What would become of the Civic Offices on Wood Quay if the council relocates?

After The Currency reported the idea of the council moving its HQ, councillors were talking about and thinking through the pros and cons and implications.

A tradition began in East Wall of people dropping in, to share a photo to put on display – an analogue timeline in a butcher’s shop window.

Each of the seven folders holds about a hundred prints.

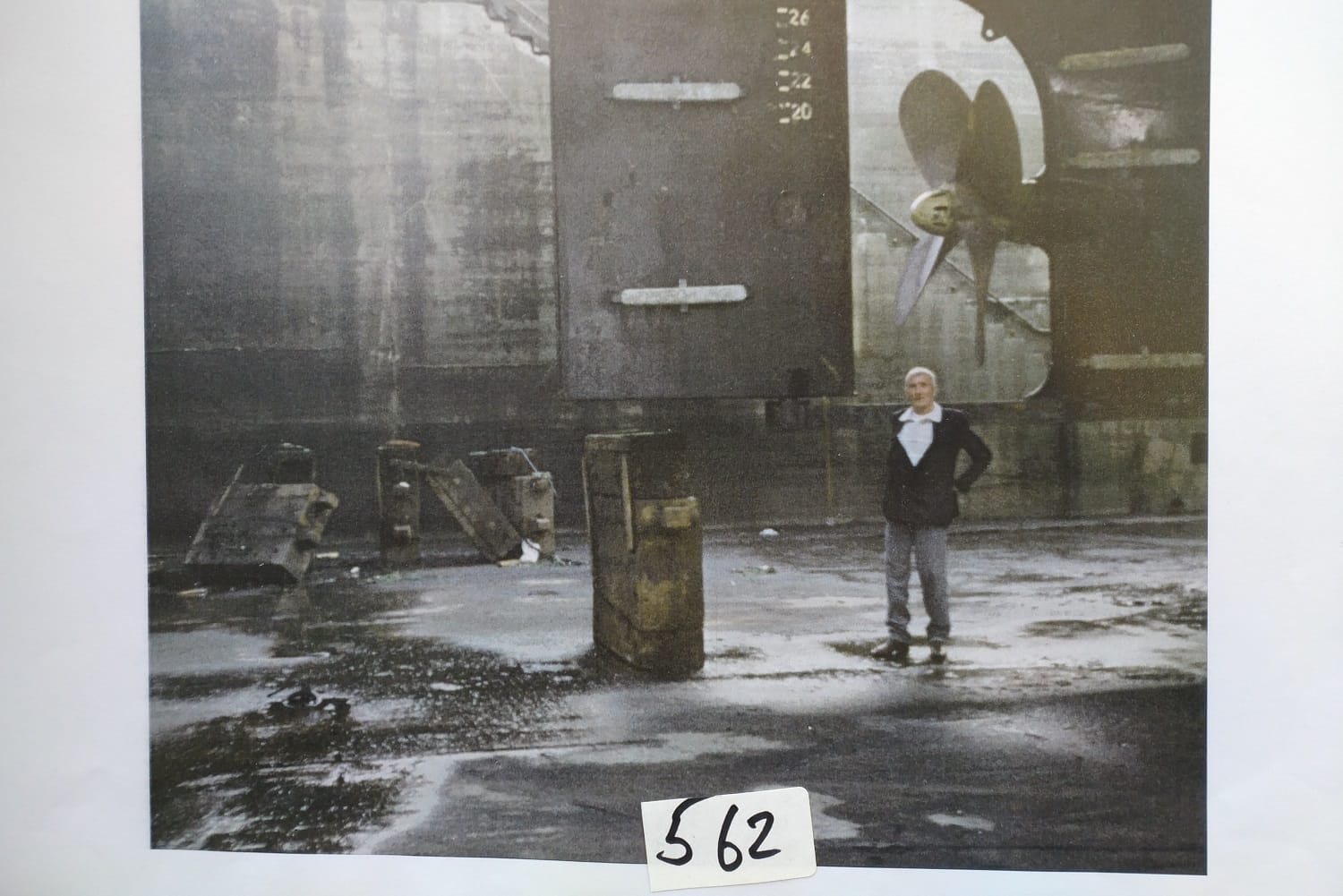

The collection began with a few photos, rescued from a skip around the corner, says Paddy Curtis, in his East Wall butchers’ shop last week.

Those early snaps once belonged to Thomas Sunderland, a local guy who worked with children in the neighbourhood. “He was brilliant. He was great with kids,” says Curtis.

Sunderland’s hobby was photography. Without him, says Curtis, there’d have been few photographs taken of the kids in the area.

Without Curtis, the photographs might have been lost. A woman on the street noticed that the photos were being thrown out and came to him. “I just took them in,” he says.

He wanted to make sure they were returned to rightful owners. Most of those photographed, says Curtis, probably would never have even seen a picture of themselves as a child.

Curtis began to display the photos in the window of Curtis Family Butchers. That way, those who might have noticed themselves as a child, or recognised a brother, sister, friend or neighbour, could get a copy.

