What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

It’s part of a wider projected called “What Does He Need?” which is trying to create a public conversation about the current state of masculinity.

When Dylan Farrell was thinking about the lessons someone should teach a young boy growing up in the Dolphin House flats, there was one line that stuck in his mind.

“Get stick, give stick. That means you have to stand up for yourself nobody is going to stick up for yourself but you,” says Farrell, who lives in the flats.

Part of Rialto Youth Project’s Young Men’s Group, Farrell was one of the 16- to 18-year-olds who helped create the character Stevie, and the animated poem about him, which has the same name.

It was part of a project, led by artist Fiona Whelan and Rialto Youth Project, designed to understand the everyday lives and inequalities facing young men from oppressed communities in Dublin.

“The world is not fair,” says Whelan. “As an artist I feel just as much responsibility as anyone else to respond to that inequality.”

As the boy Stevie grows up, he ends up hustling crayons in the flats for money, and later drugs. “That’s not a good life to be living. That’s what I take away from the poem,” says Farrell.

For Whelan and Rialto Youth Project, creating Stevie with these young men was part of a larger project called What Does He Need?, which is trying to create a public conversation about the current state of masculinity.

For the first session with the Rialto Youth Project’s Young Men’s Group, Whelan arrived armed with a blank cardboard cut-out shaped like a small boy.

Straight away, the diminutive silhouette sparked curiosity.

He had no name and no discernable features. “I say, ‘I don’t know what his name is or anything about him,’” says Whelan, on Zoom.

The premise was for the young men to take responsibility for the boy, she says, and guide him through life in the flats.

At first Farrell and his friends were just messing, he says. “We didn’t think it was gonna become as big as what it was. We were only sitting around the table having a laugh.”

But, over time, they imagined Stevie into existence in the portacabins on the grounds of Dolphin House flats, the largest remaining council-flat complex in the state.

Each Monday, the young men, youth workers, and Whelan would meet there.

In the steel-clad cabins, they would chat, eat, play pool, and drink tea, all under the supervision of local youth workers Micheal Byrne and Thomas Dolan.

Each week, Whelan wrote the boys’ responses as a poem and brought it back to them. They discarded some parts and moved around others, until the boys felt like it was theirs.

At the same time, she says, “the youth workers are minding the process making sure it’s making sense for them”.

Stevie, the main character the young men created over roughly 10 weeks, carries visual hallmarks of poverty. He has “jet black hair and green eyes/ A few bruises on his arm” and his clothes don’t fit.

At four years of age, he’s neglected and depressed. He’s afraid of the police and the local bully who pulls his socks through the holes in his runners.

“Still too young to be slinging dope/ He hasn’t been given an ounce of green/ Or had score bags put in his pocket,” the poem reads.

He dreams of being a bodybuilder, a vigilante, or opening his own library.

A key objective of the project was to understand how men and boys are shaped by and influenced by the place they live, says Byrne, the youth worker.

“This is them being able to share their understanding of the community they grew up in and the value of witnessing things in that community,” he says.

“It’s the natural reality of what’s happening in those communities and hearing that from young people is actually really empowering,” he says.

“This wouldn’t have been a topical conversation they would have as a group of mates standing on the street corner in Dolphin House,” says Byrne.

To get a visualisation of what a young boy from Dolphin House flats looks like from them was interesting, he says. “Straight away they went to the wife beater and the tracksuit bottoms.”

Whelan says most of the magic happened from just sitting with the boys with pens and paper.

