What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

They meet every Sunday in a different spot, where they quietly contemplate and capture the details that others usually overlook.

When the heavy rains cleared and the sky brightened, the sketchers came out.

Paul Naessens hunkered down among the vaults and granite angels of Mount Jerome Cemetery on Sunday afternoon, his back against a tall slab of rock, a tin of colouring pencils sit in front of him.

He held a dip pen and stippled small ink dots onto his sketch pad, later adding texture with a technique called cross-hatching. The outline looks like a bathtub on top of a tombstone.

Naessens hadn’t sketched in 35 years, he says. Two years ago he “went back to the drawing board”.

A few months ago, he joined the Dublin Sketchers, a group that meets every Sunday in a different corner of the city. They spread out and sketch, then meet up in a pub afterwards and show off their work, passing around their sketchbooks.

Dotted around the cemetery on this Sunday, there are others with sketch pads, contemplating the granite angels, faded inscriptions and other details that people might usually overlook.

Families and loners stroll into the cemetery. A flower seller sits on a chair, hood up, smoking a cigarette.

Marie-Hélène Brohan Delhaye, sat a few metres away, works on a landscape of tombstones and trees, in various shades of green.

The group was founded about 11 years ago, she says. Her sketchbook rests on a bit of cardboard, and she sprays her tin of watercolour paints, prepping them, as she talks.

Three friends – Sarah O’Reilly, James Moore and Jessica Peel-Yates – organised the first small meet-ups, says Brohan Delhaye.

They created a blog and email list and from there, it’s grown. There are about 50 regulars, says Brohan Delhaye, who joined three years ago.

Two years ago, the Dublin Sketchers affiliated with Urban Sketchers, a movement founded in 2007 in the US, with chapters in several cities around the world.

It didn’t change much day to day, she says. But “it’s a great network to have when you’re travelling”. In Japan last year, she got in touch with the group there.

“I went sketching for a whole morning with a girl in Kyoto, a girl I’d never met before,” she says. “After that morning, we were best friends.”

Every month, one core member gets to choose the weekly locations – which are advertised on social media.

“That’s why it’s been able to last for so long,” Brohan Delhaye says. “It’s not one person doing everything.”

They’ve gone nationwide, too – to Galway, Cork, and Kilkenny, she says. Next month they’ll hold a three-day event on the Aran Islands, with workshops, talks, and plenty of sketch-abouts.

Cemeteries are among the best places to draw, Naessens says. “It’s very atmospheric. There are lots of shapes, shadows. There’s nature.”

What Naessens is actually sketching is a sarcophagus, mounted on a stone pedestal. It’s a monument for Thomas Drummond, a well-known surveyor and under-secretary for Ireland in the late 1830s.

A cemetery is a place of great life, says Naessens. “These people all had vivid lives. It is a place of sadness but it’s not morose or morbid.”

Maggie Byrne would come to Mount Jerome most Christmas days with her family growing up, she says.

That gave her an extra nudge to come along with the sketchers for the first time on Sunday, she says, sitting in the shade of a tree, with a few pots of inks, and a small jar of water. “I thought, I have to go,” she says.

In black pencil, she has sketched the outline of the green tank across the path, drawing the small rivets.

It’s not just objects that they draw and paint. Often, sketchers sketch strangers too, says Brohan Delahaye, pointing to two watercolour portraits in her book.

“If you’re sitting at a café or in a park, you sketch people that are across from you,” she says. “It’s quite an honour to be sketched, I would think.”

“You spend time looking at the city carefully,” says Pat McAfee, later, at McGowan’s pub where the group has gathered at 4pm.