All those original photographs from the skip are mostly gone, says Curtis. They’ve found their way back to the smiling children in their frames.

But more replaced them. A tradition began in East Wall of people dropping in, to share a photograph to put on display – an analogue timeline in a butcher’s shop window.

“We put them up there,” says Curtis. He nods to the front window of the shop, where coloured pieces of cardboard in vivid yellow, neon orange and bright red now advertise offers. The breakfast pack for €5. Five chicken fillets for the same.

He wears a red butcher’s apron with white stripes and a green collar, his butcher’s knives held in a sheath by his waist.

“People would come in and say I want two of that and I want two of that and I would write it down in a book,” says Curtis.

At the end of each week, he would visit Rehab on Parnell Street and copy the photos, charging €2 for them, and putting the money in a fund for a cancer charity.

“There was some weeks there that I could get up to a hundred photographs done, you know,” says Curtis.

It’s one of the best collections of photos of East Wall there is, says Joe Mooney of the East Wall Historical Society.

If Curtis hadn’t stashed them, “a lot of them would have been lost to the community and lost to history”, says Mooney.

It was Curtis who laid the groundwork for the East Wall History Group, says Mooney. “He’s provided an invaluable service to the community of East Wall.”

“If they hadn’t of been preserved, the story of the community and these images of times gone past and people long gone, we just wouldn’t have them,” he says.

The photos are pocket-size windows into the past. Images of an East Wall, and Sheriff Street, that is slowly disappearing, and in some cases gone.

There’s St Barnabas’ Church, which was taken down brick by brick in 1969. It had stood on Johnny Cullen’s hill for 100 years.

“It’s gone,” says Curtis, who’s worked around here for 55 years. “The gasometer, it’s gone. Jonny O’Brien’s garage is gone.”

“When you look at not just East Wall, but when you look at the entire Docklands, it’s unrecognisable to what it was, even ten years ago, nevermind 30, 40 years ago,” says Mooney.

There’s the nine stores on Church Street that one morning East Wallers woke up to find in ash on 27 June 1970, after a fire at McMahon’s Timber Yard ripped through the row.

It took five fire engines to put out the flames, newspaper reports said at the time. None of the shops were salvaged.

There’s an aerial photo of East Wall. “Just there, they’re building massive amounts,” says Curtis, pointing at it. “There’s about 12 or 14 huge cranes there.”

Curtis flicks through files of photographs, and his finger rests on an image of three young men in their twenties in Scouts gear.

“That chap that just walked past by a few minutes ago is Joe O’Reilly. These two fellas are dead,” says Curtis, before running to the door.

“Joe, hey Joe, come in here,” says Curtis. “I’m just here talking your praises.”

O’Reilly comes in for a look at the photograph.

“Isn’t he lovely,” says Curtis, “Who are the other two lads?”

O’Reilly has a think. “That’s John Mathews and Mick O’Connell.”

“Two of them are passed away,” says O’Reilly. “That was up in Larchhill I think.”

The next photo that Curtis stops at shows a communion. Thirty children squeezed together.

In the front row, right in the middle, stands a child dressed all in white like an Elvis Presley impersonator.

“This lad codded everybody,” says Curtis, and he laughs. “Because he made his communion the year before and he dressed up and he done well. I think he got more money.”

Curtis used to stick the photographs in the window, and people would drop in to boast they had better. “And I’d say, ‘Bring it into me,’” he says.

