On the walls of a Kilbarrack health centre, an artist pays tribute to the beautiful ordinary

Paul MacCormaic says he hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in nearby sights, passed by everyday.

“Can I really translate the essence of my humanity and my being into a digital version of myself?” Aisling Phelan asks.

The interior of Unit 4 on James Joyce Street glows violet blue one evening in late March.

The council-owned incubation space is illuminated by a projector’s beam and some icy-blue fairy lights around its doors and skirting boards, which draws in a crowd of some 20 people.

They have come for the inaugural DIY Film Club, a monthly event devoted to the screening of experimental films.

The film club is curated by a collective of artists, and is hosted by Dublin Modular, a non-profit electronic music and visual arts organisation.

Post-lockdown, the club offers attendees a chance to build a real-world community, seeing on a large screen underground shorts that might otherwise be stuck online.

Included on the evening’s bill is a disorienting virtual-reality music video directed by multi-disciplinary artist Aisling Phelan.

Phelan’s work spans 3D animation, photography and music, and grapples with questions of identity, connection and intimacy in both digital and physical spaces.

Chief among her concerns is the matter of what is lost in the transition between these two realities, and in a moment when society is addled by that thought, the 22-year-old’s dizzying imagination seeks to offer insights.

“Can I really translate the essence of my humanity and my being into a digital version of myself?” she asks.

Phelan created the music video to tie in with the release of the band I Am the Main Character’s debut single, “Gold (I Die at the End)”.

It was her pandemic project, she says. Pre-Covid “photography was my main thing”.

Quietly, she sits in the back row, wearing a pair of long, thin sunglasses and a puffy coat.

For five minutes, the video transports the audience into a jarring alternative realm, consisting of chrome hallways, glitching walls and waiting rooms filled with people whose body parts warp.

The labyrinth she constructs is akin to the old Windows 3D Maze screensaver.

During the trip, the viewer encounters a disembodied rotating golden heart, featureless humans who swim and levitate, and a blocky giraffe figure.

Towards the climax, the fourth wall is revealed to be a pair of eyelids, which open to show a trio of masked identical surgeons.

A text appears on screen, saying “Game Over, You Died”, switching fonts in quick succession, before the viewer is plunged into a glitching vortex.

Two and a half months later, Phelan takes a seat at a table in the Concourse building, a student’s common area at the National College of Art and Design (NCAD).

It is lunchtime. Her graduation show is only a couple of hours away.

The Concourse is filled with boxes of vegan pizza and, intermittently, students pass by and cautiously pick up slices as if they are being observed.

Rubber stamped on Phelan’s cheek is the date, June 8th, 2022. She marks herself daily, comparing it to a digital timestamp.

Born and raised in the Wicklow Mountains, Phelan says she comes from a musical background. Her brothers are producers and musicians, and so is she, often recording under the moniker Xulfer Dica.

So she had a choice in school, she says. “Do I study music or do I study art?”

She opted for art. “Because music is just so in my blood at this stage, I felt I was never going to lose that. I was drawn to understand more, how to make and understand art.”

Her artwork is concept driven, she says. “I wasn’t making work for the sake of making work,” she says. “It wasn’t me.”

“I couldn’t paint. I can’t draw, and I began leaning towards Photoshop, photography, shooting on film and developing my own negatives,” she says.

In 2019, Phelan photographed scenes from Dublin’s alternative nightlife on 35mm film. What she documented was a sweaty and joyfully chaotic spirit of community.

Released in late 2021 as a series titled Intimissme, in March, the project was shortlisted for inclusion in the Belfast Photo Festival.

Her first foray into virtual reality came in December 2019, when she staged a live VR performance in the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

The idea, she says, was to meet and communicate with her audience in a virtual space. Once the piece had wrapped then, she didn’t presume this was the route she was heading down.

“I was like, ‘Okay, cool, I did a VR thing. Now let’s get back to photography.’”

In March 2020, Phelan was in the middle of developing a new series of photographs, as the first national lockdown was instated.

Without access to a darkroom, she decided to let that project go, she says. She reverted to using 3D software and received the commission to make the I Am the Main Character music video.

The band’s lead vocalist, Sam Burton, says that he had come across Phelan when she photographed one of their gigs at Sin É. He had also seen live visuals she produced for a streamed performance by the rapper Traashboo.

