On the walls of a Kilbarrack health centre, an artist pays tribute to the beautiful ordinary

Paul MacCormaic says he hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in nearby sights, passed by everyday.

Gay activists say guards took the murder of Charles Self as an opportunity to work up dossiers on at least 1,500 gay men. “What murder has 1,500 suspects?”

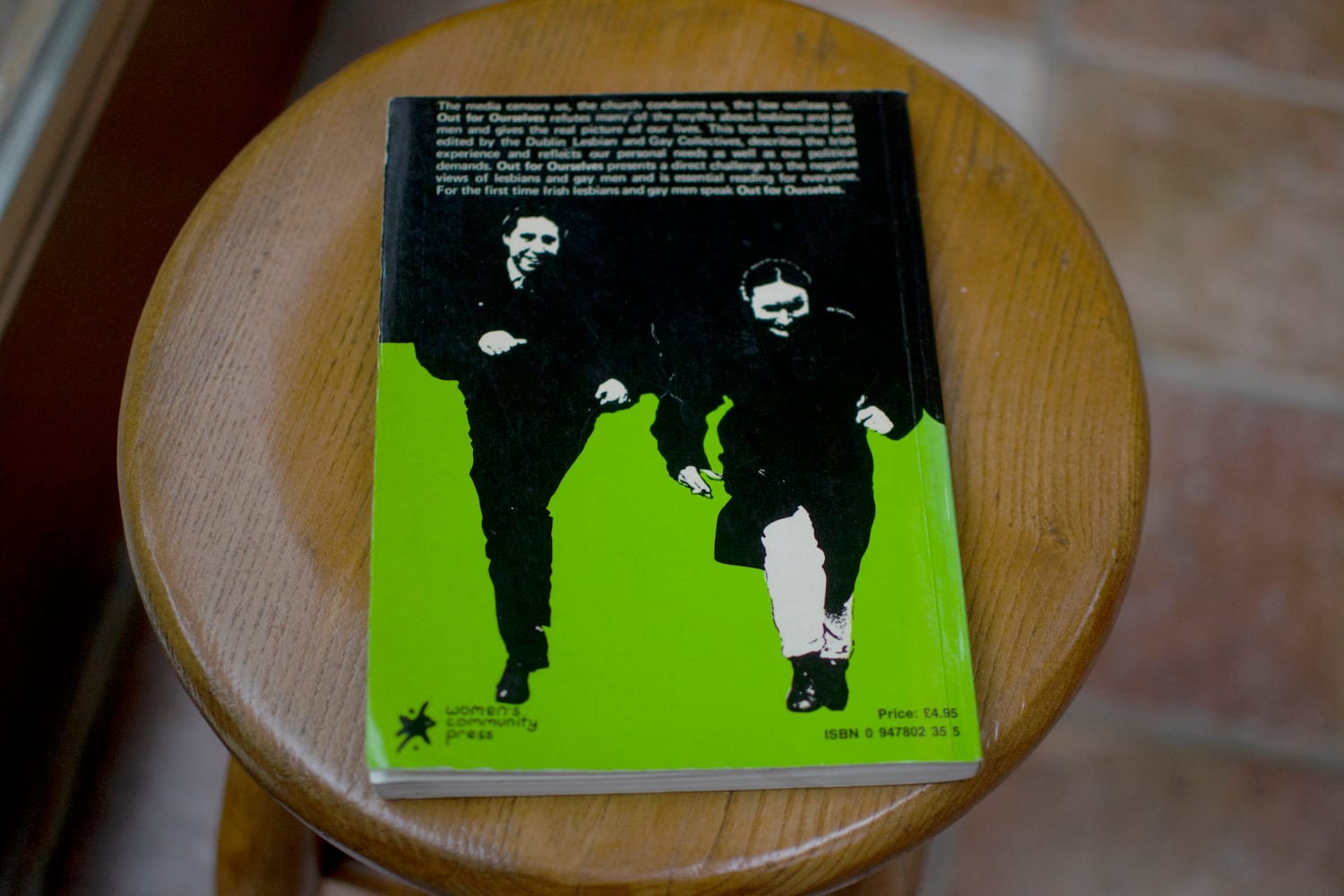

“That’s me on the back,” says Bill Foley, sitting on a large sofa in the living room of his home in Ranelagh.