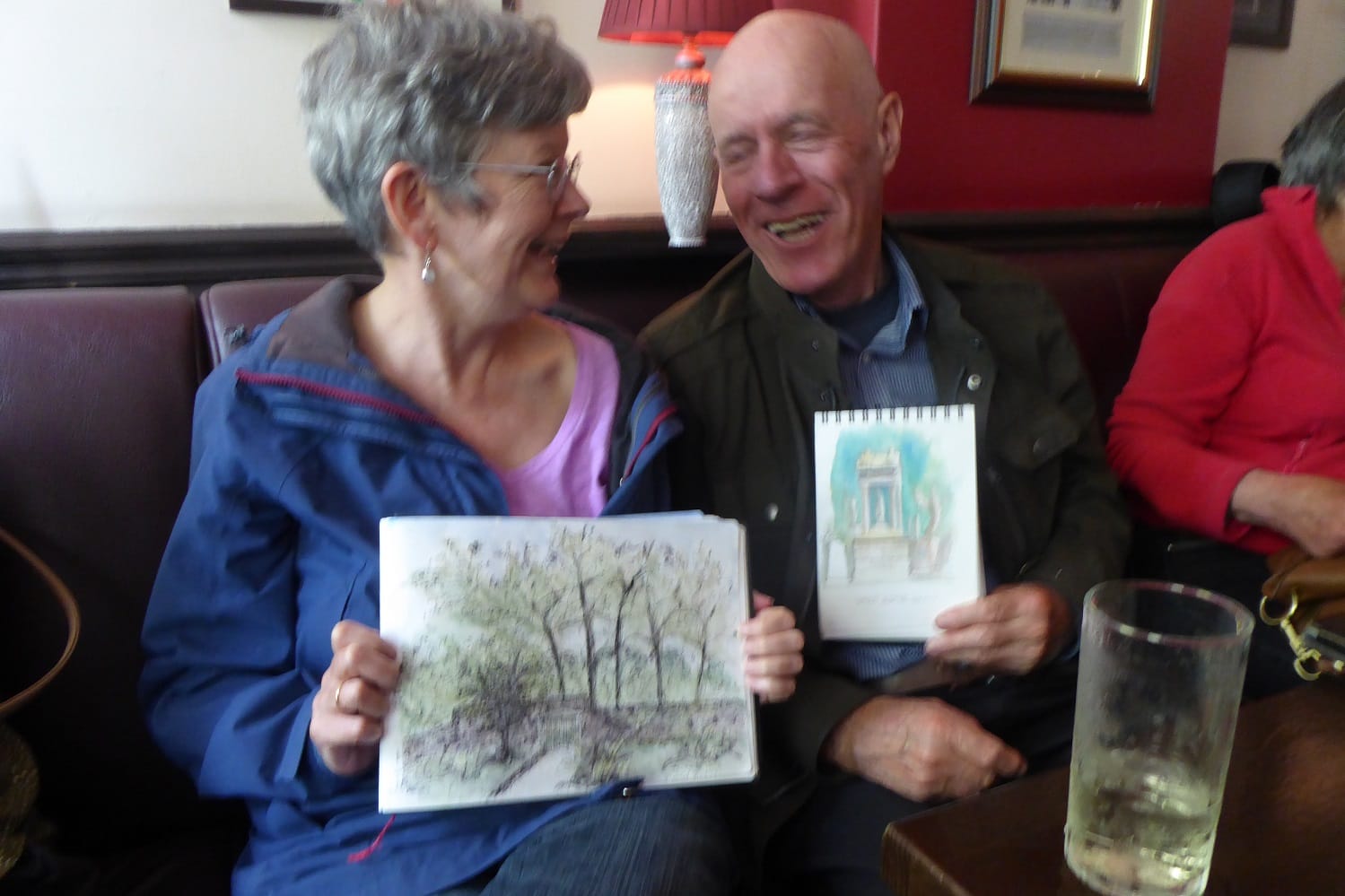

Sixteen people are tucked into a booth, passing notebooks around as they drink teas and coffees.

“It’s kind of meditative,” says McAfee. “You see little details because normally you might walk past it, but you sit and you look carefully.”