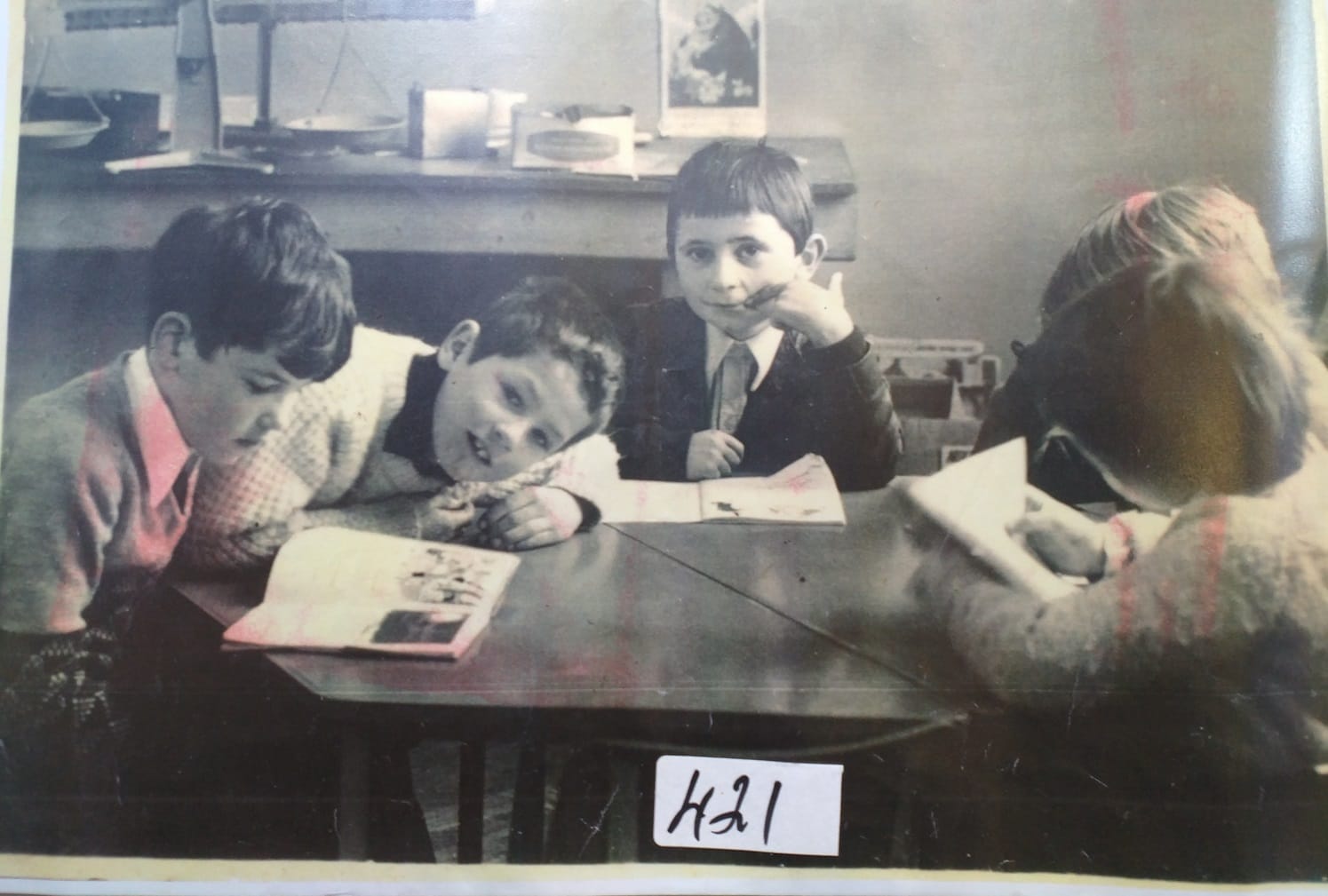

The first book that Curtis takes from underneath the shelf is filled with people in the neighbourhood. Photos of schoolchildren dating back to the 1940s. Local football teams and weddings. Nights out on the town.

“You see, it’s not everyone people would trust with a photograph,” says Curtis.

But he made sure to give them back when requested. “I’ve lost one photograph out of all the hundreds. I don’t know how I lost it. I must have given it back to one person by mistake,” says Curtis.

All sorts of photos ended up on the butcher’s window. Not everyone was happy.

Curtis shows a photograph of eight women outside the old Pigeon Club in East Wall, wearing what look like red and yellow flamenco dresses, jovially pulling up the hem.

About 20 years ago, a woman had demanded to know who gave him that one, says Curtis. Her mother was in it. She told him “she didn’t want that filth in the window”, he says.

She was fierce annoyed, says Curtis. She even wanted to sue him. “And I said it to her mother, who of course gave in the photograph. She said leave it up there another while before telling her.”

He doesn’t think she ever found out.

John Curtis, Paddy’s son, remembers about six years ago a man stopping in who’d heard about the Curtis’s photo collection on the East Wall Facebook group.

An emigrant returned on holiday, he came into the shop on the off-chance he might find a photo of himself or someone close to him, says John.

He dug through the files. There, in one, was his confirmation.

“He went straight out of the shop when he found it,” he says. “He could have gone back to America straight away.”

“He had never seen a photograph of himself as a young lad,” says Paddy.

He was well-off, a pub owner in America, Paddy remembers. “And he was so pleased to get his photograph. He couldn’t believe it. I’ve seen men actually crying when they’ve seen photographs of their brother.”

Curtis no longer displays the photos in the window. But he shares images from time to time with relatives seeking them out.

Most of them have been copied digitally and backed up on a hard drive in the Sean O’Casey Centre in East Wall, he says.

There were never enough photographs taken decades back, says Curtis. “People didn’t have cameras then.”

Some locals have told him how children would disappear from school on days when the photographer came, how they’d stay home.

“Different lads came in and told me they weren’t in them because when they knew the photographer was coming the mother wouldn’t let them go to school,” says Curtis.

Because they wouldn’t have the money to buy the photograph, he says. “Things were tight then. And they weren’t going to be embarrassed. If they didn’t go to school, nobody would be put on the spot.”

School photographs, says Mooney, might be the only group photo you’d ever be in. If you weren’t in one, there might be no photograph of you as a child.

It’s why Curtis put the photographs in the window. On the off-chance someone might find a picture of themselves, a relative, or a friend, that they never knew existed.

Everybody, says Curtis, has the right to see a photograph of themselves.