What’s happened with Manna’s plan to expand its drone delivery service across Dublin?

It still only has one base, in Dublin 15, with planning permission – and that’s due to expire this year.

Martha Fitzgerald says she was inspired by the 1987 film The Witches of Eastwick to write a spooky, magical musical about three women, set in Dublin – The Witches of East Wall.

Martha Fitzgerald sits alone amid the empty audience seating, close to the wall, her head bent. She looks up at once when the door swings.

“Just to let you know, I’m a bit nervous,” she said steadily, smoothing the folds of her trousers with her hands.

Composer Ru Mew walks out from the backstage doorway of the New Theatre on Essex Street. He’s dressed all in black and, sitting on the edge of the theatre seats, he offers Fitzgerald a comforting look.

In 15 minutes, the seats will be filled with the audience to watch The Witches of East Wall, a play written and directed by Fitzgerald.

But it’s not a full performance, she hastens. “It’s an unfinished piece. Still rough around the edges, but we’re just looking for feedback.”

She feels vulnerable, she says. Mew reassures her.

“There’s no normal or abnormal way to make a piece of theatre, I suppose,” says Fitzgerland thoughtfully, gazing out at the stage.

Fitzgerald says she was inspired by the 1987 film The Witches of Eastwick to write a spooky, magical musical about three women, This, though, would be set in Dublin – hence, East Wall.

Three roommates embody explorations of female friendship, magic, history and anything else that came to mind.

“What are some random things that I find vaguely interesting, and I threw it all in a pot,” she says. One song’s about Twitter. “That’s literally like a fucking hot take, turned into a song.”

The songs came first. The script was much harder, she says.

She brought her lyrics to Mew, who composed music.

They were both inspired by the musical Hamilton, she says, copying techniques.

“I think in an ideal version it would be almost sung entirely, like Les Mis,” she says. “I would actually replace some of the scenes and turn them into songs.”

Fitzgerald had written plays before, with production company Fizz and Chips Productions, which she started in 2017 with Mew, Orlaith Ní Chearra, and the play’s assistant director Lindsey Woods.

They found it hard to get into the theatre scene, she says, so they started their own productions.

Fitzgerald had been working abroad, and when she came home she got back into theatre for the first time since college.

“I auditioned for something, met these guys, we started writing songs together, and we were like, ‘We wanna do this forever’, and that’s what happened,” she says.

At the start, she found rehearsed readings fascinating, she says.

“You’re getting a little window to the creative process. It feels almost like it’s like demystifying it for you. So like, that’s kind of exciting as well.”

That’s partly why she’s holding a public rehearsed reading now. That, and to have a deadline, she says.

It’s also part of her Arts Council Agility Award, which offers her research and development funding.

“I would say, a small minority of performances would do a public rehearsed reading like this,” she says.