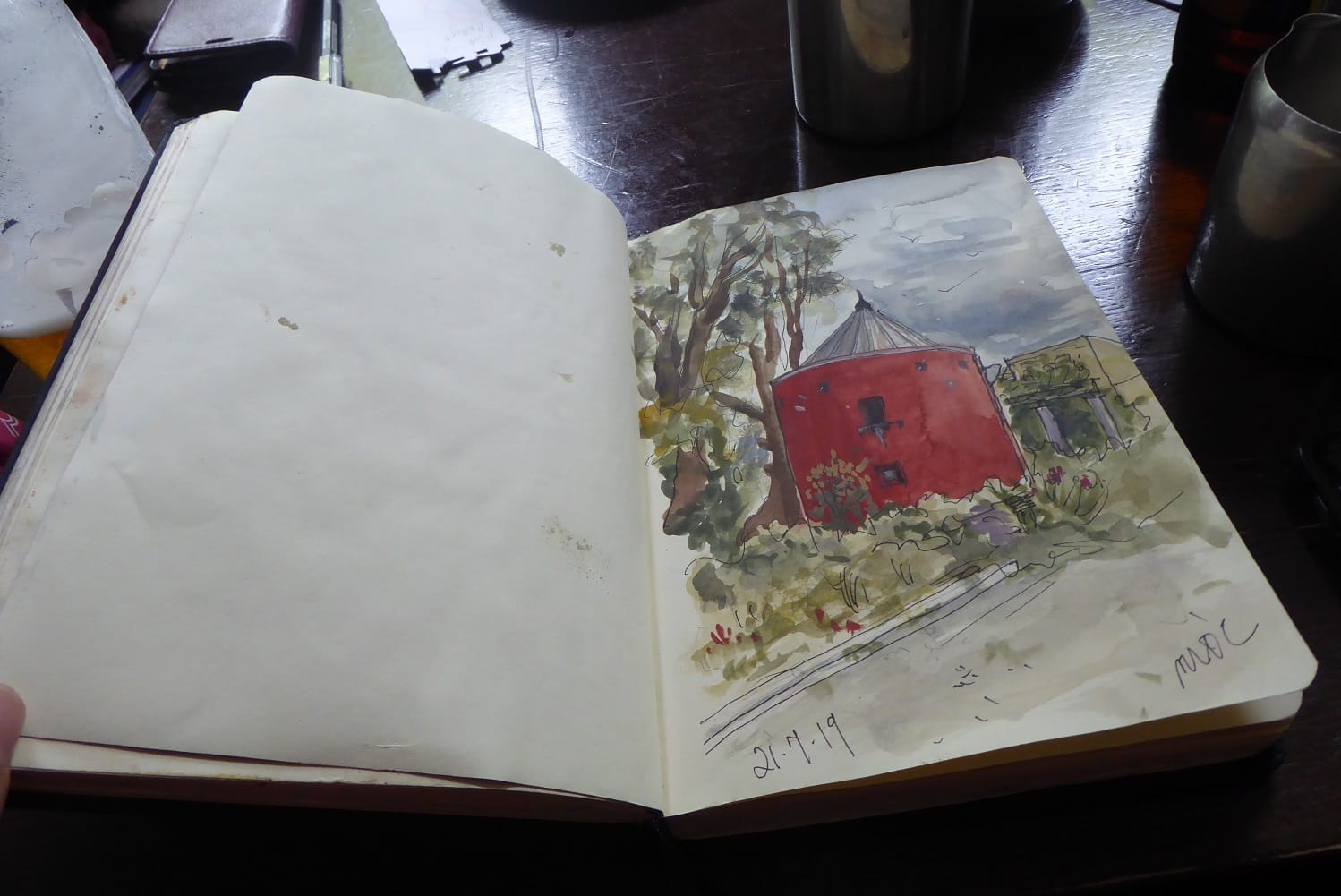

At one table, people marvel at Mary O’Carroll’s book, each page showing a recognisable but not-so-famous scene from the city.

“That’s called gouache paint,” Naessens says, of a rust-coloured sketch of the roofs of buildings behind the back of the old Central Bank.

Isoilde Dillon, an architect, says so much of her day job is done on computers now. “So it’s nice to get back to hand-drawing,” she says.

You can dip in and out of the group too, she says. “You don’t have to go every week. It’s very spontaneous.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.