Tusla inspectors found problems with the use of physical restraint in seven children’s homes

In two cases, inspectors found that staff were using restraint to try to manage children’s behaviour, and one of those children was restrained 78 times.

Perhaps a redeveloped Dalymount Park would be the ideal home for a museum dedicated to the story of Irish football, encompassing everything from Harold Sloan to the Drums.

Redeveloping Dalymount Park, if that goes ahead as planned, would transform the iconic football stadium. But nothing could alter its spirit and sense of history.

Since September 1901, Dalymount has been at the heart of Irish football, home to Bohemian FC, but hosting many other clubs during its lifespan. It’s a testament to the current revival of both the club and the league that this season has witnessed capacity crowds.

The opening of Dalymount Park had all the hallmarks of a big occasion in Dublin. The Lord Mayor of Dublin did the honours. The Royal Irish Constabulary band reportedly “played a beautiful selection of music before the start, and in this alone the spectators got good value for their money”.

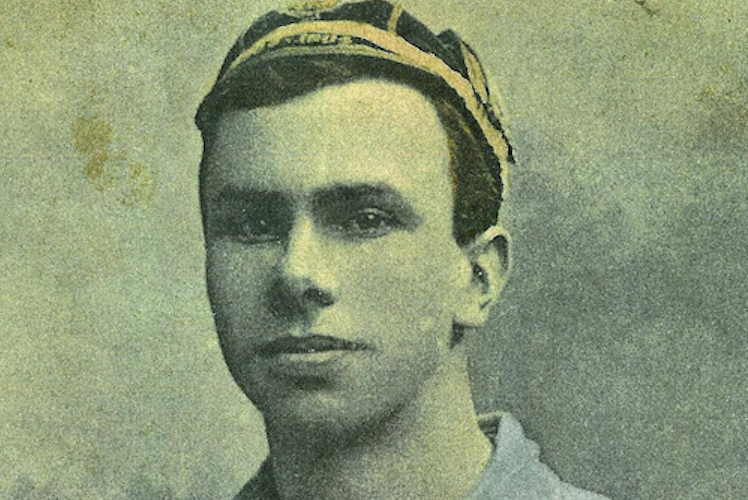

Bohs won the day 4-2, with the first goal in the new stadium scored by Harold Sloan. Sloan would be killed in action on 22 January 1917, one of many brilliant sporting talents cut down by the horror of the First World War.

The stadium of humble wooden stands of the early twentieth century was far removed from the Dalymount we know today. Still, the venue quickly became the primary soccer stadium in the city, and by 1904 it hosted its first international clash, as Ireland and Scotland faced off.

At a time when Irish football was dominated by Belfast teams and a northern administration, packed crowds at Dalymount Park were a reminder of Dublin’s commitment to the game.

The primary footballing sides in the capital then were Bohemian FC and Shelbourne FC, which are now destined to share Dalymount.

Todd Andrews, a leading participant in the Irish revolution, recalled in his memoir Dublin Made Me that the supporters and players of the game were almost “exclusively of the lower middle and working classes”. In reality, football had a broader appeal than this.

The famed football architect Archibald Leitch – who drew up plans for many of the celebrated footballing grounds on the neighbouring island, including Ibrox, Anfield, and Villa Park – would transform the stadium further in the early 1930s.

Bohs historian Ciaran Priestley notes that “Dalymount was a modest example of the classic British stadium design of this era in which social ethnology was incorporated into the layout of the ground; it featured banks of open terraces to accommodate the working classes while directors and middle-class spectators were annexed in the expensive seats.”

Much of the aesthetic value of Leitch’s stadiums has been lost to ground modernisation in the UK, especially in light of the move to all-seater stadiums. Dalymount, even today, retains the feel of another time entirely.

Eoin Hand, the footballer-turned-commentator, has said that “Dalymount was one of those old-style, claustrophobic noise-boxes where the fans were crammed right up against the pitch.”

Dublin memoirs, an ever-growing body of literature, are packed with references to Dalymount Park.

In The Rocky Road, Eamon Dunphy writes of the clash between Shamrock Rovers and Manchester United in 1957. A legendary United team, spearheaded by manager Matt Busby and including Cabra native Liam Whelan, packed Dubliners into the ground.

“They burst with graceful purpose onto the Dalymount pitch to a welcoming roar of acclaim. Respectful, almost reverent, no sense of the partisanship that usually attended when visitors took the field. Most had come to pay homage,” it reads.

Not all games at Dalymount were such straight-forward affairs. The visit of Yugoslavia in 1955 to play Ireland in Phibsboro drew clerical condemnation, with Archbishop John Charles McQuaid encouraging Catholics to boycott the fixture.

Despite McQuaid’s calls, and a significant picket by members of the Legion of Mary holding anti-communist placards, more than 21,000 football fans turned up. Minister for Defence Oscar Traynor, a football aficionado, attended the game, while the veteran republican Dan Breen was so infuriated by clerical condemnation of a football match that he left his bed in a nearby hospital to go watch, and thus “strike his last blow for Ireland”.

The significant turnout at Dalymount, despite the clerics, is a notable example of the Irish public ignoring the dictums of McQuaid and his ilk. One of those who lined up for Ireland that day, Liam Tuohy, would later remember watching the Yugoslav players bless themselves in the tunnel before the game, feeling that “there were nearly more Catholics on their side than there were on ours”.

Beyond football, the social history of the ground has included numerous musical festivals and concerts. Most famously, Bob Marley played there in July 1980. The inimitable Pat Egan booked some unforgettable line-ups at the venue, including Meat Loaf supported by poet John Cooper Clarke.

More forgotten is Sunstroke, an attempt to establish an annual grunge-focused festival in the early 1990s. Bringing Sonic Youth and Faith No More to Phibsboro, the noise level was a little much for local residents, and the festival was moved to the RDS.

No other football pitch in Dublin has been graced by both Zinedine Zidane and Brendan Behan (a participant in a charity kickabout in the 1950s). Moving forwards, it is hoped that any “new” Dalymount Park can sustain the magic of the old.

The planned renovation would see Bohs groundsharing with Shelbourne FC at Tolka Park in 2021 and 2022, before both teams move into the newly redeveloped ground the following year.

Tolka Park, with its own magnificent sporting history stretching back to the glory days of the iconic Drumcondra FC (“the Drums” to generations of Dubliners) will be a sad loss to football in Dublin.

Perhaps a redeveloped Dalymount Park could be the ideal home for a museum dedicated to the story of Irish football, encompassing all from Harold Sloan to the Drums.