’s “Cloudplexity” consists of a jotting pad of different representations of the internet, made in US patent applications.

All are variations of a squiggly cloud, occasionally labelled as “internet” or “network” in the centre.

Of course the internet doesn’t look like that, says O’Neill. It exists in physical places and that has consequences, he says.

“These network systems require energy and they are hugely extractive. They eat up the Earth basically both the raw material and the energy to run them,” he says, pointing to the current debate around data centres and energy use in Ireland.

O’Neill’s own practice involves giving walking tours of the physical infrastructure of the internet in Dublin. His contribution to the exhibition is an extension of his walking tours.

He has created a counter-map of Dublin, a type of map that complicates the conventional depictions of a place, to show the route of the T50 cable, a fiber-optic cable that runs along the route of Dublin’s M50, which passes through the data centres of the tech platforms along its way.

The map, illustrated by Ann Kiernan, is an attempt to show, in an abstract form, “the different corporate, digital and physical layers of the Internet within the city”, according to the essay that accompanies it.

It emphasises the materiality of the internet – the pipes, servers, data centers and labour that go into making it possible – and the political and economic decisions that come from the technology companies that base themselves here, the essay says.

Concerns around digital manipulation also informed the curatorial vision, says O’Neill. In particular, how the erosion of democracy takes place through real-life infrastructure.

“We wanted to hammer home the point that [while] all this digital manipulation happens online, there are physical, material processes that it’s happening on,” he says. “These exist in physical places, in countries.”

For the curatorial team, it was also important to shine a light on systems of inclusion, diversity and empowerment rather than just offer a critique of systems of exploitation and exclusion, says O’Neill.

D’Alton, the show’s producer, points to the work of SYSTEMS curator Sarah Grant as an example of a practice that strives to give people back agency over communications infrastructure.

Grant has run workshops through her own practice at the Radical Networks Arts Festival and conference which she founded, to encourage communities, especially marginalised ones, to practice a bottom-up technological sovereignty. In other words, communities can build and regulate their own communications infrastructure.

Says D’Alton: “It’s about affecting the system and creating your own.”

In her essay, Grant points out possible examples of technological sovereignty, such as secure drop boxes for journalists, or websites that document times community members are targeted by the police.

Grant’s work is about demystifying the telecommunications networks we use everyday and the processes that make them work, says O’Neill. “You’re kind of learning by doing and that in itself is empowerment and that in itself is a form of inclusion.”

By doing this there’s a potential to include larger groups of people outside of the Silicon Valley milieu in making decisions about how these communication systems operate, he says.

There are a limited number of copies of SYSTEMS: USER OR USED still at The Library Project at Temple Bar or online. You can also pick up a copy at The Fumbally Cafe this Friday, as part of “Correcting The Lasagne”.

[CORRECTIONS: This article was updated at 11.30am on 11 August to correct the names of two of the exhibitions and include the name of an artist for another. Sincere apologies for the errors.]

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.