Who will sit on the advisory board set to shape the future of Dublin city centre?

Seven areas of expertise should be represented, said a recent council report.

Few of the photos have seen the light of day since they were originally taken, in 1980–83. Now they’re due to be presented to the Irish Queer Archive.

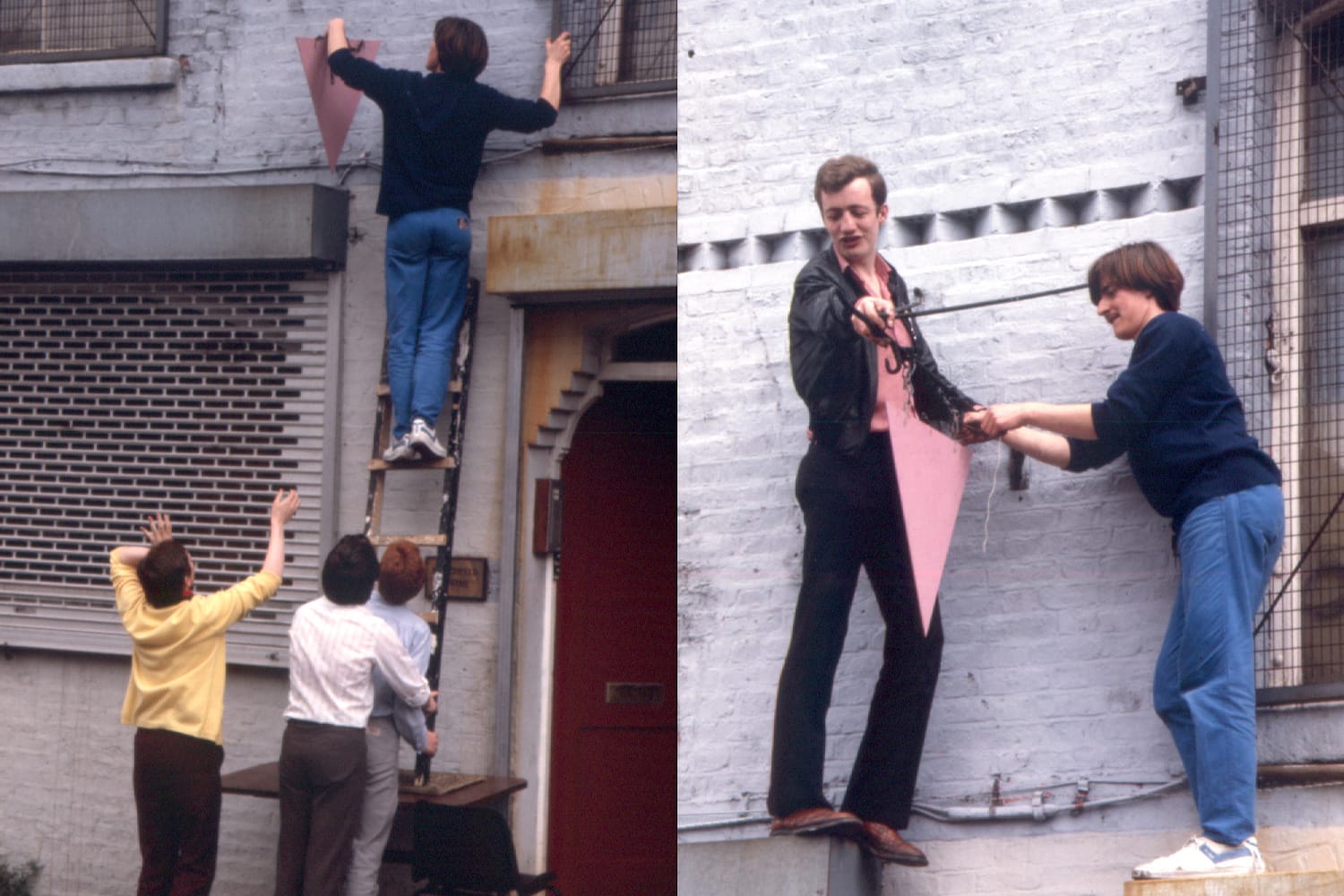

On 20 June 1981, a 20-year old Tonie Walsh climbed onto the rusted rectangular overhang above the front entrance of the Hirschfeld Centre to hang a pink triangle sign.

He scaled a wooden ladder, which was propped up on a school desk outside the city’s then-foremost LGBT social centre at 10 Fownes Street in Temple Bar.

With the assistance of a friend, who got up on a nearby metal canopy over a ground-floor window, he put the symbol – a reclaimed badge of shame used in concentration camps – on display.

As he recalls that Saturday, while seated in the Irish Film Institute café three streets from the centre’s former location, he expresses uncertainty. Walsh isn’t sure if it was the first or second time the sign went up.

It had to come down once, says the journalist, activist and DJ, because the centre’s members hadn’t yet taken a vote on it.

“Some objected to having a big hot pink sign,” he says, laughing. “The gays are in there!”

Hanging the pink triangle was a simple but radical statement of the LGBT community’s presence in 1980s Ireland. Still, the moment is documented in just two photographs, both captured from the other side of the street by the late Daniel Wood.

Known to his peers as Don Wood, the photographer was a regular of the Hirschfeld Centre, where he would shoot its day-to-day and the more momentous events, such as the earliest Irish pride marches.

Few of the photos have seen the light of day since they were originally taken.

But now Wood’s photography from 1980 to 1983 is due to be presented to the Irish Queer Archive in the National Library of Ireland.

The work offers a rare insight into Irish queer history, says Walsh. “You could count on one hand the number of people either unconsciously or deliberately documenting LGBT social and political life back in the early 70s and 80s.”