A nearby book has a photo of a happy pair on the back cover, and a man and a woman running carefree on the front.

“Out For Ourselves” reads the book’s title in green type. “The Lives of Irish Lesbians & Gay Men”, says the subtitle on the bottom in black.

The book, dating from 1986, was written and edited by a group of activists at Dublin Lesbian and Gay Men’s Collective, including Foley.

One chapter is on the murder of Charles Self on 20 January 1982.

Self, a gay set designer, worked for RTÉ. But the short chapter is mainly about An Garda Síochána’s investigation into his killing and how it turned into a campaign of harassing gay men.

Gardaí never found Self’s murderer. But they interviewed many gay men as part of the search.

An article from 18 August 1982 in the Irish Press newspaper had reported a senior Garda officer as having said that “thousands of people were questioned about the murder of Mr. Self”.

Gay activists now and at the time said the Gardaí interviewed, photographed and fingerprinted 1,500 gay men, while the guards say the case involved “over 1,500 jobs” which included interviews too.

“What murder has 1,500 suspects?” says Foley, resting his blue cup on the sofa’s arm.

Gardaí has held on to everything they gathered. “As this is an ongoing active Criminal Investigation all material collected is retained pending any possible criminal prosecution,” a spokesperson said.

Now that they know Gardaí still has the files of all those old interviews, older gay activists who remember the aftermath of Self’s murder are debating what should happen to those records.

“It became clear that the investigation was more concerned with compiling a file on gay men than it was with solving the murder,” says the chapter on Charles Self in Out For Ourselves.

There’s a photo of a picket outside Pearse Street Garda Station on 13 March 1982. Foley and other activists had organised it to protest Garda harassment, he says.

Foley, who was in his early 20s and worked as a paralegal at the time, says they’d linked up with trade unions, women’s groups and political activism groups.

The guards never interviewed Foley, he says, probably because he had a partner (who has since passed away).

“I suspect they were looking at single men,” says Foley, who keeps framed photographs of himself and his partner, both looking sharp and young, on a little table next to a white chair in a bright room facing his garden.

The protest photo in the book shows three guards standing on the steps of the Garda station, watching over the protestors. Two guards have their hands in their pockets. A woman is standing right before them, carrying a small child.

Behind her, another woman holds a sign that says, “Hassle The Murderer Not The Victims”.

Says Foley: “They kind of just let us get on with it. We were doing a perfectly legal demonstration outside the Garda station; I think it caused some embarrassment for them actually.”

At the time of Self’s murder, Cathal Kerrigan was living in Fairview.

He and his then-partner Máirtín Mac an Ghoill were staunch political activists involved in a group called Gays Against H-Block/Armagh, which was active between 1979 to 1982 to support hunger strikes of inmates at H-Block prison in Northern Ireland, including Bobby Sands.

Their activism was contentious enough to capture the guards’ attention often, said Kerrigan recently, sitting outside Love Supreme café in Stoneybatter, eating a sandwich.

“Máirtín was already known to the police because he was a much deeper activist than I was,” says Kerrigan.

After Self’s murder, once they realised that the guards were interviewing and fingerprinting gay men in droves, Kerrigan and fellow activists got organised anddistributed a leaflet.

“Since the murder of Charles Self at the very least 500 gay people have been questioned by the Gardaí and the Special Branch. And what have we been asked about? Very little about the murder; a lot about our personal lives,” it says.

It goes on to advise readers of their rights. “Do not give your fingerprints or allow yourself to be photographed. If you have already made a statement, or have been photographed, consult a solicitor immediately,” it says, for example.

On the morning of 1 March 1982, Kerrigan was arrested “under section 30 of the Offences against the State Act”, according to a letter from then-Taoiseach Charlie Haughey in response to his complaint about the arrest and the guards’ treatment of him.

They let him go on the same evening, and the guards didn’t ask him about Self’s murder, says Kerrigan.

“They were claiming that there was an event that happened that was criminal to do with terrorism, and they wanted to know if I was involved,” he says.

But he always wondered about the timing of it all and how it coincided with investigation en masse of gay men over Self’s murder, and his activism and organising work against that, says Kerrigan.

He wondered if the guards wanted to intimidate people into stopping.

People might dismiss that as grandiose or paranoia, he says, smiling. “But I think you could say that it’s quite likely that there’s some kind of potential connectivity.”

