What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Nowadays a co-working space, the Academy at 42 Pearse Street was once a meeting place for women demanding the right to vote.

The building at 42 Pearse Street is a co-working space now, a part of Dublin’s 21st-century start-up scene.

It’s splashed with the brash, bold colours and geometric patterns of co-working company Huckletree’s branding. There are shared desks topped with computers, a kitchen, and a yoga and meditation room.

But among all this, you can still spot traces of this building’s 19th-century origins: high ceilings, bits of ornate plasterwork and, in some rooms, crystal chandeliers.

Way back then, this building, the Academy, played an important role in the women’s suffrage movement, and Dublin City Council historian-in-residence Maeve Casserly is trying to raise awareness about that side of its past.

This is all part of her efforts to tell people more about women’s role in the city’s history.

“In Dublin you see a lot of plaques above buildings, like the Oscar Wilde [House] in Merrion Square. But in general, there’s not that much for women,” she says.

Casserly has mapped out lesser-known sites that tie into the history of the women’s suffrage movement.

Last year, to mark the centenary of some women in Britain and Ireland winning the right to vote, she gave a walking tour of these sites in Rathmines and the city centre. She plans to give more of these tours in October.

Several prominent activists from the time lived in Rathmines. including Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Kathleen Lynn and Anna Haslam. It was also home to Countess Markievicz and Dora Maguire.

“A lot of them were neighbours,” Casserly says. “They had been involved in the whole suffrage movement since the 1860s.”

The suffrage movement in Ireland was initially about handing out petitions and attending meetings, Casserly says. “Then Hanna and her friends came in and started smashing windows.”

