What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Francis Ducie has been modelling for artists across Dublin since 2007. “He’s kind of famous in his own way,” says Alan Clarke, an artist who teaches at NCAD

The life model pulls a chair to the back of the corner podium, clearing the space in front.

“We’ll do a combination of maybe standing and seated poses,” says teacher Louise Boughton, from across the big space.

Holding for 10 minutes to start, she says. “So this is the first one.”

The man plants his feet wide apart. He places his hands on his head, with his elbows akimbo, and lifts his brows to rumple his forehead, and lowers his eyes to stare as if lost a few metres in front, fixing on a single spot on the scuffed classroom floor.

“I don’t want to put off people by eyeballing them,” he says later. “Especially if you’re undressed.”

For this session, though, he is clothed. His dark grey jumper, collared with a line of buttons, hangs big on his skinny figure.

Seven students, sat at easels, are shuffled around him in a half-moon of chairs and with the pose set, they choose their tools.

One picks up a 2B graphite pencil, another an oil pastel, others sticks of charcoal, thick markers, and all start to sketch interpretations of the oft-interpreted face and figure of Francis Ducie.

On this Thursday, it’s Ballyfermot College of Further Education (BFCE).

Other days, Ducie’s body might take him to the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), to the National College of Art and Design (NCAD), or to the studios of Block T.

Ducie’s first booking as a life model was in 2007. He was sitting nude for the first time in a room of eight artists at the United Arts Club on Fitzwilliam Street Upper, he says. “All around in a circle and they all looked at me.”

The guy who had booked him thought he would freak and run, Ducie says. But he didn’t.

He next sat for students at the Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology. If he had to talk, he should move only his mouth, he says he learnt that time. “Your man more or less said you’re supposed to stay still.”

“I’m a better model now than I was then,” said Ducie recently. “Because I know what I’m doing.”

Ducie is booked all over now, because he is professional, says Alan Clarke, an artist who teaches at NCAD.

“He’s kind of famous in his own way,” says Clarke.

“He’s reliable,” he says.

“Really accommodating as well,” says Boughton, the teacher at BCFE.

“And he’s actually quite good at putting people at their ease,” says Clarke, which is no mean feat given, at times, the unusual arrangement of a hushed room with a naked person slap bang in the middle.

But there’s much more to it than that.

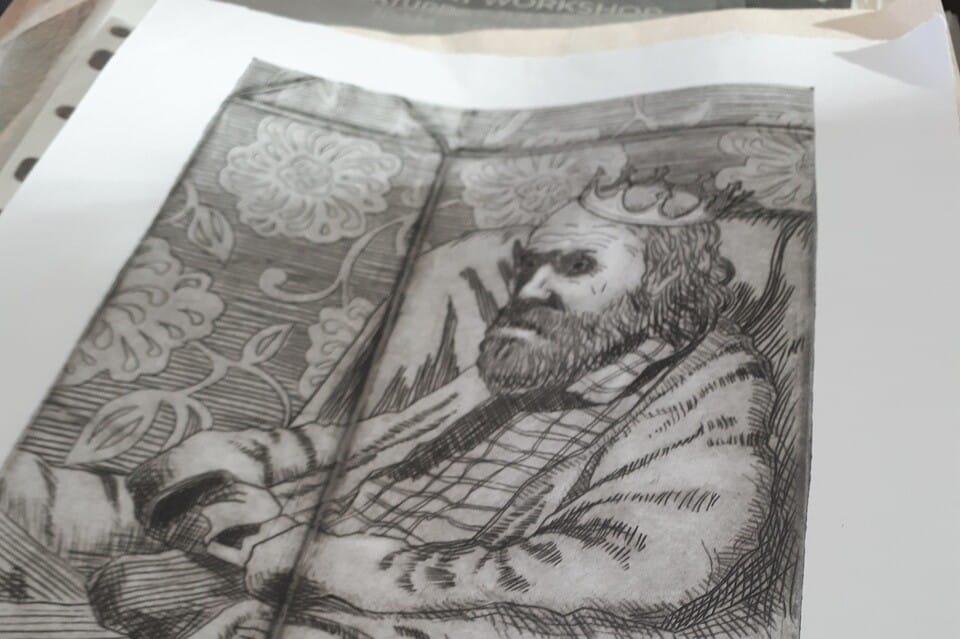

He makes a brilliant subject, says Clarke, it’s the look that he has. “Of having just stepped out of the Bible, or stepped out of Lord of the Rings.”