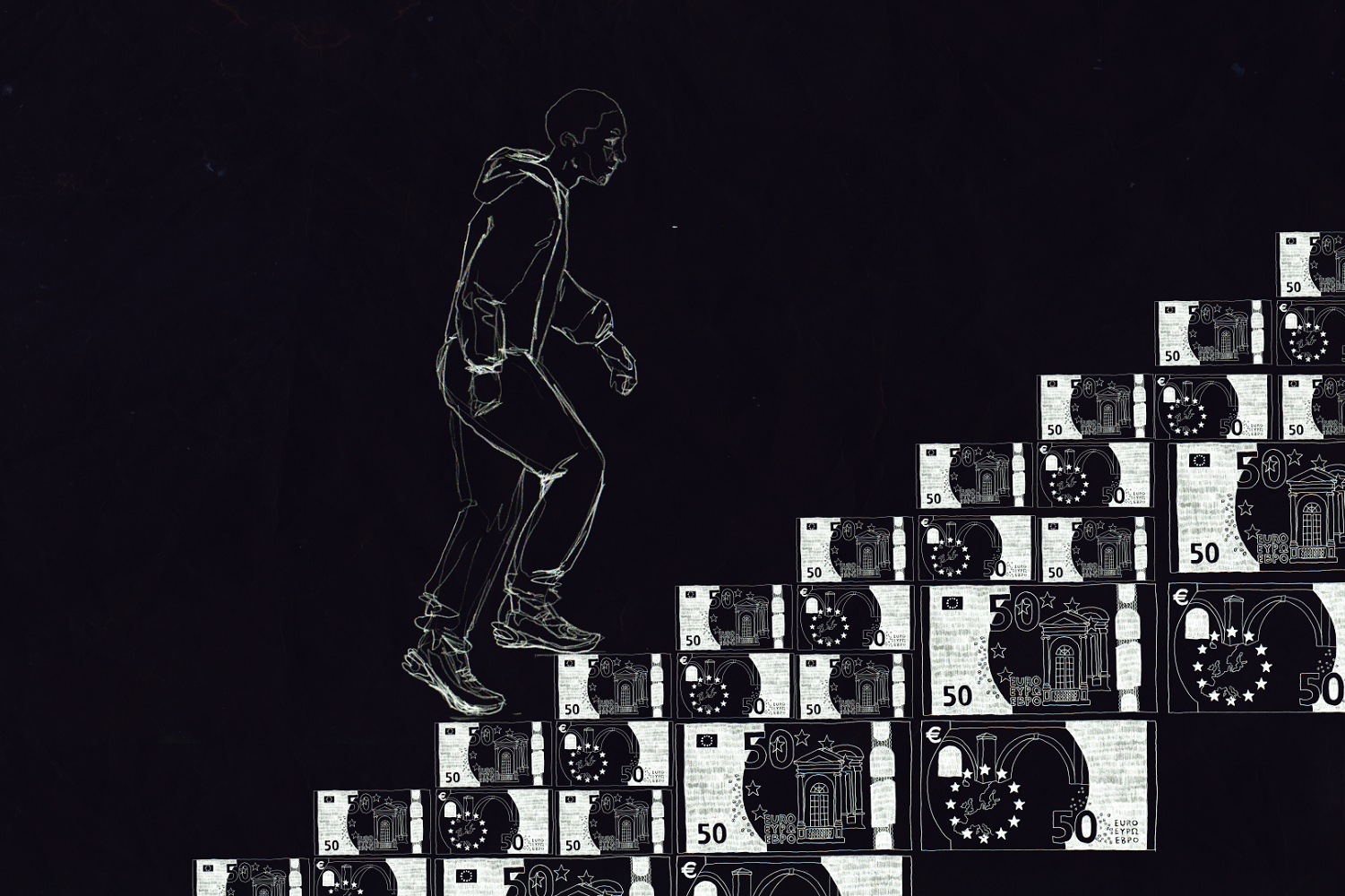

A poignant image in the animated poem – directed by Whelan with the visuals by Paper Panther Productions – shows Stevie at 14, selling crayons. A large Nike logo appears.

“Not poor now,” the sentence underneath reads.

It’s a crucial moment in the poem, showing the development of Stevie’s tough-guy persona and decisions that eventually steer him into drug dealing.

That “not poor now” moment came from one of the sessions, says Whelan, the artist. It’s what one of the young men said, as they added the Nike symbol to a drawing of Stevie.

Stevie the character isn’t real, but he is familiar to some of the boys, says Farrell, one of the boys who helped create him. “That’s a reflection of us.”

Some of them at least, he says. “Others in the group didn’t really grow up the way we would have so it was a mix in the group.”

Those involved in the What Does He Need? project have so far created 13 boys, including Stevie. There are also characters such as Cali, Luke and Conor-George.

The project has spread into other parts of the city too, like Stoneybatter, where the North West Inner City Network made up a character too.

Aside from creating these characters, Whelan, Rialto Youth Project, and Brokentalkers theatre company – who are collaborators on this wider project — organised an exhibition hosted by The LAB Gallery on Foley Street in Dublin 1, running from December last year to January 2021.

Statements such as “A strong male role model” , “A decent pair of runners”, and “Money, power and a bigger dog”, which came out of workshops on the needs of men, appeared on the windows of the gallery.

They’ve also set up a philosophy-with-men group exploring the concept of masculinity.

The idea for What Does He Need? grew from an earlier project Whelan and Rialto Youth Project ran called The Natural History of Hope, about women’s equality in Rialto.

Women in that project kept talking about “men as a liability in women’s lives”, says Dannielle McKenna, a project leader at Rialto Youth Project.

“For some women, the men in their lives are hurting them and they’re hurting themselves and each other,” she says.

What Does He Need? is a way to examine toxic masculinity, she says. But “you’re not looking at the behaviour as such but the need behind the behaviour that makes something happen”.

Patriarchy affects men as much as it affects women, says McKenna, “because it puts this expectation that men have to be this masculine person who is strong. Why are we doing that? We construct and decide what masculinity is.”

McKenna says they are now inviting those who have seen the animation – which is mostly people in Rialto for now – to write letters to Stevie. Forty-eight have so far.

The young men’s group has had its need to be heard met and now it’s time for the world to reply, says McKenna.

The group is also prepping for a temporary community-based school called School of Stevie to run this July, which will house the poem, animation and letters. Depending on Covid restrictions, it’ll be online, outdoors, or inside.

It could become a resource for other community groups to use to unpack themes with younger people, adults and teachers, says Whelan.

McKenna said a team member had suggested politicians visit the school “because they are the ones that need to be educated, they’re the ones creating the inequalities so you’re fighting a lot with the system.”

Farrell says that the turn that Stevie — the character he helped create — takes, drawn into drug-dealing for the money, isn’t a path he agrees with.

But he enjoyed the project and the process of discovery, he says, and would love to do something similar again.

Byrne, the youth worker, wants to create more projects like this involving young men. “There’s richness to a space like this. I want to get more men to engage with this richness.”

He says: “This is something that hasn’t necessarily been talked about, you know what I mean? Hearing young men talking about this is very inspirational and there’s pride in that.”

There have been two screenings of Stevie so far, one just for the community of Rialto and another open to a wider audience of youth workers, academics and activists on Zoom, which attracted almost 300 people.

People have been saying they didn’t know about the Stevies of the world, says McKenna. “Part of it is that the world needs to understand what’s going on for young men and particularly young men who are at risk and have a lot going on.”

“People really want it to have an ending, they want Stevie to be okay,” she says, “but it’s an unfinished story.”

[CORRECTION: This article was updated on 8 April 2021 at 4pm to make it clear that this project is a partnership between Rialto Youth Project and Fiona Whelan, working together. Apologies for the lack of clarity.]

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.