Who will sit on the advisory board set to shape the future of Dublin city centre?

Seven areas of expertise should be represented, said a recent council report.

The show contrasts the feeling of being restricted by Covid-19 shutdowns, with the much more serious restrictions faced by refugees.

One painting depicts piles of oversized white Lego blocks in front of a blackboard, and another shows an abandoned classroom with stacks of red chairs.

“No more time for Lego bricks, no more time for musical chairs,” says artist Miriam Mc Connon.

Children displaced by war have lost years of their childhood. “They won’t get them back, there is no compensation,” she says.

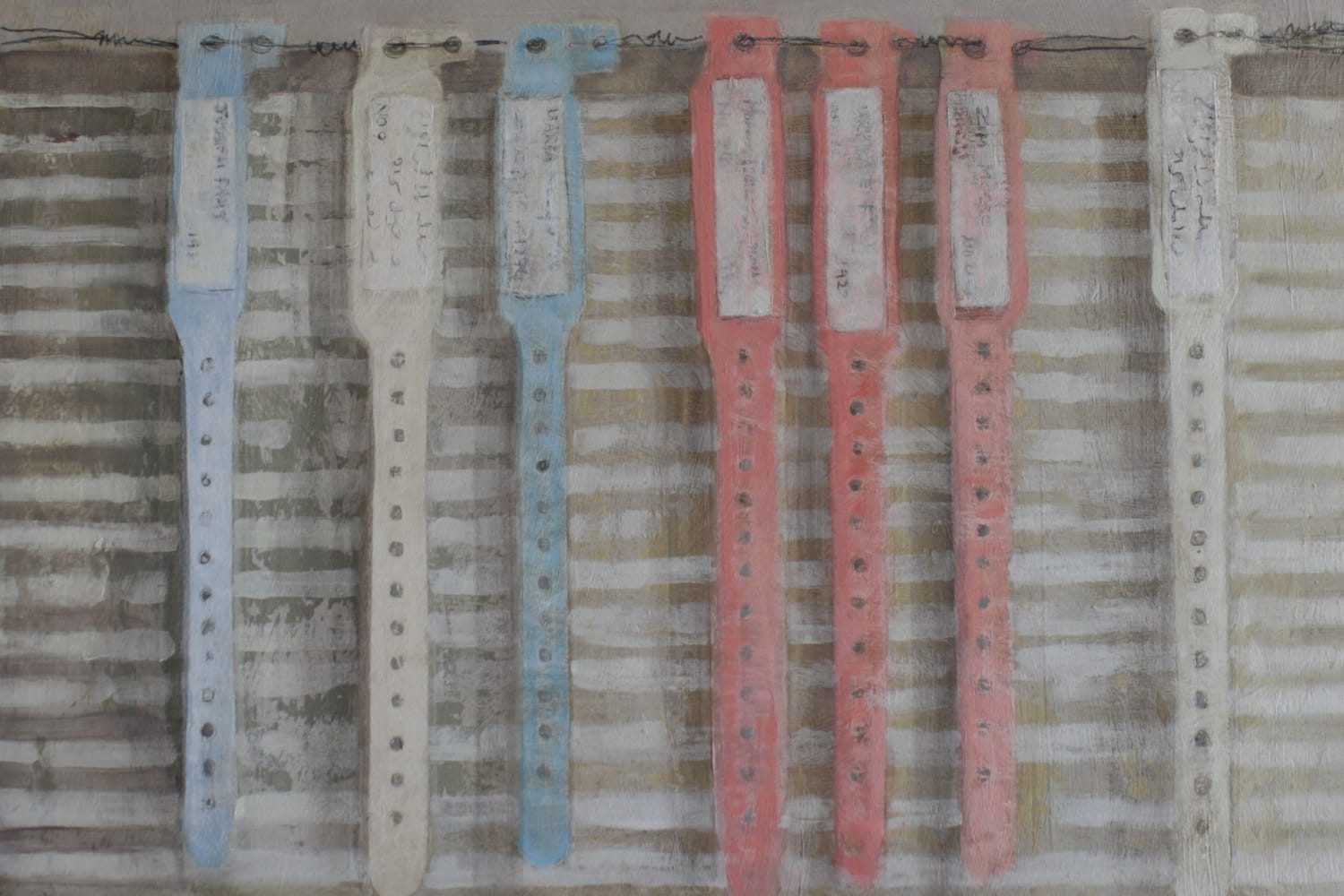

For Displaced Privilege, her upcoming exhibition in the Olivier Cornet Gallery in the north inner-city, Mc Connon explores the experiences of people who have been displaced by war.