“I always think of St Jerome in the Desert,” says Yvonne Pettitt, an artist who has done classes at the RHA.

He is lean so you can see his muscles and form, says Brian Gallagher, who runs the life drawing at the United Arts Club.

Ducie’s face is distinguished, all angles and planes, he says. “He’s like a gem to draw, you know.”

“They were always trying to fit me in a box,” says Ducie of his early years at school in Blackrock, “and I never felt like I fit it in at all.”

He was bullied, called a waste of space, and mocked by teachers, he says. It scarred him, says Ducie. “I believed it.”

Once out of school, he had drabs of work experience. Stock control, packing flyers, nothing lasted long, he says. “None of them ever were going to lead to anything.”

In his 40s, Ducie found his way to an organisation for people with Asperger’s. He’s never been officially diagnosed, he says. But the group supported him.

They got him a part-time job at the supermarket Iceland, he says. At first sorting recycling, later on the shop floor.

He remembers the first time a manager made him responsible for setting an alarm. He didn’t think he could handle that, he says. “I was always afraid of making a mistake. I was afraid to try things.”

But his boss spoke well of him, he says, and it changed his world. “It really built up my confidence.”

“For 20 minutes, Francis,” says Boughton, from the edge of the classroom.

“Is that alright?” he says, leaning into a new position, sitting against the chair, his right hand tucked behind his back, his frame twisted and ankles crossed.

“Once it’s comfortable,” she says.

Around him, the students work to meet their brief, to emulate the style and techniques of chosen artists they admire.