“We had a rough concept in mind,” Burton says. “It was supposed to be about a person who believed that living in a morally right way could lead them to attaining a literal heart of gold, which they could then extract and sell for money.”

At first, Phelan was going to produce a work that echoed the lyrics in a literal way, Burton says. “But instead, she opted for something different to make it an equal collaboration.”

“She went for a sort of chase. The viewer is brought into a pseudo-game, where they are chasing the golden heart, which is constantly out of reach,” he says.

Phelan says she worked on the video for seven months. “It was nice to have a big project where I didn’t need to go anywhere for.”

“Being very conceptual, even with photography, I didn’t feel it was communicating the ideas I was coming up with, whereas, with the nature of 3D, anything is possible,” Phelan says.

On Wednesday 8 June, Phelan’s latest work, an interactive installation called “Dual Reality” began playing on a loop in a blacked-out space on the top floor of NCAD.

“Dual Reality” unrolls like a Beckettian conversation between two characters, whose voices are pre-recorded. There is the real-life version of Phelan and a computer-generated rendering of herself.

“Your identity on the computer is the sum of your distributed presence,” says the computer-generated version of Phelan, coldly.

The recorded voice of Phelan replies with a question: “Through this remaking of my online self, how can I know what dies in the process?”

“We remember so you don’t forget,” the bot says.

“But what if I don’t want you to remember?” says the exasperated voice of Phelan. “Do you even have the ability to forget? Do I have control over what you forget and what you remember?”

“You have been denied the right to be forgotten,” the bot says back. “When the body goes, the mask stays.”

“But what version of us is being remembered, is it you or me?” Phelan wonders.

Representing the pair are two installations, on either end of the room.

