After years of work by council, government abruptly spiked policy meant to deliver arts spaces in the city

“It was hugely dispiriting,” says Labour Councillor Darragh Moriarty, who chairs Dublin City Council’s arts committee.

Instead of producing housing where need is greatest, our housing system is producing – by a multiple of three – development on the periphery of settlements.

Since Ireland’s economic resurgence took root in the first half of the 2010s, housing has been playing catch-up.

Employment and population growth have led to a surge in demand for accommodation, and Dublin’s housing system has been unable to cope, with high costs and limited capacity – particularly in the rental sector – threatening the sustainability of the recovery.

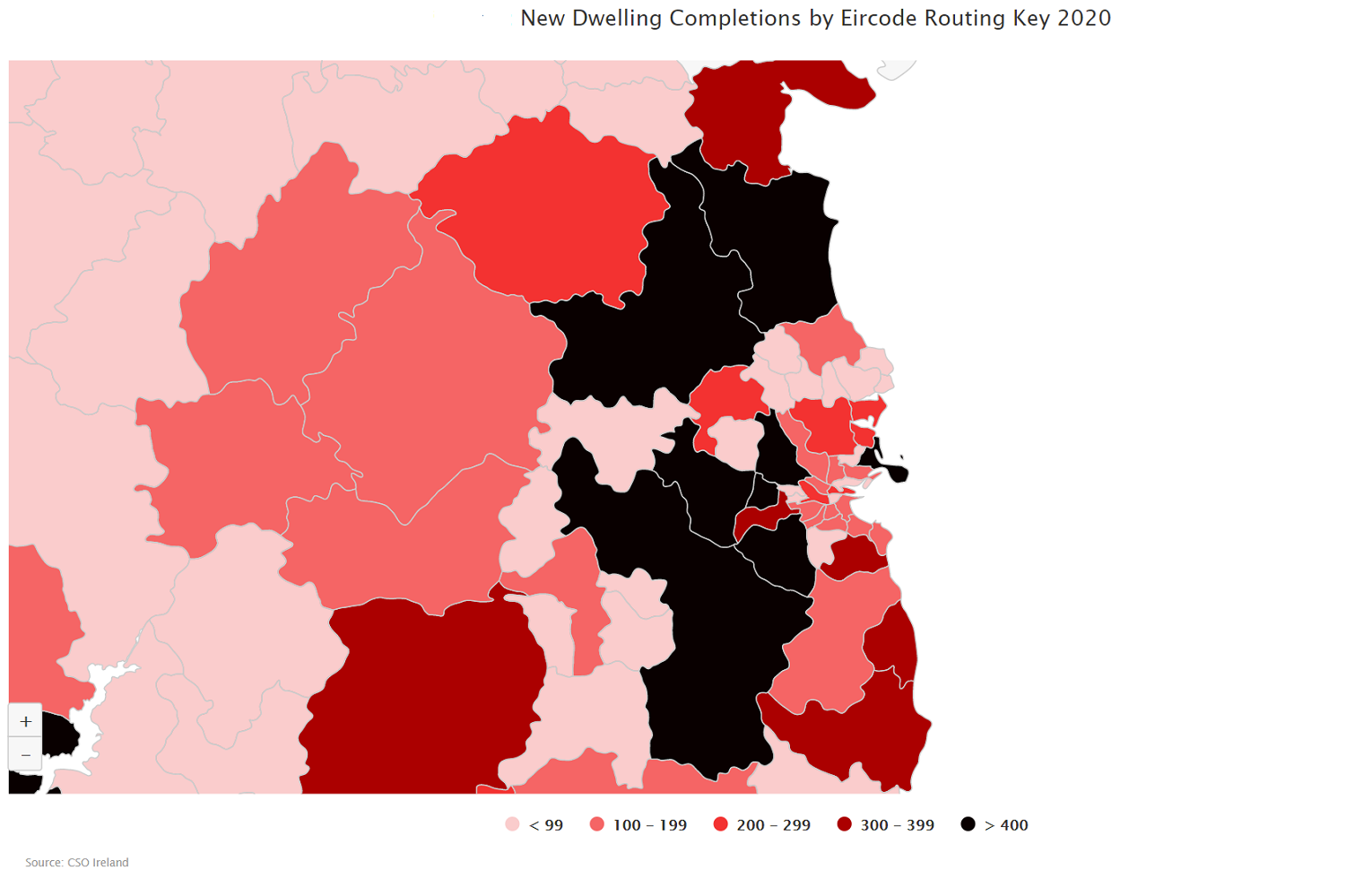

The policy response has focused on numbers, with success or failure typically measured in terms of the annual number of new units delivered nationally. Less attention has been paid to where this new housing is being built, and its implications for other policy areas such as climate, health, and transport.