Newspaper reports from the time followed the investigation and criticism of how the guards were handling it.

“Some of Mr Self’s associates were members of the homosexual community”, said an article in the Irish Independent, attributing the information to Detective Superintendent Michael Sullivan.

So Gardaí “had visited a number of gay clubs in Dublin to carry out inquiries”, the 25 January 1982 article said.

Det. Supt. Sullivan had denied a claim by David Norris that Gardaí had asked the National Gay Federation to hand over its membership list, it says.

An article from 25 March 1982 in the Irish Press conveyed gay activists’ concerns about the guards’ handling of the investigation, and how it had turned into an opportunity to build dossiers on gay men.

It reports on a public meeting held in Dublin the previous night, “called to discuss the alleged harassment of gay people by gardaí during the investigation”, it says.

At the meeting, Eamon Somers, then president of the National Gay Federation, is reported to have said that “people are being pressurised specifically because they are gay, and asked questions that are not relevant to the crime”.

In an article from 23 March 1982 in the Irish Press, the guards deny the accusations. “The allegations are completely untrue. There was no compulsion on anyone to make a statement and there was no intimidation used on anyone as far as I know,” it reports Superintendent Hubert Reynolds as having said.

Foley, the man in Ranelagh, says he remembers reading in the papers that the guards said after the protest outside Pearse Street Garda station on 13 March 1982 that they’d get rid of the personal information they had gathered on gay men as part of the murder probe.

“But we were never reassured as a community that it actually happened,” says Foley.

Indeed, at the public meeting on 24 March 1982, Mike Kelly, of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, “said what worried him was the difficulty of ensuring that records from the investigation would be destroyed”, according to the Irish Press article.

“We must look for guarantees from the gardaí, from the Minister for Justice, and if necessary from the Taoiseach himself to ensure that all irrelevant evidence will be destroyed,” the article quotes Kelly as saying.

But, 40 years on, Gardaí is apparently still holding onto the info gathered through those 1,500 or so interviews with gay men that they did in the course of their investigation into the still-unsolved murder of Charles Self.

The invasive nature of the questions Gardaí asked people back then makes the data all the more personal, Foley says.

People talked about the intimidation during questioning, he says. “They were asked about their sex lives and what they did in bed, and they were jeered about it, you know? All of that obviously irrelevant to the investigation.”

Foley points to a recently proposed scheme by the Minister for Justice, Fine Gael’s Helen McEntee TD, which is aimed at wiping the criminal convictions of gay and bisexual men prosecuted for having consensual sex.

That’s an opportunity, Foley says, for the Department of Justice to see that the Gardaí dispose of people’s data gathered as part of the investigation into Self’s murder. “I think this could go into it because this investigation was a disregard of human rights.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Justice didn’t say if it would consider disposing of the data. The working group established by McEntee to examine the proposal around wiping convictions has recently published a progress report, they said.

Kieran Rose, a gay activist and a member of that working group, says the scheme is about giving gay men who were spied on and arrested by the Gardaí while having sex, sometimes in the privacy of their own homes, a chance to erase that as a criminal background.

Interview transcriptions and gay men’s records compiled after Self’s murder document state oppression of queer people and shouldn’t be destroyed, says Rose.

Rose says he has a history background. “So I think the interviews and all that was done with gay men is a huge historical resource. It would be just fascinating to look at them as a research project.”

The Guards should give the public access to the records but keep people anonymous, says Rose.

He points to a redress scheme and its use for the survivors of mother and baby homes. The state could consider something similar here, he says, albeit maybe the guards can’t do much if they say the case is still active.

Kerrigan, the man who was arrested in Fairview, is with Rose in demanding public access to the records instead of destroying them.

He says they could give people – or if they have passed on, their relatives – the option of destroying their information or archiving it and making it available for the world to see.

It is history, Kerrigan says and, if treated sensitively, these historical documents should be preserved. “People should be able to see how people were treated and what happened,” he says.

A Garda spokesperson said: “Any person wishing to apply for details of their personal data held by An Garda Siochana can apply for same under the Data Protection Act; the process to do so is through the An Garda Síochána, Data Protection Unit.”

But the right to access personal records under the law is limited in some cases, they said, like when data handover might undermine or prejudice a criminal investigation or prosecution.

They didn’t say if this applies to personal records of gay men interviewed as part of Self’s murder investigation.