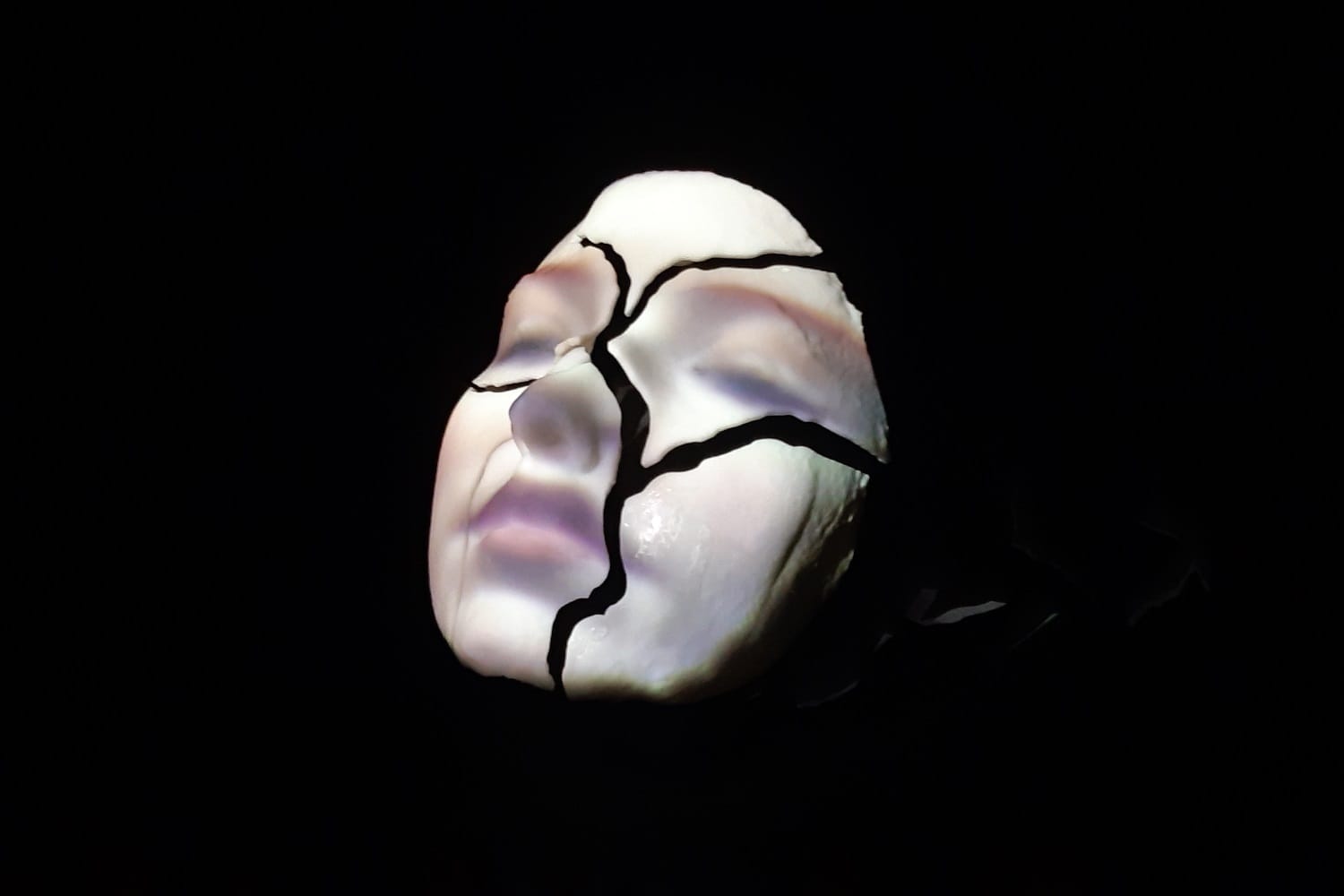

To one side is a white 3D print of Phelan’s face. It is fractured into six pieces, and images of her with different expressions are projected against the surface.

On the opposite side, there is a triptych of screens. Each of these also features a scan of Phelan’s face. The central screen offers a view of the front, while those to the left and right showing her side profile, her cheek here rubber-stamped March 24th, 2022.

The screens are activated by motion sensors, which cause the faces to fragment or reassemble as the viewer moves about the room.

If one person is present, one face will fragment. For the full experience, there must be at least three people in the space.

Phelan was going to call the piece “Distributed Presence”, with a nod towards the work of media theorist Anne Friedberg.

Says Phelan: “We have parts of ourselves in a lot of different spaces that we don’t really understand.”

She cites the example of HTTP cookies, the small blocks of data stored on a device after online sessions.

“If you’ve ever selected ‘I Agree’ on a site, you’re not agreeing to give your cookies to that website,” she says. “You’re agreeing for that website to give your cookies to hundreds of other people.”

That idea of the distribution of personal information out into the ether, Phelan says, is why in “Dual Reality” she focuses on the idea of fragmentation and enables participants to deconstruct her face through their movement.

“I don’t have control over what people do to my digital self,” she says.

Swedish artist Ingmar Kviele, who performs under the name N I T E F I S H, says he is drawn to Phelan’s “cloud-based ethereal” imagery and her explorations of digital identity.

“Now, we have a second artificial identity that we create,” he says. “We have an avatar of ourselves, and we have ourselves. Both of them are in a bit of unison, and her work captures that.”

Phelan contributed the artwork for Kviele’s 2021 single “Youth Offgrid”, a track that merges the hardcore techno-variant gabber with uplifting psychedelic electronica.

The result of their collaboration is an image of Kviele wearing a pair of black Speedo goggles, surrounded by leaves, lily pads, flowers and synths.

“She was the person most suited to explore the idea of a utopian society, something which is digital but not dystopian,” he says.

Aligning her work with the late electronic artist and producer Sophie, Kviele says, Phelan is not monotonously dour, but capable of recognising the multifaceted experience of exploring digital spaces.

“She looks at artificiality and digitalised personae as a potential source of empowerment,” he says. “And I thought that complexity would lend itself to the track.”

After 8pm on the evening of Phelan’s graduation show, droves of people ascend the staircase from NCAD’s bustling courtyard to see “Dual Reality”.

Phelan stands outside, dressed in a matching multi-coloured shirt and trousers combo, featuring a pattern of fruits and vegetables.

She is awestruck by the reception, she says, particularly a small blue and red sticker by the entrance denoting that the piece has just been longlisted for the RDS Visual Art Awards.

Inside the exhibition space, the pre-recording of the real Phelan is being told by her bot that it understands her better than she knows herself.

The real Phelan asks why this digital self thinks she is into SUVs, auto racing and the Philippine Stock Exchange. “What kind of person do you think I am?”