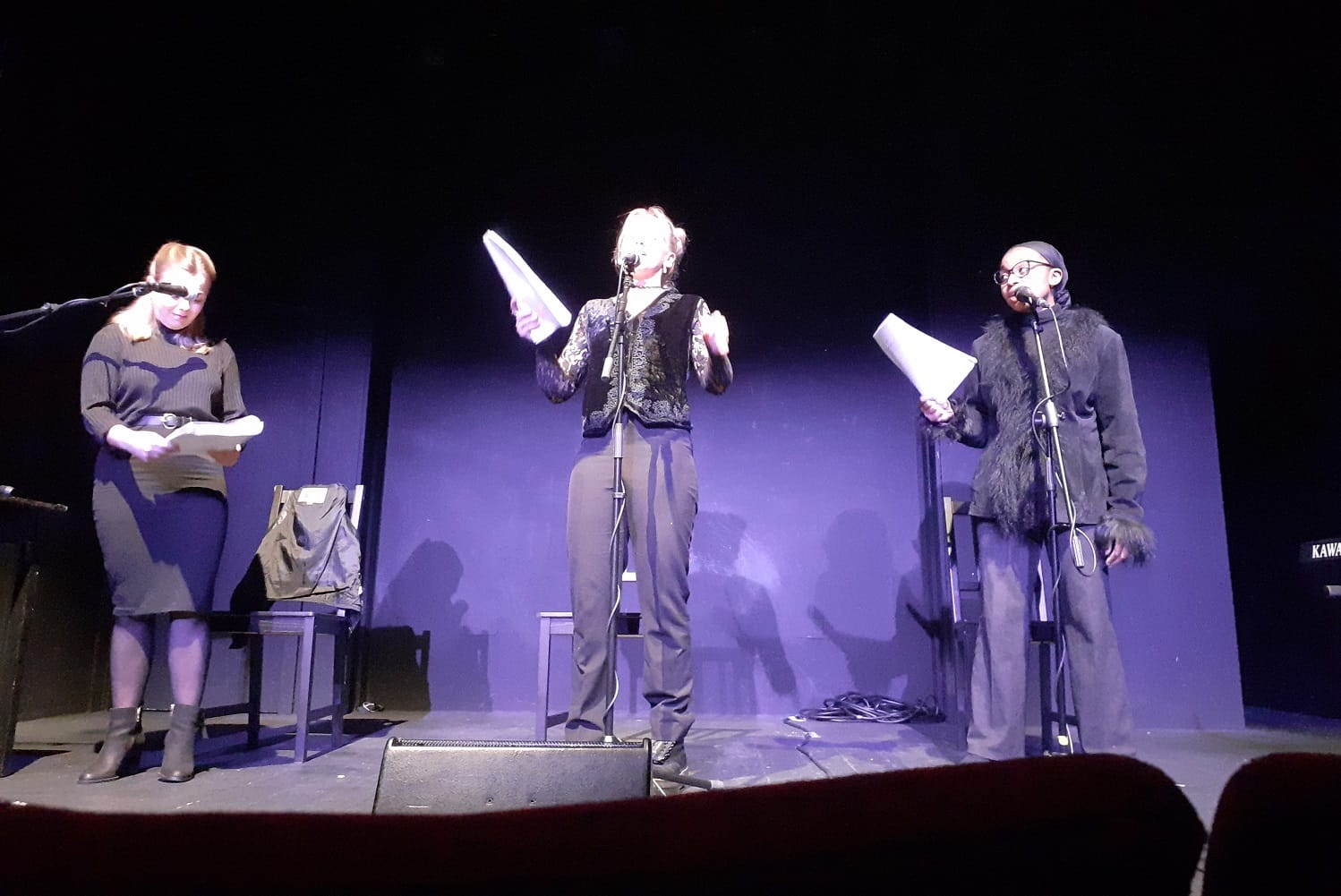

As the audience settles into silence, Fitzgerald hops onto the stage. “Thank you very much for coming,” she says into the middle microphone of three.

Feedback forms will be handed out at the end, she says. “So we’d really appreciate if you could fill them in before you leave. And so we’ll use it in the continued development of the musical.”

“Just to warn anyone who doesn’t already know – it’s not a finished product,” she pauses. “It’s not finished!”

A laugh rumbles from the audience.

“There’ll be scripts on stage. It’ll end at a time when you’re like, why is this over?” she warns.

She gets down from the stage. Behind her, five people, dressed in all black, enter from the doorway and take their seats.

Mew sets his hands to a keyboard, and the first notes begin.

Forty-five minutes later, inside Connolly Books, which any audience leaving the New Theatre spills into, Maude Gilligan and Sean Gildea are bent over a bookstand, filling in a feedback form.

“Which character did you care most about?”

“What, for you, was the central event of the play?”

“Really nice music. Strong characters as well,” says Gildea. “Kind of interested to find out more about Maura, the girl who went missing.”

Gilligan says it ended too soon. “I was ready for the story to keep going.”

“How did the opening scene make you feel? What were your first impressions of the play?”

“What was the single most impressive thing about the play?”

Near the front door, Arthur Riordan, a musical playwright, says he’s going to write that Fitzgerald has a really individual voice.

“The premise that it’s going to hinge around the defenestration of Prague for one thing. That’s intriguing,” he says.

At the other end of the room, Fitzgerald mills about as people congratulate her.

“What, if anything, worked well for you as an audience member?”

“Was there anything you weren’t sure about?”

Beside the history section, Jerry Kildea and Nikki Holmes are having a conversation.

“The key moments in the build-up to the cliffhanger were not punctuated and broadcast enough,” says Kildea.

“It was very engaging. Disappointing that we didn’t get to find out where Maura was,” he says.

Says Holmes: “I thought it was terrific.”

“Would you attend a full production?”

“Any other general comments?”

Outside, shivering in the cold, Brian O’Flynn says he’s seen Fitzgerald’s other plays. “I knew the musical level was always going to be like ridiculously high.”

“Even though we didn’t have the full story, I think everyone was entertained. There were just such funny moments,” he says.

He liked the way the play ended, he says. “I’m kind of filling in all the weird blanks in my head now.”

Inside, someone is talking soberly to Fitzgerald, who nods distractedly.

In Anne’s Bar across from Connolly Books, Fitzgerald tucks herself in, and sips a pint that Mew brought her.

She enjoyed watching her play, she says. “I tried just to let it wash over me. The actors are amazing. I was just really, really impressed.”

That makes it easier, she says. “Even if you’re not sure how you feel about your writing or your direction, you just remind yourself of how great everyone else is.”

“In those moments of insecurity, reminding yourself that in the worst-case scenario, they’re still going to do a great job,” she says.

Now, the completed feedback forms are stacked in the bag at her feet. “It’s easy not to think about them, because I haven’t looked at them yet,” she says.

She’s excited. “Loads of people I love were there so I’m sure it’ll be some nice things.”

But worried, too, that people might point out big issues. “It’s just more labour, do you know what I mean, you’re just like, urgh!”

Any other comments, anything not useful, she’ll have to do her best to disregard, she says, because if people don’t like it, they just don’t like it. “Otherwise, you couldn’t really do it, you’d just curl up and die because you’d take it too personally.”

Mew says he’s not worried about the feedback. “I mean, if people didn’t like it, we need to know why. And we need to know what we need to improve.”

All artists need a test audience even if it’s uncomfortable, says Fitzgerald. “You’re putting art into the world to be watched, and to be spoken about.”

Artists have to be sure they’re not writing into a void, she says. “The most important thing is that you like what you make, but the next most important thing is that even one other person gets it.”

Musicals let you go really weird, says Fitzgerald. “Even if people don’t understand what’s happening, they know what the emotion of the song is, because we have so much context for music.”

Take Little Shop of Horrors. “It’s about man-eating plants that can talk and sing. And people are like, okay cool, that’s what it’s about,” says Fitzgerald.

“People will go with you anywhere, I think,” says Lily Cahill, a friend sitting next to Fitzgerald. “If you’re funny about it, if you’re empathetic, and there’s music.”

Fitzgerald says she just wants to see if some people will be able to come with her into the world of The Witches of East Wall.

“I wanted to see if what I was trying to do was clear to people today. It wasn’t a lot of time to tell, but yeah, that’s what I want,” she says resolutely, sinking back into her seat and her big puffy jacket.

[CORRECTION: This article was updated on 1 December 2021 at 4.07pm to correct the spelling of Lindsey Woods. Apologies for the error.]