Grand vision for Pigeon House on Poolbeg Peninsula is shrunk way down – for now

Council officials want to keep renting it for about the next five years to the wastewater plant operators.

Councillors have the responsibility to set the rate each year, so they should also get to decide how to spend the resulting income, finance committee chair says.

A big change to the local property tax system, which might have left Dublin City Council more to spend this year, didn’t.

While the central government ostensibly gave the council millions more with one hand, it took them right back away with the other.

In the end, the government decides how much the council gets to spend, and it’s about the same every year, no matter what, councillors say.

So maybe it’s time to do away with the annual exercise where councillors are asked to set the local property tax level, some councillors said at a meeting of their finance committee earlier this year.

“I think we should abolish that power,” Labour Councillor Alison Gilliland said at the meeting in March. “It’s an absolute waste of time.”

On the phone last week, Sinn Féin Councillor Séamas McGrattan, who chairs the committee, said he agreed. “I would be coming from the opposite side from Alison, but coming to the same conclusion.”

Either that or, if the government is going to continue to give the councillors the responsibility to set the local property tax rate each year, they should also get to decide how to spend additional income if they increase it, McGrattan says. Or make cuts if they decrease it, he says.

The government has been working through changes to funding for local authorities in the last couple of years. That has included new legislation amending the local property tax system in 2021.

Those changes are continuing now with a review by a national working group of an aspect of the local property tax system, known as “baseline funding”. It’s due to issue its report this month.

But those reforms are relatively superficial, councillors say, and do not address the fundamental lack of local control over the council’s ability to raise and spend money.

“If we increase the local property tax, or rates, we should then have the power to spend it,” McGrattan says. “That’s the heart of local democracy around the world.”

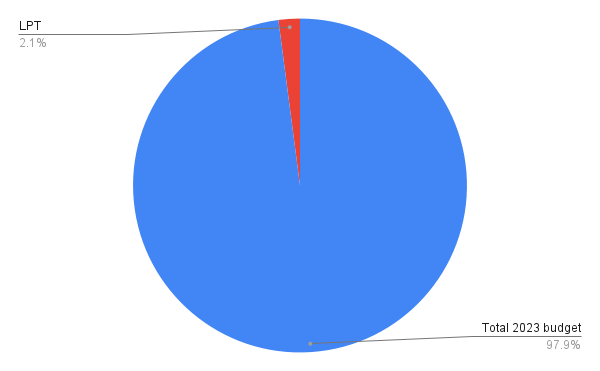

The first thing to know about the local property tax is that it only provides about 2.1 percent of the money Dublin City Council spends on day-to-day operations.

The council’s budget in 2023 is €1.24 billion.

The three main funding streams are government grants and subsidies (€442.4 million), commercial rates (€380.8 million), and “goods and services” like social-housing rents and parking charges (€349.1 million).

Only €26.2 million comes from local property tax. “The local property tax is a pittance,” says McGrattan, the chair of the finance committee.

It could be a bit more. There’s a base rate for the tax, but each year councillors are asked whether they’d like to vary it above or below that by 15 percent.

Each year for at least the last five, Dublin City Council has voted to keep it as low as they are allowed: 15 percent below the base.

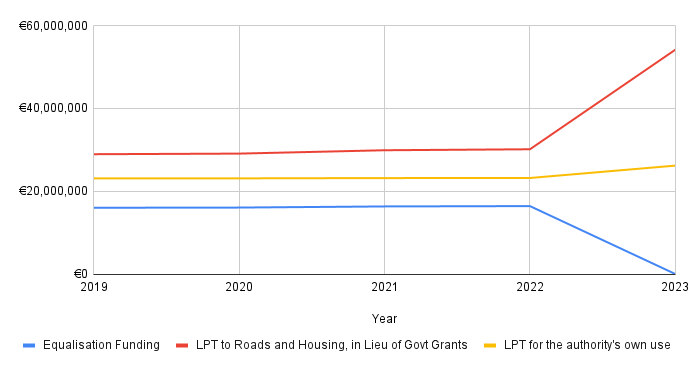

One of the arguments for that has been that raising it would mean sending more of Dubliners’ taxes out of Dublin to help fund rural councils – via “equalisation funding”.

The government sets a baseline amount of local property tax money it says councils will get each year. In 2022, 11 councils had more than the baseline, and 20 had less.

So the government took local property tax money from the ones doing well, and gave it to the ones who needed a bit more. That’s the equalisation funding.