Don Wood hasn’t been a widely known name in the chronicles of Irish LGBT history. Before the Irish Queer Archive project was first announced in 2017, his name couldn’t be linked to the community, past or present, online.

Wood was from Dublin, and lived in both Cabra and Stoneybatter, according to his death notice.

He was a professional photographer who often travelled the globe, delivering lectures for major camera manufacturers, says activist Karl Hayden.

“He went all over the place, like Tokyo and São Paulo, and took photos of the scenery, of men,” says Hayden. “But they weren’t of any relevance to the community here.”

Wood had been loosely involved in the city’s LGBT community since the 1970s, Hayden says. According to Walsh, he was associated with the leather scene.

Wood kept to himself a lot in the centre, says Eamon Somers, the novelist and former president of the National Gay Federation of Ireland.

“He wasn’t a volunteer or on any committee,” he says. “I was kind of intimidated by him, but he wasn’t unfriendly.”

Wood was usually hovering about in the background, Walsh says, yet there was something distinctive about him.

“He was very dapper, very polite and charming, and he had incredible teeth, redolent of the dental work you get done in the States,” says Walsh.

Ironically, Walsh says he never remembers seeing him with a camera. “It’s the mark of a good photographer that I never actually noticed,” he says.

Hayden, who was delegated the task of archiving his work, first encountered Wood in the early 90s, several years after the Hirschfeld Centre had burned down in 1987.

The pair were a full generation apart, with Hayden his younger. And Hayden only knew Wood as a professional photographer, the activist said recently in a busy Starbucks at the top of Harcourt Street.

“I didn’t think Don had any involvement in the LGBT community whatsoever at any time,” he said.

It caught Hayden by surprise when Wood informed him that he had been asked by Senator David Norris to photograph a handful of events based around the centre during the early 1980s. “This was news to me.”

When Hayden first became aware of this archive of photographs from within the Hirschfeld Centre, he was led to understand that Wood’s photography was not intended for publication at the time they were taken.

He thinks Wood took the photos purely to keep a record of events, he says, such as the pride marches.

“And maybe, also there was an element of … if anything happened, we would have photographs of what happened,” says Hayden.

It was not a period during which many within the centre were open to the idea of sharing private photographs, he says. The early 1980s were rife with fear and paranoia.

During the time Wood documented life around the centre, in 1982, both Charles Self and Declan Flynn were killed in homophobic attacks, he says.

Self’s murder at his home in Monkstown prompted an aggressive investigation by Gardai, which intruded into many people’s private lives, Hayden says.

“There was a sense that Gardaí were using it as an opportunity to gain intelligence about the LGBT community,” he says. “Finding out who was and wasn’t gay.”

As such, many in the community were cautious about having images from their personal lives published, he says. “Photographs would be incredibly useful to Gardaí. So, David asked Don if he would not make them publicly available.”

Wood held onto the collection even after homosexuality was decriminalised in 1993, Hayden says. “He was not going to let go of them until David Norris told him it was okay to do.”

Hayden wasn’t particularly motivated at the time to approach Norris and ask for the photos to be released, he says. “I hadn’t even seen them or had a sense of their importance at all.”

For more than two decades, they remained in Wood’s storage, according to Hayden. But occasionally, the photographer would bring up the fact he had them.

In the aftermath of the Marriage Equality referendum in 2015, Wood became unwell, Hayden says. “Unfortunately for someone who worked in a visual medium, it was his eyesight that began to go.”

Wood was aware that Hayden had played an integral role in archiving the referendum.

The photographer delegated to him the task of collecting his own work, with a view to being handed over to the Irish Queer Archive.

A handful of images were first shared online by the archive in July 2017, at which point the project was first announced.

But the process was slow, Hayden says. Wood never got around to providing him the full collection – and in November 2019, he passed away.

Only after Wood’s death did his partner find the full trove of photographs, passing them along to Hayden to archive.

Eamon Somers sits in the corner of Metro café at the top of South William Street. He scrolls through a series of pdf files, showing the Don Wood Photographic Collection.

He spots himself, pictured at meetings and marching on the streets and begins to reflect on the early days.

He had come out as gay in 1977 and first went to the Hirschfeld Centre not long after it was opened in 1979.

He hadn’t been political beforehand, he says, but quickly became deeply involved in its management.

Within a year he went from being a volunteer to a committee member to being asked by David Norris to replace him as president. “Mine was a bizarre, meteoric rise,” he says.

As he scans through Wood’s images, he spots himself leafleting passers-by on a pre-pedestrianised Grafton Street.

“People talk about 1983 being the first Gay Pride march,” he says. “But Tonie and I were out, walking down Grafton Street in ’80, handing out leaflets.”

Those early marches were small, he says. “It was scary. I never had any confrontation. People might shout, and you’d shout back or ignore them depending on if they looked like trouble.”

The collection offers glimpses of early political actions. It covers the former chief psychiatrist of the Eastern Health Board unveiling the centre’s plaque, and a late-night editing session on the magazine In-Touch, with Senator Norris proofreading copy.

Wood’s lens also picks up on trivial nuggets, such as the backdrop of the centre’s nightclub Flikkers, a recycled golden set originally used by RTÉ for its 1979 National Song Contest.

Walsh emphasises Wood’s importance as a documentarian, reflecting on the scant media coverage of the first major pride parade in 1983.

They were studiously ignored, he says. “For the first time, 150 lesbians, gay men and some transgender women marched strutting to the GPO, holding up traffic.”

But, as he reflects on the significance of Wood’s work, what produces an even stronger reaction are the photographs of smiling couples.

“I mean, how many images of loving same-sex couples can you recall from that period in Ireland?” he says. “Two men, two women negotiating desire in a semi-public-private environment. It’s just really rare.”