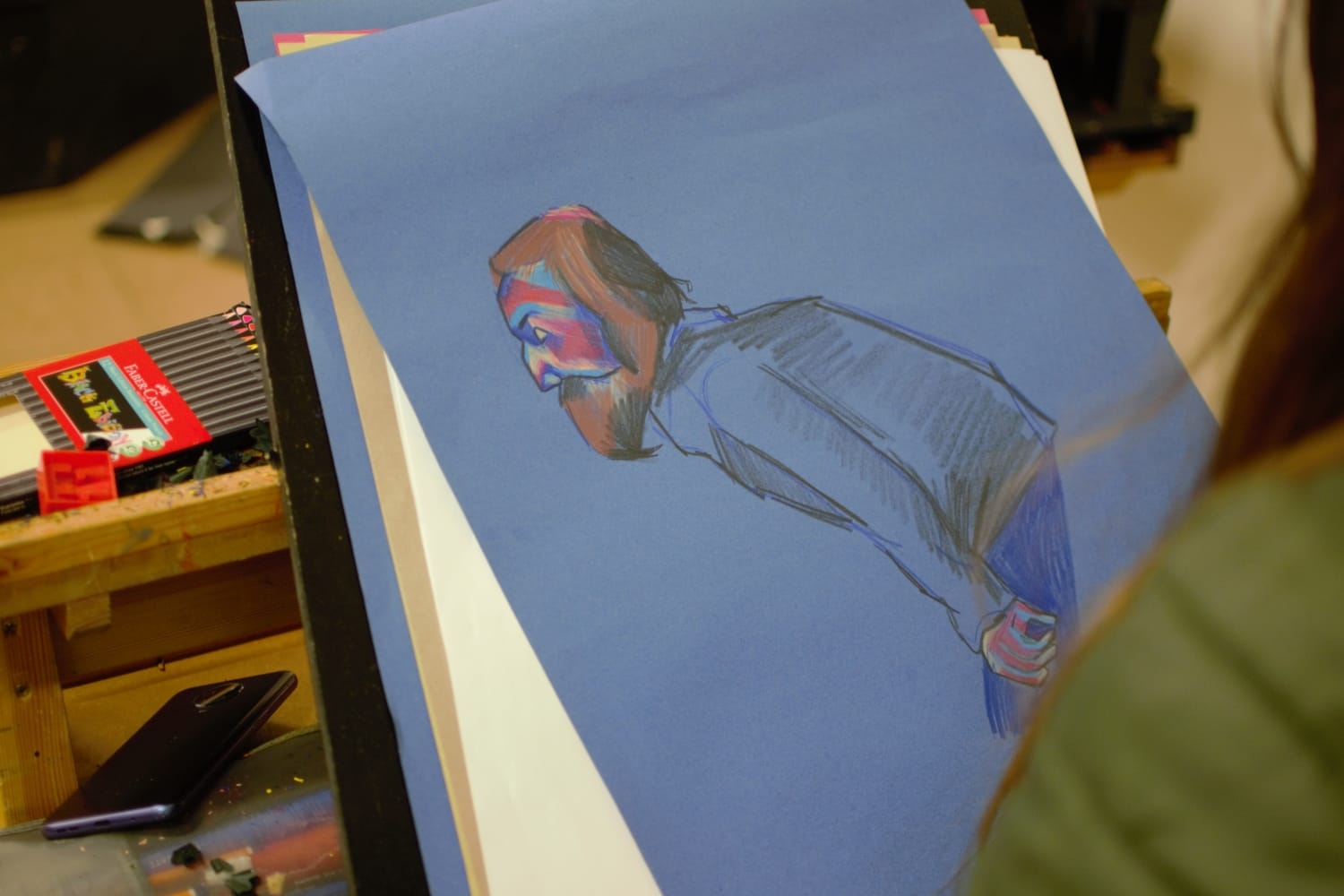

At one end of the row, Ruby Thomas fills in the crook of a nose. She blocks out colours, bright reds and blues, heavy lines and sharp angles, as she mimics the ruddy works of Sonia Delaunay.

Jake Conroy leans in to his paper. He darkens the wrinkles on his Ducie’s forehead, streaks in wisps of hair, as he searches for the touch of pre-Raphaelite Artemisia Gentileschi.

“You can spend a whole day on a portrait,” says Ducie, not breaking his pose.

“I’m sure you’ve sat for a day or two days even,” says Boughton. He’s sat, she tells the class, for most of the biggest artists.

There are hundreds of images of Instagram, Ducie says, joining in. There are paintings, sketches, and sculptures, and even appearances on the big screen.

He was an extra on Vikings, a man spaced out on mushrooms lying on the ground, says Ducie, and in the film, The Green Knight too – a sharecropper’s husband that time. “I was treated like royalty, I had my own portacabin and all.”

Laura Maleady dabs blue paint on her canvas, surrounding her Ducie in a triangular frame, as she mimics the Art Deco elegance of the artist Erté.

Treated like royalty, says Ducie again from the podium. “A taxi picked me up from my apartment.” His nephew watched the film but didn’t spot him, he says.

Jessica Leonard chuckles as she works, building up her picture in confident marker strokes. “Get on to your agent and tell him it’s not good enough,” she says.

Ducie had body issues when he was younger, he says. “I would have been afraid to take my shirt off, I would have been worried about what people think.”

“I have a bit of a pigeon chest,” he says.

When he was 38, he says, he drifted down to a Dalkey swimming spot, one favoured by naturists, on the craggy coastline off Vico Road. He’s not sure what drew him there, he says.

“I liked swimming as a kid,” he says. His dad would take him to Killiney Beach, and there had been a pool at the junior school at Blackrock College where he went for a while.

At Vico Road, one of the ladies was kind, he says, encouraging him to try out nude swimming. “Gentle Jesus,” was what she called him, he says.

Ducie goes most days now, he says. “It’s an escape from everywhere.”

A friend at the swimming spot suggested he take up modelling, remarking at how comfortable he seemed with himself, says Ducie.

His body, nudity, it just doesn’t matter to him now, he says. “What’s the big deal?”

The best thing he ever did was start swimming, he says. “People accept you.”

Just like the art world and modelling, he says. “People accept me how I am.”

It doesn’t matter that you’re not perfect, he says. Nobody is.

“If you’re looking for perfection or you’re looking to be perfect,” says Ducie, “your head’s going to be seriously messed up.”

About an hour into the session, Boughton called a break and the students filed out of the room. Ducie stepped off from the podium and circled around to the front of the easels.

He took out his phone, and leant back to take a photo. “Oh that’s really nice,” he said, of the work by Hannah Tynan in the luminous style of Joaquín Sorolla.

“He’s probably going for some kind of character there,” he says, as he passes another. “It’s kind of different.”

“That’s going somewhere else,” he says, of a third.

Most drawings and sketches of Ducie are done for practice. Life drawings are a funny business, says Clarke, the artist who teaches at NCAD. “People just don’t tend to buy them.”

People mostly buy art for their walls, he says. They’re squeamish about putting up images of naked men – as most life drawings are.

Clarke has sketches of Ducie lying all over, he says. “Lots of them are in my studio in a drawer, and a couple of them are framed.”

Busts aren’t big sellers either, unless people know the subject, says Clarke. But he has sold one of Ducie, he says. “It was bought simply as a piece of art.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.