While the Rebuilding Ireland plan and the National Development Plan both mention the importance of location, the data suggests that these national strategies are not trickling down to impact where new housing is being delivered.

This policy blind spot has allowed a spatial crisis to emerge. Taking Dublin and its periphery as an exemplar of a wider national trend, the location of new housing completions is alarming when compared to where the need for housing is greatest.

The most extreme housing need and population growth is in Dublin city, but the location of new housing development belies this truth. Instead of producing housing where need is greatest, our housing system is producing – by a multiple of three – development on the periphery of settlements.

This problematic trend is most acute for Dublin. According to CSO data, since 2017 there have been 7,024 housing completions on the periphery of Dublin, and 2,458 in Dublin city. Nearly three times the rate.

(In the map below, black represents the areas with most housing completions in 2020.)

More worrying still is that the houses being built on the periphery of Dublin, typically to serve Dublin, are themselves being built on the periphery of settlements.

New housing developments in Naas, Navan, Dunshaughlin, Celbridge and Bray are being built a few kilometres outside these towns. Regionally balanced growth is a good thing, but new housing developments on the edges of towns to serve an urbanised Dublin-based workforce is not.

These developments bake in car-dependency and congestion, make public transport, schools, and doctors’ surgeries unviable, hollow out nearby towns and – from a mental- and physical-health perspective – encourage isolation and sedentary lifestyles.

In short, instead of meeting housing need where it exists, peripheral development creates extra societal burdens.

The intuitive response to this trend is that there is not enough land available in Dublin city to accommodate new housing, so development is forced out to the periphery. The data simply does not support this claim.

Across any metric, there is more than enough land in Dublin City to meet its housing need.

There are roughly 4,500 hectares of land zoned specifically for residential development (Z1 or Z2 zoning), said a 2018 council report. At recommended medium densities this would allow for more than 150,000 homes.

There are also 2,600 hectares of zoned land with capacity for some form of residential development.

Across all of Dublin, there is enough publicly controlled zoned land to build 58,200 dwellings.

Furthermore, there was more than 60 hectares of vacant or derelict land, spread over 282 sites between the canals in central Dublin, a 2013 council audit found.

This is leaving aside land currently devoted to large-scale surface car parking, bus depots, underused industrial estates, and military barracks in Dublin city, all of which represent an extremely inefficient use of land in the centre of a capital city and could be repurposed for housing.

In short, there is ample developable land in Dublin.

National planning policy – as laid out in “Project Ireland 2040: The National Planning Framework” – supports “compact growth” and flags this abundance of developable land in urban areas.

If land is available and national policy supports development within cities, why are there three times as many houses being built on the periphery of Dublin than in Dublin city?

The blockage is one of political economy rather than policy.

There is not one reason behind this spatial crisis, but institutional lethargy around direct delivery of housing, and a consequent overreliance on the private development finance model goes a long way to explaining the peripheral-development trend.

The private development finance model requires a profit margin of 15–20 percent on any project. This automatically makes many Dublin city sites “unviable” for delivering the housing that will meet local need.

It is easier, cheaper and a lot more profitable for developers to build on greenfield sites on the periphery of Dublin, where they have carte blanche to reproduce housing estates according to a template, rather than having to negotiate any of the complexities involved in urban sites.

Where the peripheral land is bought at agricultural-use value, securing planning permission for residential use also allows developers to increase the asset value of the land by as much as 100 times per hectare. This windfall gain is not as easy to come by in Dublin, where land is already zoned, and purchased at residential prices.

Ireland’s reliance on the private development finance model means that we are master-planning housing for our cities according to land values, rather than according to where housing is needed most.

Allied to this, the fact that co-living, hotels and luxury student accommodation provide the highest returns for land buyers, means that where private development does happen in Dublin city it tends to target these sorts of development rather than the sort that meets local housing need.

The absence of a resourced and empowered local development corporation charged with building houses on public land has led to this reliance on private development, and indeed a willingness to sell off valuable public assets where the tenure and type of housing will be dictated by “viability” and the 15–20 percent profit margin.

The Dublin Docklands Development Authority, which took over lands owned by the ESB, Bord Gáis and others and delivered thousands of homes, provides the model for what needs to be done across Dublin city.

The Land Development Agency is a step in the right direction in that it leverages public land to deliver housing, but the divisions of tenure type – even the revised 50 percent for market housing – are not ambitious enough to meet the scale of the challenge.

The specific homes that Dublin lacks are those that are accessible to people on median to lower incomes. The market is not providing these. We do not need a state body to deliver market housing. We need a state body to deliver what the market is failing to deliver: centrally located, affordable housing.