The show contrasts the feeling of being restricted by Covid-19 shutdowns with the much more serious restrictions faced by refugees.

“This exhibition serves as a reminder that the freedom of movement, access to medicine and education are indeed a privilege,” says Mc Connon in her artist’s statement.

Dublin-born Mc Connon lives in Cyprus with her husband and children.

The family volunteer in a centre called the Learning Refuge supporting children who have been displaced by helping them with reading, writing and the Greek language, she said on a Zoom call.

Learning the local language and getting an education “allows the children to have other opportunities”, says Mc Connon.

Through her volunteer work and everyday life, she has made a lot of friends who have been displaced, she says.

Many people who have fled the war in Syria, and others who are refugees from north Africa, find their way to Cyprus as it’s nearby, she says.

There are also refugees from earlier waves of displacement, from Lebanon, and some who were displaced in the 1974 conflict with Turkey in Cyprus, she says.

These days, refugees are at first sent to camps, but after a few months they are usually granted a permit to work in specific areas like agriculture or on government schemes, she says.

“People could be a lawyer or a teacher in their own country,” she says.

Like every country there is some bigotry and racism, she says. But mostly “people are kind, they are usually very welcoming”.

When you meet someone from another country, you can learn a lot from them, and it enriches the culture of a host country, she says. “It is an exchange.”

The exhibition explores the “contrast between the life of a refugee and a non refugee”, says Mc Connon.

When Covid-19 restrictions hit, it meant there were a few more commonalities between the refugees and non refugees, she says.

Suddenly everyone’s life was restricted. The difference is that for many refugees, the restrictions will never end, she says.

“We have friends here who haven’t seen their family in nine or 10 years,” she says. In some cases “they don’t know if some of them are alive anymore”.

Society tends to celebrate the stories of displaced people who made successful lives. Like in films about people who fled to the USA during the Second World War, she says.

There isn’t always as much empathy for a young refugee who can’t speak the local language and may struggle, she says.

Traditionally, people often told stories through designs in lace or crochet or in the weave of carpets, says Mc Connon. “They were highly skilled ways of depicting something.”

As in those designs, Mc Connon often repeats images and patterns. That represents the collective experience, the fact that “the story repeats itself”, she says.

Her painting A Syrian Story of Displacement is taken from the weave of a carpet, shown to her by a Syrian woman.

Another painting in the series, A Cypriot Story of Displacement, is taken from a piece of lace a woman from Cyprus showed her, she says.

Both women were displaced by war, but decades apart, she says. They have common experiences but of course each person’s story is unique.

Mc Connon mostly talked to women, she says. “We had informal chats and they would show me some objects and I’d photograph them.”

One woman from Syria handed her a drawing that her daughter had done, showing a house with a family and a swing. “It’s so expressive, this idealistic drawing of a child, what home is,” she says.

The child’s drawing is depicted in the painting No More Time For Learning, and is drawn repeatedly on the blackboard in the abandoned classroom.

Ordinarily, Mc Connon has to do lots of sketches and work slowly towards a finished painting. But sometimes she gets a sudden flash of inspiration.

Like the day when a woman showed her her passport, she says. “She took out a passport and it was open like that,” says Mc Connon, using hands to make a triangle. “I thought it looked like a tent.”

The painting Passport Tents II shows rows of passports making upside-down triangles, like a row of tents.

Some people look at it and think of Covid-19 restrictions, while others see the restrictions that are placed on people who come from outside the EU, she says. “I’ve had British people look at it and think of Brexit.”

Passport Tents II has been selected for the London Biennale, which takes place towards the end of June.

Displaced Privilegeopens online on 23 May, and in real life, by appointment, from 11 June in the Olivier Cornet Gallery on Great Denmark Street in Dublin 1.