Now, the government’s Programme for Government: Our Shared Future pledged that “All money collected locally will be retained within the county.”

And, indeed, the government did away with the equalisation funding system. The idea is that supposedly Dubliners’ taxes won’t go to, say, Roscommon County Council anymore.

Dublin City Council, both the administrative side, and the elected members, thought this would mean they’d have more money to work with.

“The equalization fund was removed and we thought we’d get around between €16 [million] and €20 million more. That didn’t happen,” said Kathy Quinn, head of finance for Dublin City Council, at that March finance committee meeting.

“We assumed we’d be getting that money from the equalisation fund,” said McGrattan, the chair of the finance committee.

Instead, the government directed that the council use more of its local property tax revenue to cover roads and housing costs, in lieu of getting government grants to cover those costs.

In the end, the council has only a relatively small bit more local property tax revenue to spend: €22.2 million in 2022, €26.2 million this year.

“Is there any incentive for us to bring in more local property tax?” Fine Gael Councillor Paddy McCartan said at the finance committee meeting. “The more we bring in, the more it’s offset, seemingly, by reduction in funding from central government.”

It doesn’t really matter if councillors vote to raise the local property tax rate, says McGrattan, the Sinn Féin councillor who chairs the finance committee.

Supposedly, the council would get to keep the additional money raised, but in practice the government would also then reduce other funding it gives the council – and in the end, the council would have the same amount of money to spend anyway, he says.

Part of this complicated local property tax equation is the “baseline” amount of local property tax revenue that the government says each council will get. There’s a different number for each different council.

If a council misses its number, it gets a top-up – previously from other councils via equalisation funding, now directly from the government. If it beats its number, the government says what to do with the “surplus”.

Dublin City Council’s baseline was about €19 million in 2017. It was about €19 million in 2023. In fact, baseline funding allocations for councils “are broadly unchanged since 2014”, a Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage spokesperson says.

Where did Dublin City Council’s number come from? Quinn, the council’s finance head, said she had no idea. “It is simply impossible to understand how that was calculated.”

Dublin City Council’s baseline is one of the higher ones, but others are even higher. For example, both Donegal and Tipperary have baselines of about €25 million.

A national working group was looking in 2018 at revising these baselines. After some delays and twists and turns, that review is back on, and due to finish this month, the department spokesperson said.

Thinking about and working on the report are representatives of local authorities, the Department of Public Expenditure, and the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, says the department spokesperson.

Dublin City Council put together a submission to this group, making its case for a higher baseline number, and also for a reform of the system for determining these numbers.

It calls the system for determining the baseline numbers “somewhat arbitrary and ill-defined”.

The system “bears no reflection of the relative needs or funding requirements of each individual council in any given year and its retention results in councils’ funding effectively being frozen at a point in time with no consideration of rising costs of other expenditure pressures”, the submission says.

The working group is due to finish its work by the end of this month, and send recommendations to the minister “shortly thereafter”, the department spokesperson said.

“While it is intended that there will be a new baseline allocation model in place in time for 2024 Local Property Tax allocations; this will be subject to the recommendations of the working group and Ministerial approval,” he said.

That review of baseline local government funding is focused on a narrow issue, to do with just a sliver of the council’s funding pie.

But the council’s submission to the working group, and the discussion at the March finance committee meeting when councillors reviewed it, spread outwards from there to a much more fundamental issue: the lack of local control over local councils.

Perhaps the local property tax is a good example of this.

The council doesn’t have control of how much local property tax revenue it gets. They got that bump this year, and the government just snatched almost all of it away.

The council also doesn’t have control of how it spends most of what it does get. Its “share” of local property tax is about €95.6 million, but it only gets to decide how to spend €7 million of that, it says.

It’s in this context that Gilliland, the Labour councillor, called in March for the end to the annual debate over what level to set the local property tax rate at.

Getting rid of the council’s power to vary the local property tax rate is outside the scope of the baseline funding review, the department spokesperson said, but as of last year councils no longer need to set the rate every year, they could set it for multiple years.

At the meeting in March, Séamas McGrattan, the Sinn Féin councillor, and Paddy McCartan, the Fine Gael councillor, found some common ground in their frustration with the local property tax system.

“I know Séamas’ party want to abolish the local property tax altogether,” McCartan said. “There might actually be some merit in that if they came up with another alternative.”

“Go raibh maith agat Paddy, I told you that 10 years ago,” McGrattan said, laughing.