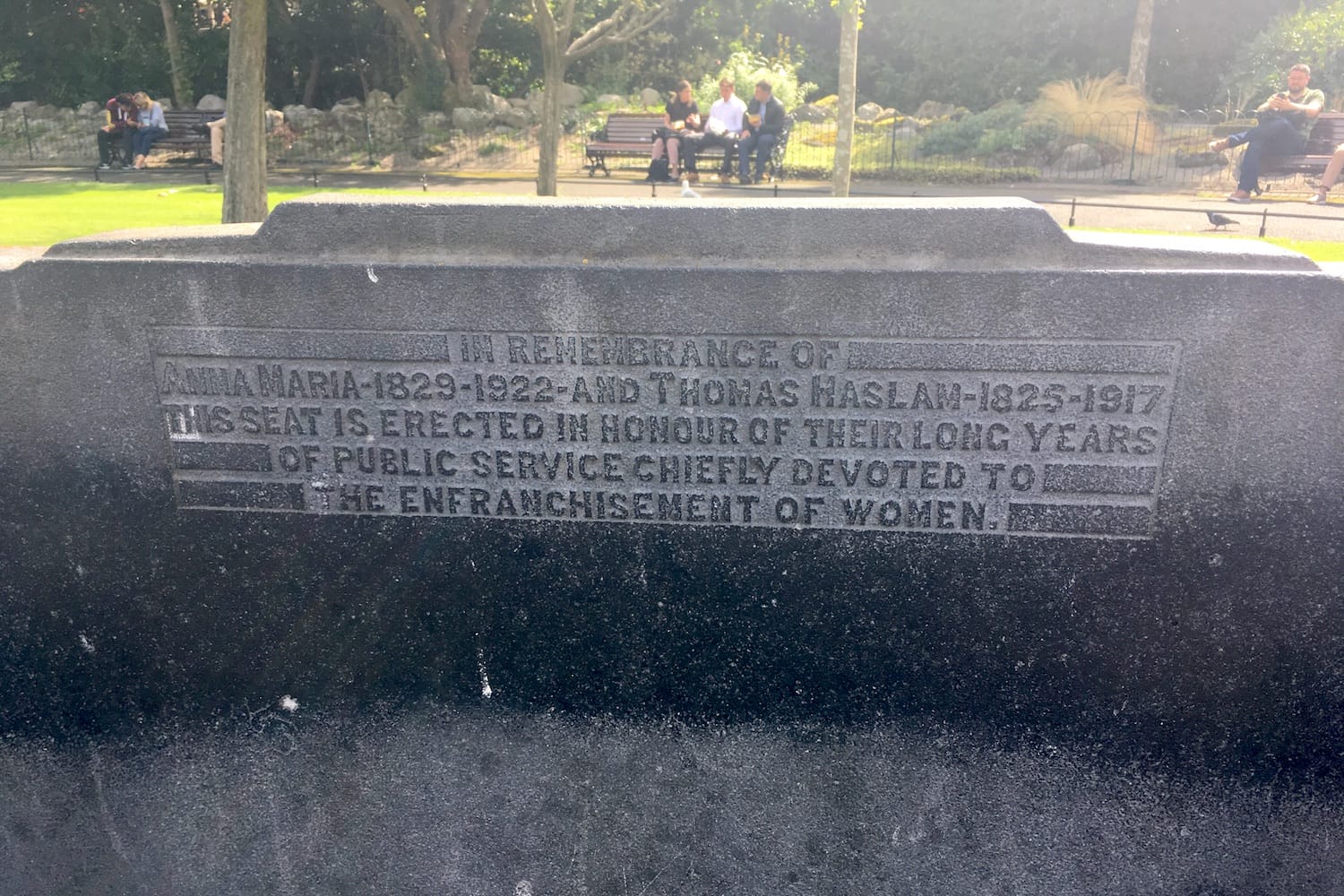

When Casserly runs her tours, she takes people to St Stephen’s Green to see the bust Constance Markievicz, and the bench dedicated to Anna and Thomas Haslam.

There’s a harder-to-find bench bearing a plaque for Louie Bennett and Helen Chenevix, members of the Irish Women Worker’s Union, too.

And there’s the Academy, which back then was known as the Antient Concert Rooms.

The building was designed by James Cook for the Dublin Oil Gas Company’s industrial headquarters in 1824. The company manufactured gas from fish oil, but went bankrupt in 1834 after the price of fish oil rose.

The building lay empty until was acquired in 1832 by the Society of Antient Concert Rooms, which promoted classical choral music. Renamed the Antient Concert Rooms, on 20 April 1843, it hosted its first concert.

“The building is still in an unfinished state […] but when completed, will not be inferior, for the purposes for which it was constructed, to any other in Europe,” according to the Dublin Evening Mail.

The article gave a favourable review of the evening’s music, describing the society’s performances of composer Handel’s Messiah as surpassing “the most sanguine expectations of all the lovers of harmony and melody who were present”.

The Antient Concert Rooms would go on to host the classes for the Royal Academy of Irish Music, performances by the Philharmonic Society and concerts by international singers and musicians.

The rooms are the setting for James Joyce’s story “A Mother” in Dubliners, about a greedy mother who holds up a concert, demanding her daughter be paid in full before the final show. They get a mention by Leopold Bloom in Ulysses, too.

The Antient Society disbanded in 1864 but the Philharmonic Society continued to use the rooms. Soon, so would women demanding the right to vote.

In 1876, the Haslams founded the Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association.

“In the first years of the [association], the major resources of the committee were expended on large public meetings to which prominent speakers were invited,” according to Carmel Quinlan’s PhD thesis and, later, book on the Haslams.

The first meeting that the fledgeling association arranged was in the Antient Concert Rooms on 6 April 1877.

While this one faced the “determined hostility of a small knot of disturbers”, according to Quinlan, Casserly says meetings were generally able to go ahead without much difficulty.

Another group fighting for women’s right to vote was the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL), led by Sheehy Skeffington and Margaret Cousins.

Before establishing offices of its own on Westmoreland Street. the IWFL rented rooms from the Labour Party in the Antient Concert Rooms.

They called themselves suffragettes, instead of suffragists, Casserly says. “They would have argued that they needed to take a more radical stance,” she says.

It was at the concert room’s buildings that they would plan actions like the 1911 census protest.

On 1 April 1911, a policeman burst in during one of their meetings and demanded to know if the IWFL planned on refusing to fill out the 1911 census, a tactic also used by suffragettes in Britain.

Women like Halsam, Bennett and Sheehy Skeffington did not return census forms, but the enumerator who stopped by Sheehy Skeffington’s home was adamant he fill in her details, though incorrectly.

“[I]n general, my impression has been that a lot of the women who organised these meetings or rallies were middle-class. It’s been hard to get [records] on working-class women’s meetings,” Casserly says.

But the Antient Concert Rooms was also where the Irish Women Workers’ Union (IWWU) was also founded, on 5 September 1911.

It aimed to improve conditions for workers, particularly women in the Magdalene Laundries. Key figures would include Bennett, Chenevix and Rosie Hackett.

At the founding meeting, Markievicz said the IWWU would not only give women a greater voice in the workplace, but would help the suffrage movement.

Today, the foyer of the Academy has been turned into a museum of sorts, with quotes from Joyce’s books, information about the history of the building, and old photos.

But, somehow, there’s little mention of the role it played for the various women’s groups.

Casserly says people who do her tour say they were not aware of the many landmarks connected to famous Irish women.

“A lot of the buildings the women would have used aren’t really remembered in that kind of way,” she says.

“There was [a plaque put up] on Ship Street last year for Hanna Sheehy Skeffington … but it’s only come up in the last little while – I think because of things like centenaries.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.